Culture & Community | Film | Arts & Culture | Arts & Anti-racism | EMERGE

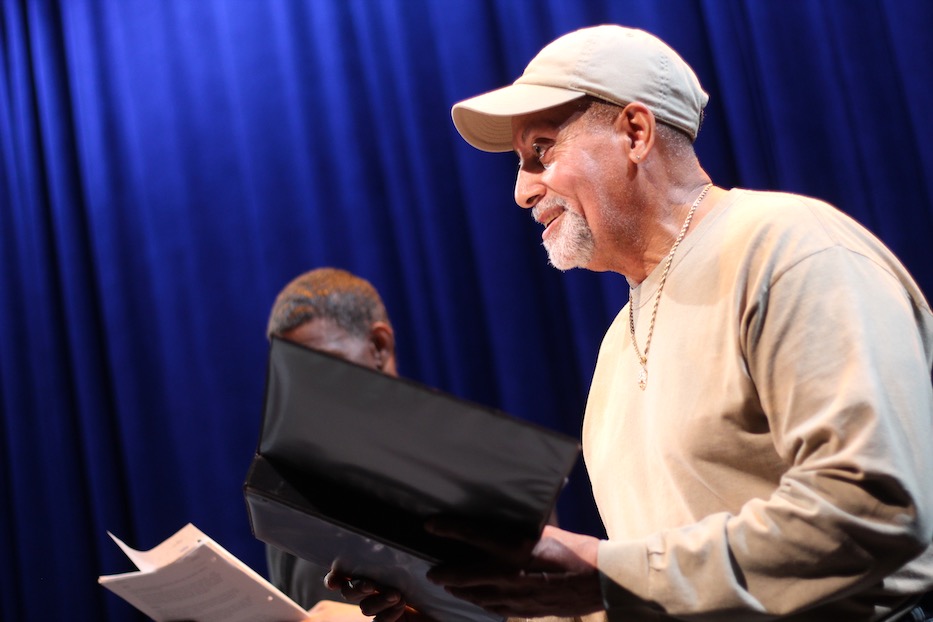

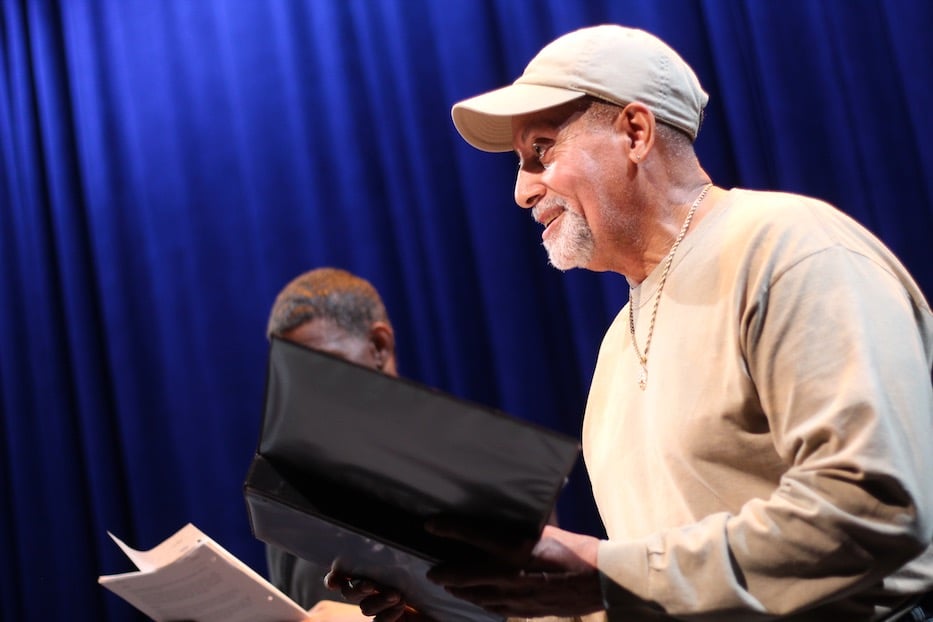

Tabari "Ra" Hashim at a rehearsal for As We Emerge: Monologues of the Formerly Incarcerated in November 2023. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

The camera is rolling. Babatunde Akinjobi stands to the left of the stage, skin nearly glowing in a pool of light. Already, the men around him have begun to tell their stories, narratives weaving in and out of each other. There is Abdullah Shabazz, grieving a wife and daughter gone far too soon. There is Tabari “Ra” Hashim, who can still see the cramped dimensions of a prison cell when he closes his eyes. There is Akinjobi himself, an aspiring comic book artist placed behind bars for a crime he didn’t commit.

For each, the carceral system is the thing that breaks—breaks bodies, breaks spirits, breaks families apart. “The system works the way it is intended to work,” he says to the audience, and the words hang heavy in the air.

