Boricua pride | Arts & Culture | Yale University | Movimiento Cultural Afro-Continental

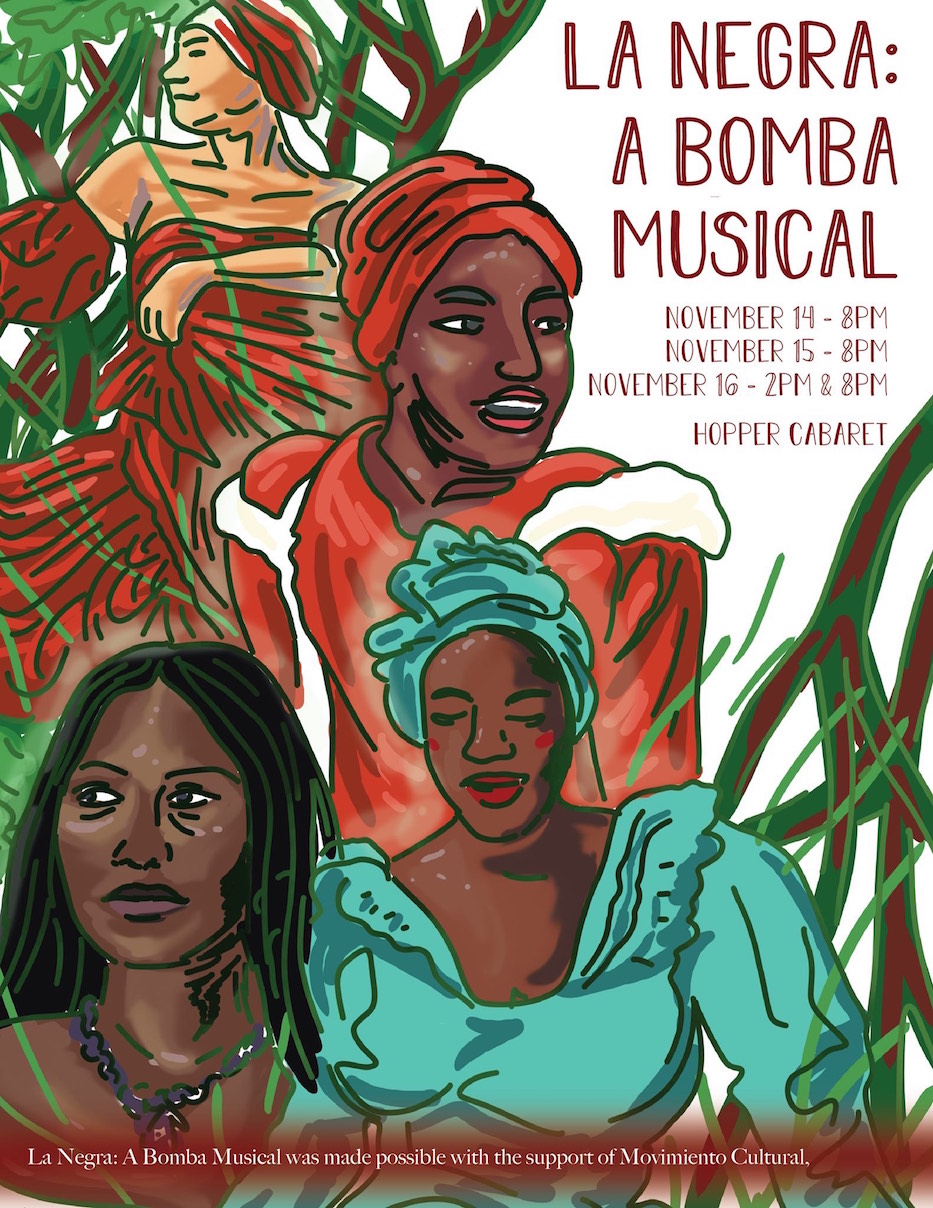

| Photo credit La Negra. |

A woman stands at center stage, eyes blazing. Her feet, planted firmly in the ground, hold centuries of history and rebellion. This is Yuisa, the first female Taíno chieftain, opening herself to centuries of pain that are about to descend on the island. She opens her mouth, and her voice is strong and winding as the mangroves she’s been tending to.

“My sons, you haven’t been honoring your daughters,” she says, wrapping the space in sound. “Where are your birth mothers, huh? Are they on their feet? And your wives? Are they hiding your Medallas? When my daughters are unhappy, I till the earth so we can start again.”

Yuisa (Addys Maria Castillo) builds the backbone of La Negra: A Bomba Musical, running at Yale’s Hopper Cabaret now through Saturday night. Written and directed by Yale University junior Saphia Suarez and produced by students Camara Aaron and Gianna Baez, it brings together students, community members, and musicians and dancers from the local group Movimiento Cultural Afro-Continental for an 80-minute tour de force in dance, song, history, reclamation and trauma.

Tickets and more information for the show, which may have a New Haven encore next year, are available here.

Bomba is a communicative dance form that spread during the Afro-Caribbean slave trade, during which Loíza became a major hub because of its harbor. Through a system of call and response, dancers "talk" to drummers and percussionists without ever having to use words, moving their bodies, feet and their long, ruffled white skirts, hats, and wrapped hair as a form of speech.

