ConnCAT | Culture & Community | Dixwell | NXTHVN | Arts & Culture | Newhallville | Visual Arts | Arts & Anti-racism

Mitchell Rembert with the in-progress carving of his parents. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The two figures lean into each other, hands clasped. Even in the not-yet-done-ness of the leather, there's a sweet intimacy there, so tender that it radiates off the surface. There is Winfred, his face not yet weathered by time. And Patsy beside him, her eyes bright with that wild promise of a life together. A frosted piece of cake passes gently from her hand to his mouth, and a viewer can almost taste it.

The image, from New Haven artist Mitchell Rembert, is a portrait of his father and mother on their wedding day in 1974. This winter, it’s just one of the ways that his dad, the late artist Winfred Rembert, has continued to give back to New Haven since his passing in March 2021. For his children, wife and the growing community that loved him, it is a reminder that his generous spirit is still here.

Rembert died last year at 75 years old; read more about his exceptional life here, here, and here. A full section on Mitchell’s work, which is carrying on the craft, is below.

“No one can take this away from him,” said his daughter Lillian, who is named after the woman who raised him. “He is part of history. Not just my history—I have to share my father with everyone. And now, it’s not just with siblings. It looks like it’s gonna be with the world.”

Patsy Rembert at a discussion hosted by the Yale Justice Collaboratory at NXTHVN last month. Erin Kelly is to her left; the historian Elizabeth Hinton is to her right. Lucy Gellman Photos.

In his absence, Rembert’s laughter-infused footprint has continued to grow. His memoir Chasing Me To My Grave, as told to the philosopher and Tufts University professor Erin Kelly, was published last year and received the Pulitzer Prize for biography in May. Since, there have been suggestions from Site Projects New Haven that it is well past time for a Rembert mural in the neighborhood where he spent the last decades of his life. Last month, the Yale Justice Collaboratory looked to his work as a template for carceral reform, abolition, and restorative justice.

“It is unreal,” Patsy Rembert said in an interview last month, at the Yale Justice Collaboratory’s gathering at NXTHVN on Henry Street. “I didn’t expect this kind of love for my husband and I am just so proud at this moment.”

“He was a significant part of my life, and him not being there has not been easy,” she added. “Not because he didn’t leave things okay for me, but the presence of him. I’m gonna tell you, I didn’t want to go on. I wanted to just lay down and go to sleep. It’s hard to describe the absence of him. Just being in my home, being together, it means so much to me.”

A Generous Spirit Lives On

The panel at NXTHVN last month.

At a panel of the Yale Justice Collaboratory at NXTHVN last month, Kelly said that she regrets that Rembert did not live to see publication of the memoir in the fall of last year, but is grateful that it is helping spread his story. Before he passed, Rembert read and approved a copy of the completed manuscript, and "he was very happy with the way it turned out," she said.

Rembert's story begins in the Jim Crow South and ends in a home on Newhall Street, where he and his wife Patsy lovingly nurtured their family of eight children. Born in 1945 in Americus, Georgia, Rembert grew up in the care of his aunt Lillian, who he referred to as "Mama" and after whom his daughter Lillian is named. At just three months old, he entered her home, where she raised him as her son. That moment, in which his birth mother delivers him into Lillian’s arms, is commemorated in The Beginning.

Many of his works take a viewer back to his childhood, showing the immense protection and cover that, even and especially in the segregated South, Lillian sought to provide. In On Mama's Cotton Sack, for instance, a viewer can spot baby Winfred riding on the back of her cotton sack as she works in the fields. There’s an alarming beauty and world-weary routine-ness to it all at once, a reminder to the viewer that this is a matter of survival.

One of Rembert's many scenes from church. In New Haven, he and Patsy worshipped at First Calvary Baptist Church on Dixwell Avenue, where his funeral was held last year.

Or in Flour Bread, where Rembert shows the sacrifice Lillian—who was allergic to flour dust—would make in baking for him as a child. In the image, done in 1998 (he returned to it in 2003, where he is pictured in the image), Lillian stirs ingredients in a bowl, a bag of flour, cake of shortening, and bowl of eggs and scalloped baking dish in front of her. That protective, warm energy exudes from works from this period in his life, from The Beginning to What’s Wrong With Little Winfred?

