If a walker is close to the taco trucks and the Long Island Sound, they can start with engineer William Lanson's nineteenth-century extension on Long Wharf, and the Black genius that transformed commerce in New Haven and built part of the Farmington Canal's infrastructure.

Or if they're closer to the State Street train station, they can stop where The Artisan Street Colored School was built in 1811, making its entrance of New Haven's first known Black School. They can stay downtown and make their way to a memorial to Joseph Cinqué and the Amistad Captives, learning about how a group of enslaved Africans aboard the Spanish-owned slave ship La Amistad fought for their freedom in Connecticut—and won—in 1839.

They can head out to the city's Annex neighborhood, and pay homage to the Quinnipiac People, who signed a treaty with the English in 1638 and were rapidly erased from both their land and the city's history. Or walk among the headstones in Evergreen Cemetery and discover Lt. Augustus Rodriguez, a Puerto Rican who fought in the American Civil War.

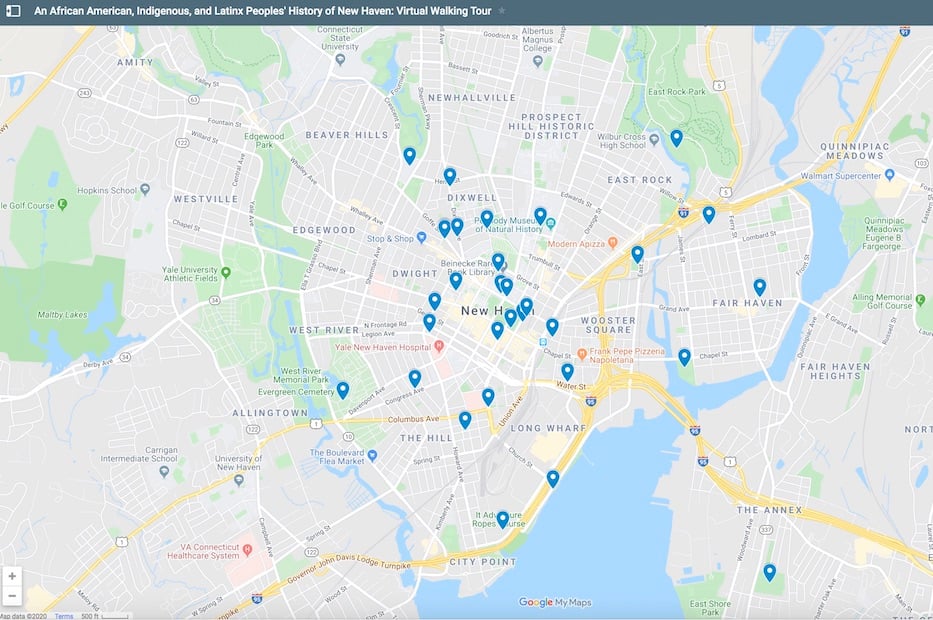

Those are just a few of the spots on "An African American, Indigenous, and Latinx Peoples' History of New Haven: Virtual Walking Tour," a new map created by 11th and 12th grade students at Metropolitan Business Academy. All of them are taking Nataliya Braginsky’s class on African-American and Latinx History, which was offered for the first time this academic year. Braginsky said that the map is a work in progress: students plan to continue adding to it throughout the year.

"The more people that know about New Haven's Black, Indigenous, and Latinx history, the better," she wrote in an email Friday morning.

The map, which is arranged chronologically, chronicles New Haven history from before the city's colonization in the seventeenth century through 2019. Sites span the city's 18.7 square miles, traversing sacred Quinnipiac sites in East Rock to Constance Baker Motley's graduation from James Hillhouse High School in Beaver Hills to New Haven's first integrated school on Edgewood Avenue.

It unearths some of the damage that urban renewal brought on the city, including the demolition of homes and businesses on Oak Street for an ostensible connector that cuts through the city like a scar.

There's a great deal of recent history, including the establishment of Junta for Progressive Action in 1969, election of John C. Daniels as the city's first Black mayor in 1990, formation of Unidad Latina en Acción in 2002, creation of the Elm City Identification Card in 2007, and Corey Menafee's smashing of a racist stained glass panel in what was then John C. Calhoun, and is now Grace Hopper, college.

In the process, they have spoken to just some of the struggle, resilience, vibrant culture and historical violence that lives within the city, but is rarely taught in its classrooms. In this sense, it feels both long overdue and right on time, a teachable resource for new legislation requiring Connecticut public schools to teach African-American and Latinx history.

It is likewise exciting to think of sites that might be added next, from infrastructure that cut Cedar Hill off from the rest of the city to New Haveners' advocacy for Wilbur Cross student Mario Aguilar, who was granted asylum at the end of last year.

"New Haven is rich in history of African American, Indigenous, and Latinx Peoples," the students have written in text that accompanies the map. "Yet this history is too often untold."

See more on the map, including interactive links, here. Many thanks to Metro teacher Nataliya Braginsky and her 11th and 12th grade students.