Arts & Culture | Arts & Anti-racism | EMERGE

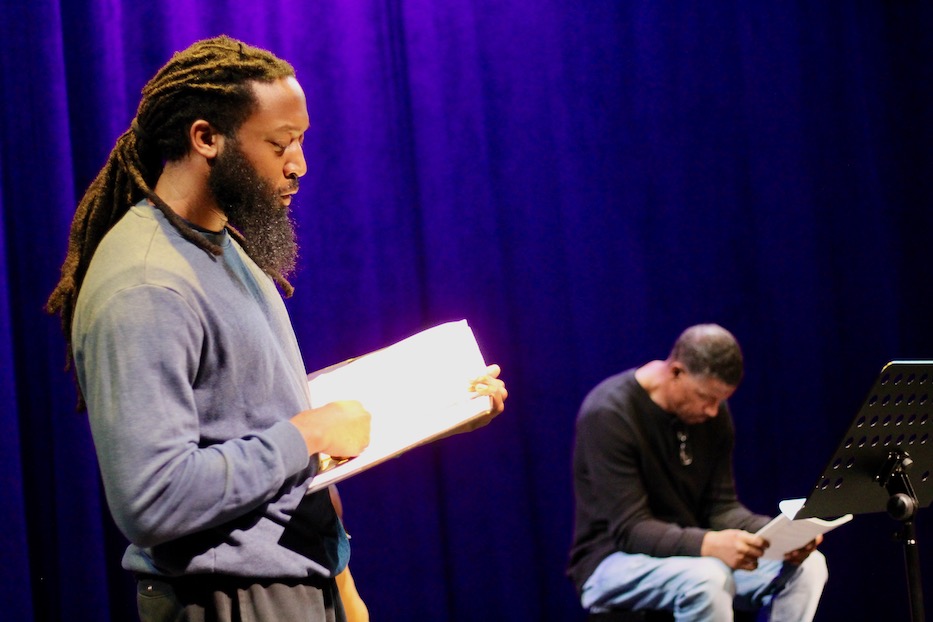

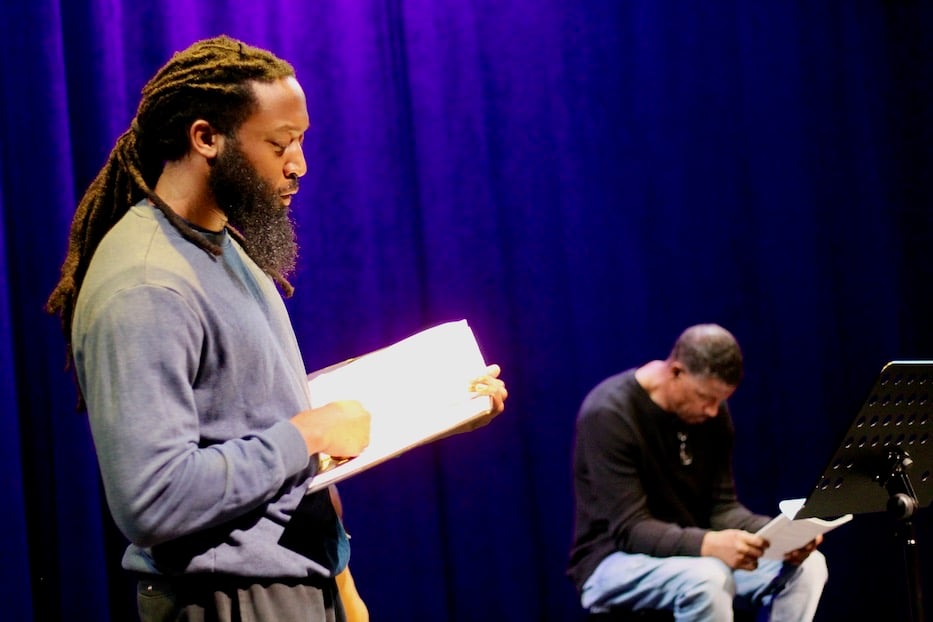

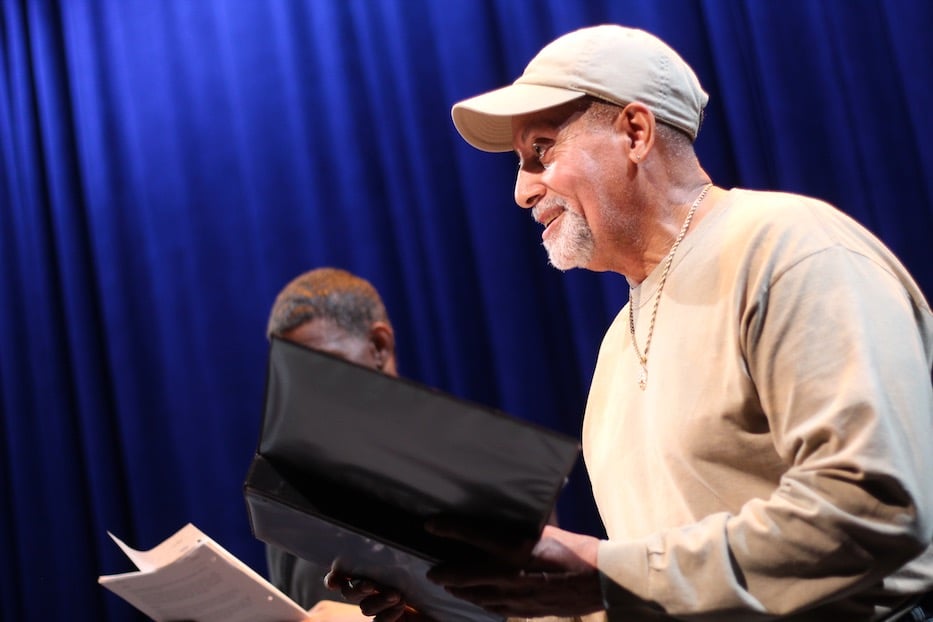

Tabari "Ra" Hashim.

Lights up on the bare stage. At the far left, Tabari "Ra" Hashim is a kid again, eating cereal as police descend on his neighborhood in the small hours before school begins. His eyes follow their gear-clad bodies, wondering what kind of strange game this is. It's his mother, an edge in her voice, who interrupts to let him know that it's not.

Hashim is part of As We EMERGE: Monologues of the Formerly Incarcerated, a collaboration between Quinnipiac University and EMERGE Connecticut that puts the narratives of formerly incarcerated people on stage and on screen. Pulled from hours of interviews and based on a 2018 project of the same name, the work premiered last weekend at Quinnipiac's Theatre Arts Center, and will live on as a documentary from filmmaker Travis Carbonella. The organization is still raising funds for the documentary; learn more and donate here.