But Lillian, whose home was on the edge of a cotton field, could not shield him from the realities of segregation and the weight of white supremacy. As a teenager, Rembert fled the cotton fields to Hamilton Avenue, a self-sustaining Black business district in Cuthbert, Georgia. There, "he discovered all these Black establishments—pool halls, juke joints, shoeshine parlors, and a lot of life there," Kelly said.

Years later, the neighborhood and its businesses would spring to life anew in his pieces, dozens of which celebrate the imprint that Hamilton Avenue left on his mind and his heart. As she spoke at NXTHVN, Kelly pulled up images of Jeff’s Cafe and Pool Room, where Rembert spent some of his most formative years.

"He loved it there. These were really cherished memories," Kelly said. It was also an civic space that would change his life.

In the early 1960s, it was through a job at Jeff’s Cafe that Rembert learned about nonviolent protest and the civil rights movement, including a demonstration in nearby Americus that changed the course of his life. During the 1960s, Rembert was fleeing violent white counter-protesters in Americus when he spotted a car, keys dangling from the ignition, and jumped in it, desperate to escape. It led to his arrest in Cuthbert and decades in the carceral system, including years on a chain gang a near-lynching from a white mob.

Winfred Rembert, Jr. and Lillian at NXTHVN.

Some of his most powerful work comes from that period of his life, asking a viewer to bear witness and to learn from the pieces. From the 1980s through his death last year, Rembert returned to the image of cotton fields and the chain gang to show the immense cruelty of segregation and the continued economic deprivation of Black people in America. At NXTHVN last month, Patsy Rembert pointed to the images Cain't To Cain't and Pregnant In The Cotton Field as just two of those examples.

In the first, Rembert shows dozens of Black bodies bodies bent over cotton in Georgia’s hot, humid fields, a white foam of raw cotton emerging from the baskets on their backs. Thick green grass and specks of red Georgia soil peek through. At the lower left, a white overseer cuts through on a dappled horse, a striking reminder of the force and cruelty always present in the fields.

Like so many of his works, It draws in a viewer with vivid, intricate design and bright color, and then reveals its complexity figure by figure as one gets close to the canvas. Even as an overseer marches his horse through the fields, it's possible to be taken by the haunting beauty of the cotton and the vibrating greens of the grass around it.

So too in the second, in which he has depicted a heavily pregnant woman crying out, her eyes closed as her hands rest on her belly. Behind her, a fellow worker from the fields holds her shoulders, eyes closed as if in prayer. As she looked to the image last month, Patsy explained that it was not uncommon for white overseers to expect Black women to give birth in the fields, and then continue working.

Mothers, their bodies still a shock of pain, would lay their newborn babies close to dogs, who would make sure snakes didn’t get to them.

