Books | Culture & Community | Institute Library | Arts & Culture

Readers Saturday. Miranda Jeyaretnam Photos.

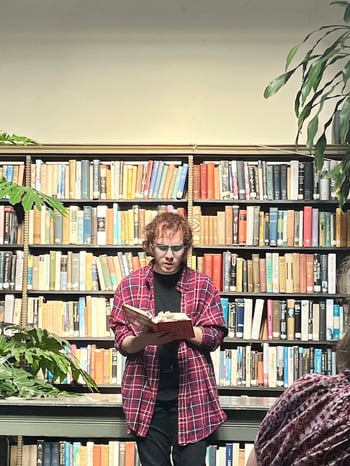

“Is there anything that periods don’t take over and control?” Piper Zschack asked, standing in front of a backdrop of books.

Zschack, a 2022 graduate of Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School, was reading aloud from his entry in Our Red Book, a compilation of 67 essays edited by Rachel Kauder Nalebuff about people’s first periods. Last Saturday, the story joined several others at the Institute Library, where Nalebuff and readers held an intimate launch party among the building’s shelves. Roughly 30 people attended.

The book was released this month from Simon & Schuster; it is available at Possible Futures bookspace and online. New Haven-based contributors include Zschack, Mindi Rose Englart and her daughter Lily Sutton, immigrant rights activist Kica Matos, Co-Op grad Nadia Gaskins, Nalebuff’s mother and former Artspace New Haven Director Helen Kauder and many others.

“Eventually, after hearing enough stories about bleeding, you start to see the world differently,” Nalebuff said at the reading. “For every moment in history, someone is getting their first period—during the first landing on the moon, during the fall of the Berlin Wall, at that exact moment there is someone who has that story. In other words, it's happening all the time."

Editor Rachel Kauder Nalebuff with contributor Sofiya Moore.

Saturday, she began with her own story, the first entry in Our Red Book. Her first period came during a visit to her widowed grandfather, and the memory is filled with loneliness. In the essay, she recalls crying in her grandfather’s bathroom, unsure of how to navigate the world of menstrual hygiene with little adult guidance, let alone any comfort.

After the announcement of Nalebuff’s first period, her great-aunt, Tante Nina, shared the harrowing story of how she got her first period while fleeing Poland during the Holocaust. From there, Nalebuff strung together the stories of the rest of her aunts and her mother, which open the book.

She heard several new stories from her family along the way. Her aunt Nina Kauder, the “Little Aunt Nina” named after Tante Nina, had her first period the same year that her mother passed away.

It was not ritualized in the way it so often is, Nina said Saturday. Instead, she found answers through snooping around her older sister’s room, stealing tampons and borrowing her copies of Our Bodies, Ourselves and Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. There were some things she could not figure out alone though, like the color of her period.

“Nowhere did I read it could be brown, it could be thick, it could be thin, it could be ropy,” she read. At the bottom of her essay, which is written like a letter to Nalebuff, she inscribed for this reporter: “Every drop counts!”

“I didn't think that I had a story,” she said in an interview afterward. “It was only through talking with Rachel that she gave me a very different perspective on it … Not only is there so much shame built in, but there's also just so much repression built in, that … thinking that I didn't have a story was part of that story.”

From those intimate stories shared between family members to the words of author Judy Blume, whose young adult books helped many young readers through the experience of puberty, each essay brought out different perspectives.

From those intimate stories shared between family members to the words of author Judy Blume, whose young adult books helped many young readers through the experience of puberty, each essay brought out different perspectives.

For some of Saturday’s readers, memories of first periods were filled with anger and discomfort.

Zschack, who came out as trans during high school, pointed to getting his first period as a dysmorphic experience familiar to many trans individuals going through puberty. “The trauma of being repeatedly reminded that your body, both inside and out, does not belong to you and is not under your control isn’t something that just resolves itself,” he read from the essay.

Zschack's story spoke to the larger space that menstruation occupies in the cultural imaginary. Periods are stigmatized and turned into moments of shame, or otherwise they are celebrated. People congratulate you, regardless of how you individually feel about getting your period. He deconstructed that space: periods can just be something that happen or happened.

“Bleeding doesn’t always make you more compassionate or intelligent or self-aware,” he read. “Sometimes it just makes you suffer.”

For other readers, a first period was a moment of celebration. Lily Grace Sutton, a junior at New Haven’s Sound School, told a story of how she bakes red velvet cakes for each of her friends when they get their first period.

“I make period cakes simply because no one else will,” she writes in her essay.

Sutton's story echoed an experience that resounds throughout the book: a lack of comprehensive sexual education, be it from school, home or the outside world. In her essay, she encapsulates the misinformation and often trivialization of what it is like to menstruate. She included the fact that her school showed a video about periods—instead of holding a discussion—that claimed people on their periods did not feel pain.

Her mother Mindi Rose Englart, an author who until this year taught creative writing at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School in New Haven, is also featured in the book. Englart writes about how she began menopause as her daughter started her period. Many of the stories in the collection contain the mother as a figure that guides and protects—or at times fails to do so. It was particularly moving to see both mother and daughter’s stories in the same section, a cyclical image of growing up.

“Had any of my teachers ever talked to me about a person's experience of menstruation?” Nalebuff wrote about the essay. “When I think about how challenging it is to grow and to grow into a changing body, it seems striking that no adult ever said to me, ‘Listen, I went through this, too’ or ‘I'm going through a version of it now’ or even just ‘Change is constant, honey.’”

The book itself functions as a kind of teacher or guide, even if it does not offer explicit advice. It also has a political function: Nalebuff weaves together the personal with advocacy, through the inclusion of interviews with reproductive rights activists and writing by community organizers like Somáh Haaland, a queer Indigenous artist.

“That story of your first period, like can stick with you in such a intense way,” Haaland, who is from New Mexico and currently lives in New York City, said in an interview.

Nalebuff said that many of the stories offer the reader a window into many different forms of injustice and oppression, particularly because of the stigma surrounding menstruation. The period itself is only one element of the book — what these stories reveal are the ways that racism, poverty, incarceration and other forms of injustice work in tandem with the shame imposed on our bodies.

The book includes several stories from incarcerated women, who describe being intentionally deprived of sanitary products or being surveilled while changing. These stories demonstrate the extent of patriarchal control in the most visceral way.

“There's something very circular about this book and how it keeps taking me back to some of the same themes and some of the same places,” Nalebuff said. “I end up back home, but I'm in a very different place than I was when I was a teenager — and New Haven is in a different place and the young people in New Haven are in a very different place than when I was growing up. So you can really feel that shift, because you have this direct comparison over the course of 20 years.”