It is a healing form, rallying cry, and old-school messaging network of both release and revolt, so clear in lyrics like “Cada día sufriendo más/si no bailo esta bomba, me voy a morir” (“Every day I’m suffering more/If I don’t dance this bomba, I’m going to die”).

“I really wanted to tell a story that existed in the batey, in the dance circle,” Suarez said in a phone call Thursday afternoon, before a packed opening performance. “I wanted to see how you could play with storytelling in that space.”

In La Negra, she has achieved it, unspooling a history (really, a herstory) in four parts with vibrant dance, full-lunged song, lush harmonies and propulsive drumming that drives the batey just as the batey drives it. Set in chronological order, the work opens on the female Taíno Chieftain Yuisa, scorned by many of her own people after forming a relationship with sixteenth-century conquistador Pedro Mejías in a move to spare many on the island from impending slavery.

Suarez writes it beautifully, letting Yuisa tell a story that history has largely taken from her, or forgotten entirely. As “El Conde de Loiza” rises around her, dancers flooding the stage, she speaks with absolute certainty, confirming that the joke is on him: “You don’t become the first woman chieftain on the island without learning the game of men.”

“I am the drum and the man thought he was the master,” she continues. “But he does not know my beat so I win every time.”

Suarez has set a tempo that comes straight from her wildly beating heart, and keeps going. From Yuisa, the work transitions seamlessly to La Negra Martina (Amira Williams), who orchestrated slave escapes through bomba, dancing fellow Puerto Ricans to freedom “right under slave owners’ noses,” Suarez said. It fast forwards to Adolfina Villanueva Osorio (Cleopatra Mavhunga), who was killed by Puerto Rican police officers in front of her children in the 1980s, when she refused to leave her land.

In a final portion set in the present, Suarez weaves the story of Hurricane María with that of the Colectiva Feminista en Construcción, a grassroots feminist organization that has advocated for years around stronger educational and social programs for women on the island. As women knead tasteless, pale dough they exchange stories that open a kind of post-María whisper network, in which whole centuries of violence are still being repeated.

A through line of resistance runs through each, bodies constantly in motion as women find themselves embedded in history. But it feels less like a history lesson and more like a bright, spot , a void that's filled so loudly and so quickly one’s heart might explode. At an opening night performance Thursday, some audience members silently mouthed the words from their chairs. Attendees clapped and rocked in their chairs. Others started to cry halfway through and then didn’t stop.

In some ways, La Negra has been years in the making. Raised in Boston, Suarez has bomba literally in her blood: members of her family hail from Loíza, and she’s seen the dance performed many times, almost always outside in the dirt of somebody’s yard. By the time she got to Yale, “I was interested in telling stories that reflected me,” including a play on the Movement For Black Lives that she produced her senior year of high school.

But when she started writing, it wasn’t clear to her what exactly the script for La Negra wanted to be.

“It went through many different drafts in the beginning,” she said. “It was an old love story. Then it was tied to my family.” But it never felt quite right.

This February, she brought together members of Despierta Boricua at Yale and the Yale Black Women’s Coalition for a bomba workshop led by Movimiento Cultural. It was the first time she had met the group, which performs bomba in New Haven and also teaches each week at the Blatchley Avenue Police Substation in Fair Haven. She recalled standing in the workshop, held inside a university building, and starting to cry because she had never seen it performed in an institutional context before.

“I'd only seen bomba performed in a dirt front yard,” she said. “And I realized it could be another piece of home that I brought into this space.”

Last summer, Suarez was able to travel to Puerto Rico, where she spent time speaking to the artist and oral historian Samuel Lind. In his histories, she found the voice of the show: four women who stretched from the sixteenth century to the present, proposing a better way forward with every footfall. When she returned and continued working on the musical, she brought performers back to Movimiento Cultural to work with the group.

Suarez has soared this respect: La Negra shows that, as one character says, “the power of bomba is to be whole. To be human. To be free.” As dancers fill the stage, they bind Afro-Boricua storytelling, histories of diaspora, women’s liberation and Yale’s own past and present. There’s almost no set and intimate lighting, but a series of projections do the trick, particularly moving as they enter very recent territory with footage from the “Ricky Renuncia” protests that filled the streets earlier this year.

Suarez has also done her research: the pumping heart of this show is Loíza, but it is also New Haven. La Negra has no soul without Castillo, and little sound without Kevin Diaz and the members of Movimiento Cultural. As they cycle in and out of the batey, dancers seem to know it: they lock eyes with Diaz and other members of the group, magnetic as they play off of each other.

As it comes alive in Hopper College, the musical also feels like fate. Before Thursday’s opening night performance, Movimiento Cultural member and New Havener Kica Matos took the stage, giving a quick history of ex-Calhoun College—so named after a white supremacist to attract Southern students to Yale—to the smashed dining hall window, community protests and final acts of civil disobedience that led Yale to rename the building to Hopper College in February 2017.

The new name refers to Grace Murray Hopper, a computer scientist, engineer and naval officer who graduated with both a master’s and doctoral degree from Yale in the 1930s. For Matos, La Negra is a much-needed continuation of that renaming that echoes from Puerto Rico to Connecticut and back.

“Tonight, we reclaim this space,” she said.