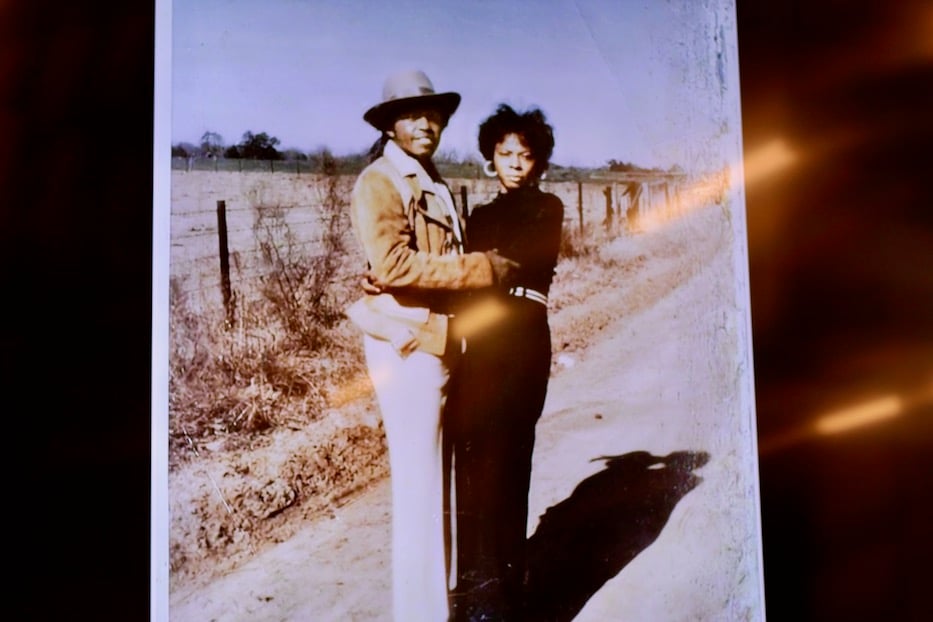

A young Winfred and Patsy Rembert. After Rembert began writing to her (she was then Patsy Gammage) from prison in 1970, she told her family that he was the man she was going to marry. The two married in 1974.

And yet even in the frustration of those years, Patsy Rembert said, his story was and is one of incredible resilience. Rembert often had a sense of humor around him: he was big hearted and loved a good prank. In pieces like Doll's Head Baseball, the artist conjures the memory of the eponymous game, in which Black people named dolls' heads after the white people under whom they were forced to work. They would play the game as white people watched, totally unaware.

In celebrating Rembert's memory during the recent discussion at NXTHVN, Kelly focused on the tremendous and moving impact of his art. Several years ago, she came upon his piece All Me while engaged in her own research on the ethics of the prison industrial complex and the American carceral state. She was moved by the image, which shows dozens of people dressed in the black and white stripes of a chain gang, some lifting heavy, weighted mallets as others bring them down.

"All of those pictures that you see are him," Patsy Rembert said. "He felt like that's what he had to do in a day in order to survive on a chain gang. And he tried to fit whatever situation he was being put in in order to maintain some kind of sense of self while he was in prison."

After she saw it, Kelly couldn’t let the image go. Seven years ago, she and Rembert had their first meeting at McBlain Books in Hamden. They began to map out a biography, and didn’t stop talking until Rembert passed away, Kelly said. In between were many visits to the Rembert home, where his art adorns the walls in every direction. She is now, like many of Rembert’s close friends before her, effectively a member of the extended family.

Historian Elizabeth Hinton, Yale School of Art Dean Kymberly Pinder, and poet, public defender, Freedom Reads Founder and 2021 MacArthur Fellow Reginald Dwayne Betts.

Since the publication, the book has become a powerful and necessary social history, said Yale historian and professor Elizabeth Hinton. She stressed that the book should be required reading for not just history students of all ages, but all Americans. She pointed to Pregnant in the Cotton Fields, Rembert’s recollection of women giving birth in the cotton fields and then going right back to work, because they had no other choice.

“Reading Winfred’s book and his art capture things about U.S. history and capture things about Black history that an archive never could,” she said. “I really look at it as one of the best social histories of Jim Crow that exists. I was pretty astonished when I read it, and I think it should be required reading for everyone in this country.”

“It really shows the lived experience of white terrorism and supremacy,” she added.

Kymberly Pinder, who was named dean of the Yale School of Art in June of 2021, said that she finds the images incredibly evocative. Born and raised in Baltimore, Pinder grew up hearing stories of the South, which both of her parents fled in their youth. Rembert's work helped her understand the danger of the American South that they were living in, and the way white supremacy meant that they were never truly safe.

Patsy Rembert with Site Projects Member David Sepulveda. Sepulveda has been one of the people advocating for a Winfred Rembert mural in Newhallville, where he spent much of his New Haven chapter.

When she saw Rembert's work Almost Me, a memory of the near-lynching that would stay with him for his life, she remembered her father telling her that when he punched a white boy who had spit on him, "that was his ticket out of the South." She let the whole meaning of that phrase sink in anew.

"Seeing these images, it was as if I was seeing what they were always trying to envision for me in those stories," she said. "It made me appreciate where I was in time, and what they had left in the South, escaped."