So unfolds As We Emerge: Monologues of the Formerly Incarcerated, a new full-length documentary from New Haven filmmaker Travis Carbonella and the anti-recidivism nonprofit EMERGE Connecticut. Months after an eponymous performance at Quinnipiac University, the film is making its way across Southern Connecticut, with the goal of challenging preconceptions and stereotypes around the people and families caught in the crosshairs of the carceral system.

Screenings will take place at 6:30 p.m. on July 11 at the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury, August 2 at NXTHVN in New Haven, and September 26 at Housatonic Community College in Bridgeport. Tickets, which are free, and more information are available here. It marks Carbonella’s first full-length film, a longtime goal for the filmmaker.

“The hope was to change the narrative,” said Alden Ide Woodcock, who has been the executive director at EMERGE since 2020 and worked with the nonprofit since 2013. “I think that if you’re a numbers person, you know that the prison system doesn’t solve the problem. It is a punitive, emotional system, and we have to reimagine it.”

The road to the film, which Carbonella and Woodcock hope to submit to festivals, has been years in the making. In 2018, EMERGE Board Member Don Sawyer proposed the show as a dramatic project, in which EMERGE employees shared their first-hand accounts of the carceral system in a fully staged reading. At the time, he was Quinnipiac’s Vice President for Equity and Inclusion and an associate professor of sociology; he is now Vice President for Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging at Fairfield University.

It became a collaboration between EMERGE and Quinnipiac students and staff, particularly QU’s Rose Bochansky, technical director of visual and performing arts, and QU Professor of Criminal Justice Steve McGuinn. After interviewing EMERGE crew members and attending a weekly support group called "Real Talk," Bochansky worked on a script that knitted together peoples' stories. The show was a success.

But there was no framework to preserve the work, Woodcock said (it lives on in a series of TikTok clips). So when EMERGE secured funding from the Lewis G. Schaeneman Jr. Foundation and city Department of Arts, Culture & Tourism last year, Woodcock started thinking about how to revive the performance.

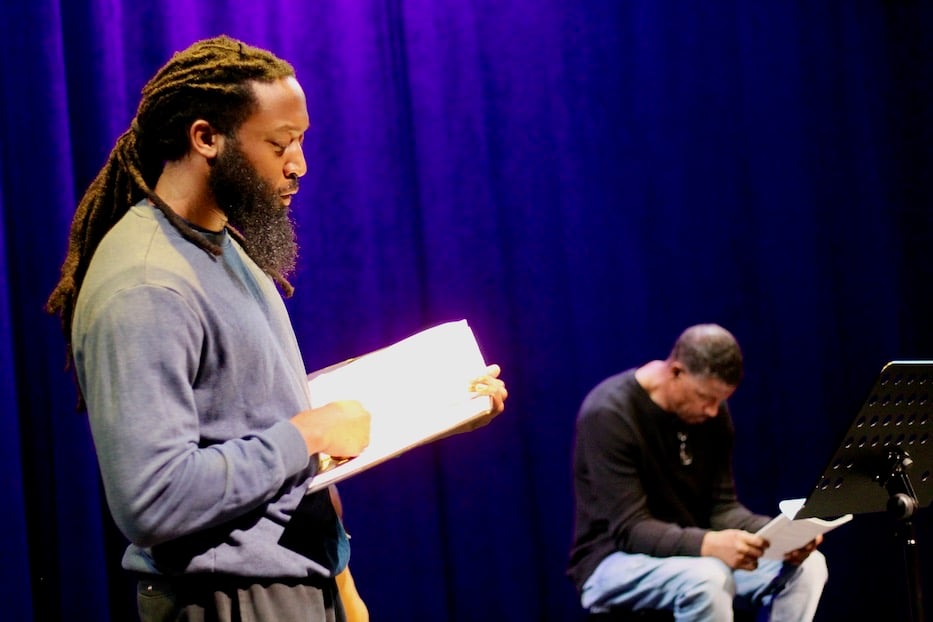

In the film, Carbonella documents the process from start to finish, following EMERGE crew members as they sit down with Quinnipiac staff and students, reflect on the carceral system, and ultimately build a performance. This time around, five men—Babatunde Akinjobi, Jimmy Robinson, Abdullah Shabazz, Tabari “Ra” Hashim, and Vance Solman—signed on to the projects, as did Bochansky, McGuinn, and several of his students.

With his camera rolling, Carbonella is there to record all of it. In an opening montage, crew members are out on a job, planting trees with the Urban Resources Initiative (URI). In the foreground, Hashim talks the crew through the process of planting the tree. A heap of fresh, damp peat sits near his shoes “You’re shaving it down nicely and gently, because we done found a root flare,” he says, smiling as he points it out. "And now that we found a root flare, we're gonna even it out, expose a root flare more so we can expose it to the sun and the water."