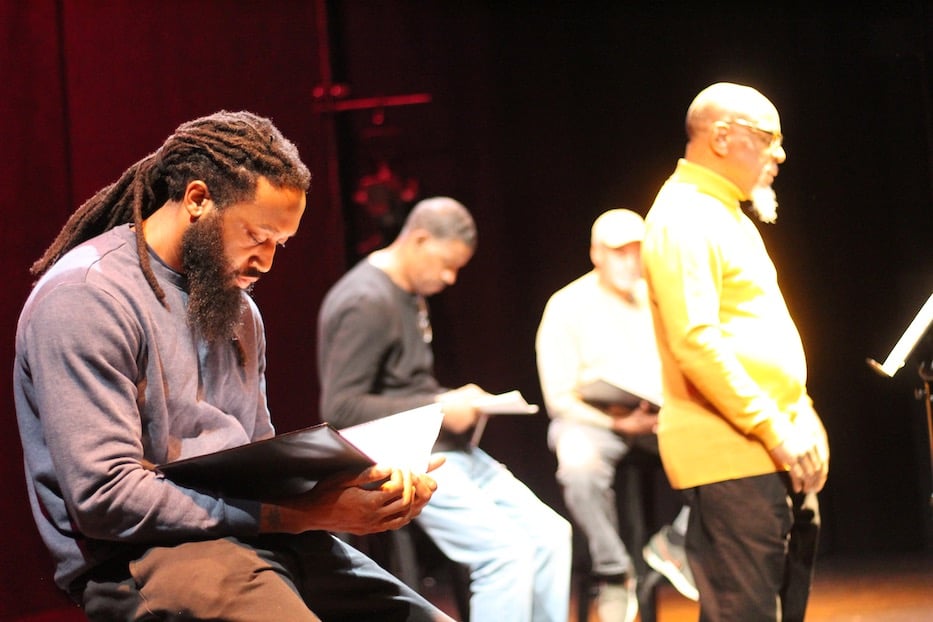

It has come together under the watchful eye of Alden Woodcock, executive director of EMERGE, and Rose Bochansky, technical director of visual and performing arts at the university. EMERGE is an organization that seeks to stem recidivism through job development, mentorship and professional training. This year, ensemble members include Babatunde Akinjobi, Hashim, Jimmy Robinson, Abdullah Shabazz and Vance Solman.

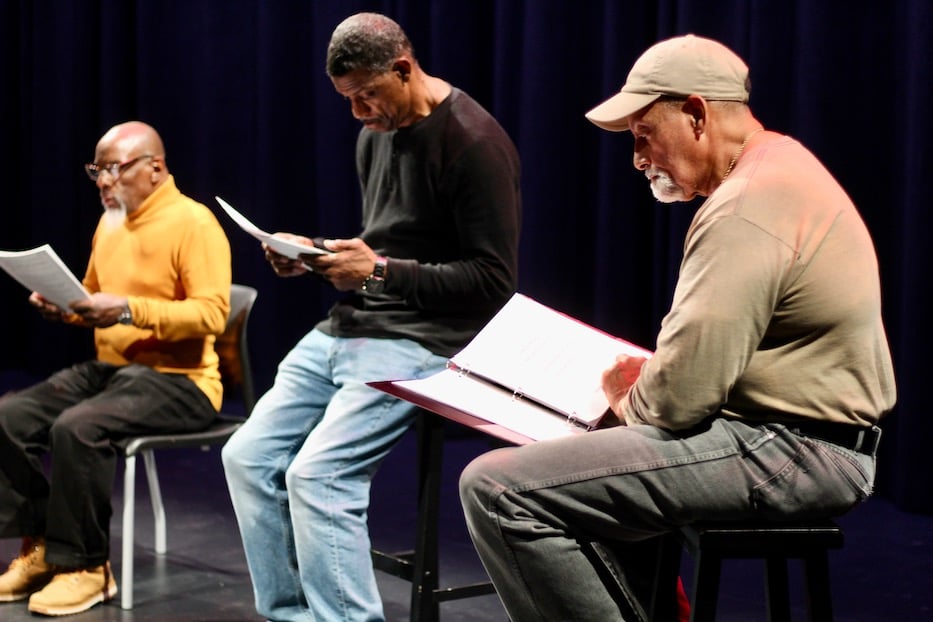

From left to right: Abdullah Shabazz, Vance Solman, and Jimmy Robinson.

"Unless you know somebody that's been through the criminal justice system, your association with people serving time is what you see in the media, on the 5 o'clock news, and the information you're getting is from the police," Woodcock said in an interview Tuesday morning. "This is to really change the narrative on how people think of what it means to be incarcerated and who is incarcerated. One of the most powerful things you can ask somebody is: 'What happened? And why?'"

It has very much been a labor of love. In 2018, the first iteration of As We EMERGE grew out of a joint venture between the university and the organization, in large part thanks to Dr. Don C. Sawyer, III. At the time, Sawyer was an associate professor and vice president for Equity, Inclusion, and Leadership Development at the university, as well as board chair at EMERGE (he is still the board chair at EMERGE, but has since moved on to Fairfield University). After seeing a similar presentation with veterans, he suggested that EMERGE bring some of its stories to the stage to give people a window into the people that EMERGE works with every day.