"The sharing is one of the most important things that we get from here," she continued. "The incredible generosity that is in this book. Like, yes, artists can do pictures to tell their story, but also to have this amazing and incredibly poetic narrative about his life is something that not everyone does share."

During the Collaboratory's discussion at NXTHVN last month, many of the panelists also pointed to Rembert's work as a powerful and compelling argument for restorative justice. Speaking midway through the evening, poet, public defender, 2021 MacArthur Fellow and Freedom Reads Founder Reginald Dwayne Betts noted how moved he was by Rembert’s story.

“The best of writers, I think, are able to make you remember that it is a commonality to your experience, to their experience,” he said. “No matter if you share the same race, no matter if you share the same gender, no matter if you share the same culture.”

He praised the late artist for his ability to show the horrific beauty of cotton growing in the fields, a reminder “of the necessity to hold the sorrow with the light,” Betts said.

“I hope that you all get this book, read it, and take away from it an understanding of togetherness—that we need to talk to one another,” Patsy Rembert said. “We can't undo what's been done, but we can make sure it doesn't happen again.”

Passing On His Craft

Mitchell Rembert with a picture of his parents on their wedding day.

For Mitchell Rembert, who is carrying on his father's craft at 38, this fall marks a full-circle moment. After learning to do the carved, tooled and dyed leather designs that fill his family's Newhall Street home, he is passing it on to a future generation as a teacher at the Connecticut Center for Arts & Technology (ConnCAT). Since the summer, he has been teaching students in the organization’s after-school program. He currently instructs 42 students over multiple sections.

He wishes his father were alive to see it.

"I'm not there yet, but I'm good enough to put down what I have to for the moment," he said on a recent Monday at ConnCAT, in the classroom where he teaches three days a week. "I'm good enough to carry on the torch. I want people to see my skill grow over time. My messages get deeper overtime."

It is a craft that follows a childhood spent in New Haven, under the watchful eye of his parents and seven siblings. As a middle child, "I did whatever I could to stand out," he recalled. Born and raised in New Haven, he attended the now-shuttered Timothy Dwight School, and later Augusta Lewis Troup School, Sound School, and Riverside Academy.

Around him, the Rembert home was never quiet: a basement playroom boasted sets of legos and animated figures that the kids would play with together. What they lacked in material resources, Mitchell said, his parents made up for in the doting care of their children.

He didn't realize that art was calling him for decades, he said, until suddenly he did.

Mitchell Rembert at NXTHVN last month.

Growing up in New Haven, "race became a big thing on my radar" long before art, he said. If he so much as opened the door, New Haven instantly reminded him of what it meant to live in a city where de facto segregation was still alive and well. At home, his father didn't speak often about his past, but Mitchell could see it in works that sprang up around the house, from sprawling cotton fields and portraits of carceral life to sweet celebrations of his and Patsy's love.

"Being young and rebellious, I felt like I was choosing between success and my Blackness," he said. "I failed a lot. There was no one thing I was into. As soon as something didn't work out, I moved on to the next."

It took decades for Rembert to come to leatherwork. After high school, he trained as an emergency medical technician (EMT), then worked a string of jobs jobs in retail, then as a school security guard and auto mechanic. From New Haven, he moved to East Haven and West Haven, working multiple jobs to make ends meet after his daughter was born. Almost 10 years ago, his financial difficulties led him back to the home on Newhall Street, where he asked his father for help.

The senior Rembert ruminated on it. Then on his birthday, Mitchell recalled, he offered his son something money couldn't buy.

Mitchell Rembert's first work. Image contributed by the artist.

"He says, 'I'm gonna give you the greatest gift I can give any of my children at this point in time,'" he recalled. "He gives me a bag, and it's leather and tools. I got what he was saying, but I wanted money and help, and I kind of turned my nose at it initially. At that time, I couldn't really see the bigger picture."