Carbonella and Woodcock.

It feels like a metaphor: in time, the tree will make the block a safer and more beautiful place to be, likely one of many new trees that neighbors request. In the summer, it will lend shelter and shade to those living in its branches and making their way down the sidewalk. As it grows, it will become a carbon sink, absorbing the gas from the atmosphere as it remediates toxic soil and contaminated groundwater below.

Hashim, who in the show describes his love for play, literature, learning and school, is doing the same. New Haven is that much better because he is in it, and because he is on the outside. Since starting As We Emerge, he’s become a host of the Pilot Language Podcast and has his own landscaping business.

It’s also a perfect place to start. From the outdoor sequence, Carbonella takes his viewers into EMERGE, which operates out of a Grand Avenue building in New Haven’s Wooster Square neighborhood. Inside (and later, at Quinnipiac’s Theatre Arts Center in Hamden) he becomes a fly on the wall, letting viewers witness interviews in which each crew member talks about life before, during, and after incarceration.

Each brings his own story into the room, creating a tapestry that holds both the bitter and the sweet. Akinjobi describes an early love for art, then watches it get taken away from him for a crime he didn’t commit. Shabazz, hesitant at first, recalls the traumatic loss of his family members in a car accident for which the other drivers, all high on cocaine, were never charged. Robinson recalls the impossibility of life—and of parole—in Angola, a dungeon-like Louisiana State penitentiary in which he spent 40 years, seven months, and two hours of his life.

While the stories are extremely unique—that’s part of the work’s power—there are several narrative threads that weave through each, showing audiences how inhumane the carceral system can be. All five of the men, for instance, talk about missing out on fatherhood, including those first few, precious moments of skin-to-skin contact after delivery. All of them miss birthdays, funerals, births and anniversaries. Many miss vital years with not only their children, but also their parents.

When Shabazz says “When you do time, your whole family do the time,“ a listener can feel the words, heavy and full of force. So too when Akinjobi acknowledges, simply, “we need each other.” It’s bigger than the project—it’s a mantra to live by. When he breaks down on stage remembering how deeply his mother has been “my rock,” we the viewers break down with him.

Jimmy Robinson, who takes the audience through his journey to reentry.

In this sense, the film is a powerful argument for carceral reform and a gift to those who could not make it to a three-day run of the show last November. Currently, the prison industrial complex is all about turning people into objects—that’s what federal registration numbers, inmate IDs, color-coded pie charts and statistics from the U.S. Bureau of Justice do. Carbonella, Bochansky, McGuinn, Woodcock—they’re all interested instead in storytelling, the oldest expression of that which makes us human.

It’s a device that busts right through the myths—perceived safety, perceived justice—that keep prisons in place. At one point, Solman matter-of-factly says “You feel alone. You feel nothing,” and he has distilled everything that is wrong with a system based on punishment and anonymity, rather than problem-solving, actual rehabilitation and policy change. At another, Robinson faces his peers before a show, taking in the cast, these stories, the words he’s about to speak onstage.

“I don’t know no other place that I would like to be than right here,” he says. It feels like a miracle.

Carbonella also pushes the story beyond As We Emerge’s three-day performance. When he’s not following the process onstage, in rehearsal, or in interviews, he’s with EMERGE crew members in their homes, visits that give the film a wider lens on who these people are and their lives in greater New Haven.

Robinson, for instance, introduces his 88-year-old mother, who he’s been able to care for since getting out of prison. Akinjobi, whose home is full of art, celebrates a birthday during the show. Shabazz talks to his son, with an As-salamu alaykum that feels like home. Solman, who recounts his 31 and a half years in prison, is diagnosed with emphysema and lung cancer and somehow takes the news like someone has delivered his breakfast order (he is now, thankfully, in remission).

It gives the film a sense not only of propulsion, but of a future. The whole point of EMERGE—to reduce recidivism through job placement and supportive community—works here. Only three percent of crew members return to prison within two years, which is lower than the current statewide average (a 2012 study from the state's Office of Policy and Management put that number closer to 50 percent).

In addition to their work, the five men in As We Emerge have gone on to become mentors, faith leaders, and workshop facilitators within and beyond the organization. Shabazz, for instance, is a mentor at the Huneebee Project and teaches a human history class at the Hassan Islamic Center, where he also leads Jum’ah service. Solman is part of New Haven's workplace reentry program. Robinson is a shop steward at EMERGE, and facilitates weekly “Real Talk” groups at the organization.

For both Woodcock and Carbonella, that’s the point: this film is meant to show the value of community, and of trust and mutual respect. Reflecting on the process—he can’t get through a viewing without crying—Carbonella said he doesn’t know if he would classify himself as an abolitionist, out of respect for people who are in that organizing work.

“I do believe that anything is possible with community,” he said.