The idea was not only that that could be a narrative bridge; job development and engagement in the arts are also both linked to reduced recidivism (think of groups like Survivors of Society Rising and Theatre of the Oppressed NYC). At EMERGE, that approach works: only three percent of crew members return to prison within two years, which is markedly lower than the current statewide average. As We EMERGE, then, was and is a way to live the organization's mission and to teach people about the work it does every day.

But when Quinnipiac staff connected with EMERGE originally, "we didn't have a framework to talk to each other," Bochansky remembered at a tech rehearsal last week. At a community meet-and-greet, someone suggested she attend "Real Talk," a confidential weekly circle where EMERGE crew members discuss their lives, families, work, hopes for the future, and experiences in and out of prison. The interviews, and then the script, grew out of that. After EMERGE posted segments of that performance to TikTok last year, it began laying the groundwork for a new one this fall.

"I think the script came together in a week," Bochansky said, remembering the hours of labor and discussion that went into it. Like 2018, each story in the script is based directly on hours of taped interviews from members of EMERGE. Bochansky and a small crew then fit those chunks of dialogue together like the pieces of a puzzle, and decide what to keep and what to leave on the cutting room floor.

The result soars. As five men take the stage—and soon, the screen—the format works as a powerful statement for carceral reform, told with immense heart and as much vulnerability. Standing center stage, each character tells his own story, letting the narratives overlap and weave in and out of each other.

Akinjobi recalls growing up in Providence, and falling in love with drawing and illustration at a young age. Solman gets picked on in school and begins to take martial arts by the time he is eight. Robinson conjures his mother, who worked tirelessly and often under the gaze and oppression of white people to provide for her children even when the whole world was against her. When he talks about the family's move from the country to New Haven, a listener can feel the rude awakening and culture shock in their bones.

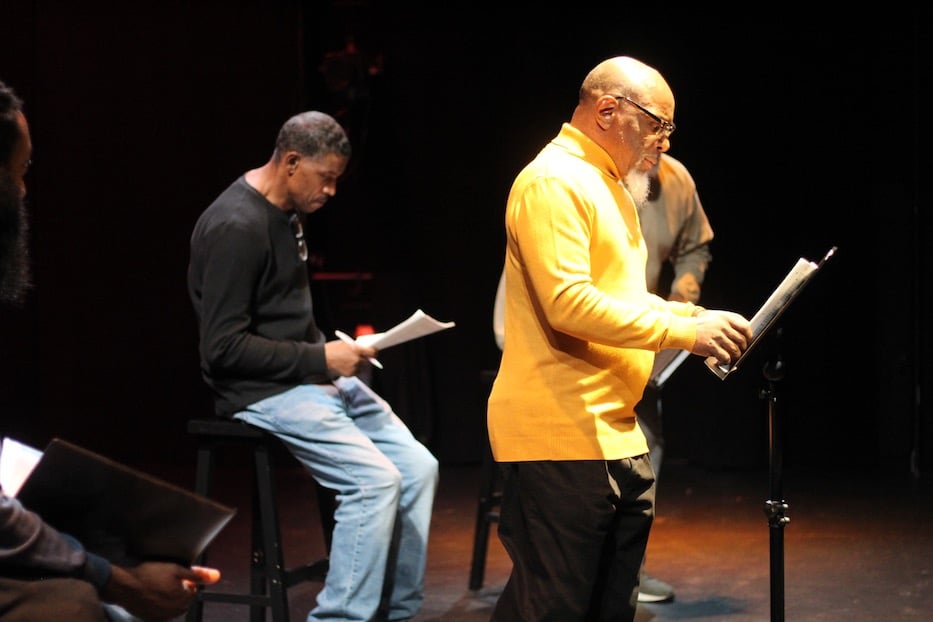

Jimmy Robinson and Rose Bochansky.

It reminds the audience that before they were reduced to numbers and sentences and soundbytes, these five men were children. They were Black boys with wide, soft eyes and an affinity for crayons and toys and colored pencils and the matriarchs in their families. They had dreams that were not so different from the dreams of those who may find themselves listening, hopefully with open ears.