He gave it time. So did his father. As Mitchell accompanied his dad to exhibitions around New Haven and in New York, he sometimes found himself speaking about his father's craft. As his dad’s mobility slowed down, he spoke about the work more and more frequently, he said. It made him realize how proud he was to have the craft in his family—and how deeply he wanted to take it on. He was talking about his father's work at an art fair in Lower Manhattan when something clicked.

"It was like a message that I was meant to be here," he said. "I came to this realization that my father had been training me my whole life to do this. So I went to it, you know?"

At first, Mitchell was so displeased with the quality of his work that he nearly quit. He would try to tool the leather, and it would crack and flake at his fingertips. It was his brother Edgar, who later passed away, who encouraged him to keep going—and to ask for assistance. Mitchell finally did.

When the elder Rembert looked over his son's canvas, he knew immediately what was wrong. He told Mitchell to hold the carving tool straight upright, instead of at an angle. He taught him to bear down and make deep marks, instead of treating the leather like something delicate and breakable. It wasn't how leather carving was taught elsewhere, but that didn't matter, Mitchell said. It was the Rembert legacy.

In his first finished piece, a cotton field sprawls out in front of the viewer, thick green grasses between the rows. In the foreground and the background, Black bodies lean over the white balls of cotton—except they are picking sneakers that have grown from the dirt. It is inspired partly by Mitchell’s first job at a Foot Locker, during which he realized how little money people make in retail, and in part by his father's style. He completed it in his parents' Newhall Street home.

"I was like, I might as well have been picking cotton," he said of the piece. "One day, I looked at it and I saw it in a dream—a bunch of kids just picking sneakers."

After he had finished the first work, "I went crazy after that," he recalled. He began salvaging even the smallest piece of craft leather, experimenting as he tooled. From his dad, he learned to shop at Tandy Leather, now the only remaining brick-and-mortar leather outlet in the state. He learned to sketch on the leather, cut into the drawing, wet the surface and then bevel it. Only after the first design is done does he begin the dyeing and painting process.

He is now working on a piece based on a photograph that hangs in his mother's home, of his parents on their wedding day. He said that he plans to make multiple versions—one in traditional black and white, true to the mood of the photo, and another in brilliant color.

His work is still growing, he added. Earlier this year, a grant from the city's Creative Workforce Initiative meant that he could afford enough leather and swivel knives for his students at ConnCAT. He is also a recipient of an Artists Corps grant, funding from the National Endowment for the Arts that was redistributed through the Arts Council of Greater New Haven earlier this year.

"I just want people to see the opportunities my dad gave me," he said. "How he tried to give ... he did his best to give us a different life."

“He’s Somebody”

Lillian Rembert with U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro and her mother, Patsy Rembert, at a discussion at NXTHVN last month. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Lillian Rembert, the eldest daughter in the Rembert family, echoed that love for her father in a discussion last month, before the panel discussion at NXTHVN. In October, she learned that her father had posthumously won a Pulitzer Prize while on her route as a postal carrier, which takes her through the Newhallville neighborhood that raised her. For an hour, she had been turning off her phone as dozens of calls came through. Then she turned it back on.

"I thought, I can't believe it," she said. "The guy keeps winning. And just a flood of emotions, a flood of memories. We grew up very poor—fishing at the creek for food, making our own biscuits, our own homemade syrup. So the idea that this man that always said, 'I'm gonna make it, and you'll see' ... for that to happen, no one can take this away from him."

She added that she thinks of every step she takes as part of a growing, evolving Rembert legacy. During her father's life, she heard hundreds of stories of his aunt Lillian, who raised him like a mother. She knew she was named after a woman who could do anything. Now, she thinks of the way he also lives on through her.

When something breaks down around the house, she still thinks of what her father would advise her to do ("sometimes I don't get the answer I want, but it is always the answer I need," she said with a smile.) When her furnace went cold a few months ago, she remembered how he would put sheets on all of the doors and windows, and try to keep one room warmer than the others. In that way, she said, he may have left, but he is still close.

"He's somebody," she said. "My father is somebody."

Learn more about Chasing Me To My Grave here. This Saturday, the Urban Life Book Discussion Series will discuss the book from noon to 1:30 p.m. at Wilson Library. Learn more here.