The way these stories build is propulsive, bringing a listener into the show without introducing prison time or criminal history as a starting point. In Providence, Akinjobi desperately wants to attend an arts high school, and his disappointment is palpable when his dad shuts him down. Somewhere in North Carolina, Hashim is playing with toys, until he's told not to by the older boys in the neighborhood. In Philadelphia, Shabazz protects his brother from an abusive gym teacher, and watches as the framework of the school-to-prison pipeline emerges before his eyes.

All of them, in a way that is heart-rending and very real, learn what it means to be Black and male in America long before they should ever have to. All of them start to grow up prematurely. Or as Hashim says of school, "You're telling me the sky is the limit, but we're just going in one direction."

If there's a sense of inevitability here—listeners know that prison will intersect with these narratives somewhere—it's also one that exposes the wide, growing gaps in the social safety net that allow prison to happen. When Shabazz tells the story of losing his wife and unborn daughter in a car accident, he is also telling the story of deep, too-often undiagnosed trauma and a mental health crisis that is still unfolding in this country.

When Solman recalls dropping out of UConn and coming back to New Haven after just two weeks at school, overwhelmed by fatherhood and the birth of his young son, what he's also talking about is the lack of social and financial infrastructure for both parents and first- and second-generation college students in higher education. When Robinson turns to the streets as a source of income, it's because the world, from school to jobs, has already told him that he is somehow not worthy of a different path.

And when these wide, yawning gaps in society lead to gun and gang violence, to homicide, to robbery and PTSD and substance use disorder, they aren't signs of moral failure or talking points for someone's Thanksgiving speech about respectability politics. They are signs that the system, built by a small group of powerful white men who saw both land and people as property, was never meant to serve the same people it once enslaved and has since economically subjugated for centuries.

Instead, these are stories that a listener can and should take with them as they advocate for carceral reform. An attendee should feel a churning in their gut as Robinson describes Angola, the site of a former plantation where the Louisiana State Penitentiary now sits, home to prisoners that include children as young as 15 years of age. It's worth feeling surprise and outrage at sentences that go on for decades, like 40 years for robbing a jewelry store. Or perhaps they can take Hashim's unexpected love for literature, sometimes the pathway to an appeal, to push for greater access to information and within a prison's confining and cacophonous walls.

Indeed, when he says "they really train you to be like, 'this isn't a bad place,'" the discomfort a listener may feel seems exactly on time, if not overdue. Many of the characters speak directly to just how much psychological manipulation is involved in prison, and it's well worth the reminder. After all, how is a world that can lock people up, that can discount whole lives as subhuman, that can believe rehabilitation is possible in a cage—how is that world not already turned on its head?

It reminds a listener (particularly a listener who may not have any direct experience with the carceral system) that if they can suspend their judgment, even for a few hours, they might learn something about the cruelty, weight, and lopsidedness of the carceral state—and the audacity of joy and resilience that these men are able to hold onto.

At a recent tech rehearsal, ensemble members took time to smile, to pause and mull over lines, to laugh behind their half-extended palms at lines that have become inside jokes. When they reached a part of the script about smartphones—which didn't exist when each went into prison decades ago—they turned to humor as a balm, letting its healing power sit over the stage. For just a little bit, it was possible to forget the exhaustion of living with a sentence on your back.

That the work ends without a sense of resolution, meanwhile, feels right. For each character on stage, prison time has meant missed births and funerals, including during the very early days of the Covid-19 pandemic; it has meant extreme isolation and relationships that begin to feel conditional; it has meant brushes with death and suicidality and mental health crises that may be entirely preventable under a system governed by rehabilitation rather than power and punishment.

Even in moments that shine—the strength of spouses is very much there, as is the strength of Black matriarchs and of religion—this reality isn't supposed to feel comfortable. There's a loss there, and cast members allow the audience to feel it.

"Have some compassion," Shabazz says before a section on the rawness and trauma of reentry, and the words ring out over the half-lit stage. "Have enough compassion to learn the truth."