Long Wharf Theatre | Arts & Culture | Theater | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

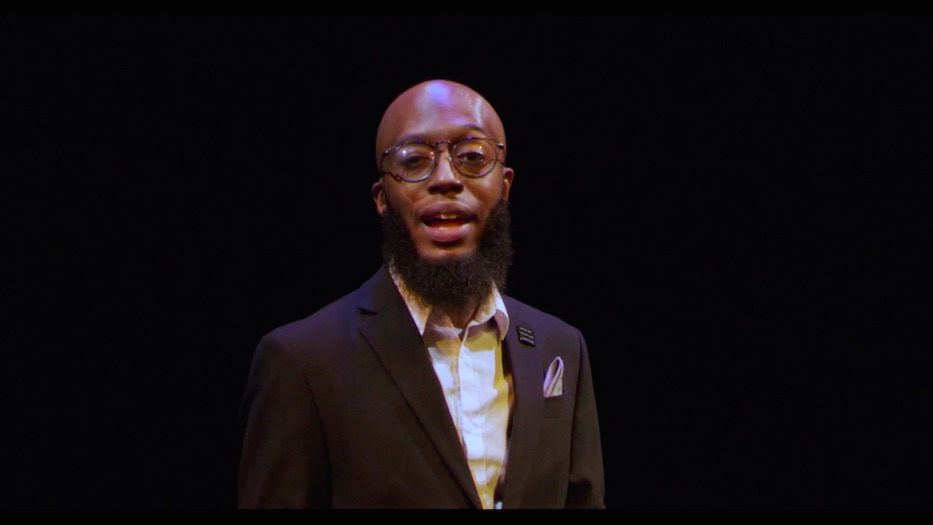

Masem Enyong in A Little Bit Of Death. Screenshots from Vimeo.

The darkness clung to Masem Enyong as she started to move, a silhouette glowing black and yellow at center stage. An arm reached out to the side, gliding through the air. She bounced, her feet communing in tone with the ground beneath her. Lights came up as she continued to sway, dressed in a canary yellow top and matching pants.

“Hi,” she said. The words ricocheted around an otherwise empty theater. “You thought it was gonna be all doom and gloom. Nah.”

Wednesday night, Enyong was a performer in Zulynette’s fifth annual A Little Bit Of Death, moved to Long Wharf Theatre in the first-ever filmed performance of the show. The work, which will be available for streaming through Friday night, joins Long Wharf’s current season “One City, Many Stages.” Like an artistic congress and reshaped New Haven Play Project that came earlier this year, A Little Bit Of Death opened with a call to center community, even from afar.

“A Little Bit Of Death is an invitation to say goodbye to things like old habits that no longer serve us, the struggle of living up to others’ expectations, laying down our armor to lovingly say goodbye to versions of ourselves we’ve outgrown,” Zulynette said in an introduction. “The show is a spell that centralizes BIPOC voices and queer voices. Tonight, some of the stories you’ll hear are being shared for the very first time. ”

The annual performance was first born in 2015, when Zulynette discovered and read Clarissa Pinkola Estes’ Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. The book cracked open worlds the artist, then based in Hartford, had never thought of before. Pinkola Estes introduced death not only as inherently female, but also as a very vibrant part of life.

“We have funerals, memorials, entire methods for how we say goodbye to loved ones,” she said. “This can be applied to us.”

Zulynette: “We have funerals, memorials, entire methods for how we say goodbye to loved ones."

Originally, Long Wharf planned to hold A Little Bit Of Death in Edgerton Park last month, as a live performance with limited capacity seating. When Gov. Ned Lamont rolled back the state’s guidelines due to rising COVID-19 cases, however, that vision became untenable. Inside the theater, Zulynette worked with Artistic Producer Hope Chávez and a group of artists to bring the work to stage and screen in six interwoven acts.

Wednesday, members of the show shed and hatched as they spilled their stories onstage. As she opened with dance and monologue, Enyong recalled growing up in a Cameroonian household, scrutinized by a strict grandmother that “had two Black girls” to tend to. For years, she couldn’t see eye-to-eye with her grandmother over the way she was raised.

As she spoke, she became a child again, moving around the stage to the first lines of Doris Day’s “Que Sera Sera.” She had gotten to the chorus when her grandmother slipped into her body, chiding her. Enyong’s posture changed: she was suddenly strict and domineering. Then she snapped back, reintroducing herself.

For a moment, she was Masem the girl again. Then she was Masem the boarding school student, responding to her alarm clock in the wee hours of the morning. Then Masem the young culinary artist, pint sized and bustling around a fragrant, warm kitchen with her grandmother. Or Masem the “plant mama,” planting corn with her own agronomist mother.

From a stage—and a screen—she let an audience unspool the intersections at which she stood. When she became a mom after hours of labor and a C Section, Enyong didn’t feel the rush of love she had heard about over and over again from other parents. Instead, she felt scared. As she spoke, a viewer could imagine her alone in a hospital room, holding a newborn baby boy.

“What came was concern,” she said. “I was going to be raising a little Brown boy.”

She transformed into another past version of herself, more current than the moultings that had come before. She scurried around a stage-turned-home, urging her son not to wear a hoodie out of the house. She begged him not to brandish a BB gun outside. She started in on “the talk,”noting that law enforcement officials may believe “you’re always doing something to them” by just being alive in a Back, male body. The fourth wall fell as she faced the audience.

“Right there, I realized … my grandmother wasn’t being a crazypants,” she said. “She wasn’t trying to stifle us. She was just trying to protect us. She was trying to keep me alive.”

Those realizations are now ones she brings to her own life as a mother, fierce gardener, and teaching artist. When she steps into the classroom, she’s remembering her father’s educational legacy. When she prepares a meal for Thanksgiving—a tradition once foreign to her as an immigrant—she is back in her grandmother’s kitchen, overjoyed to be filling bellies with her food. When she buys plants, she channels her mom and it lifts her spirits.

“Something about planting things just to watch them bloom,” she said, her body swinging to Prince Nico Mbarga’s “Sweet Mother.” The music faded. So, here I am. A whole me. I realize that I don’t have to be stuck. Anytime I feel like I don’t know what to do, I can just reach back for those memories and experiences right there. I have everything I need to help me grow through life.”

As Zulynette narrated, acts stitched themselves together, each moving parts of a sudden, surprising whole. Taking the stage with an old photograph that she kissed, Diana Aldrete opened her story with a spoken word piece turned prologue, a kind of prayer for self discovery and rediscovery. She pulled the audience back into her history with her own name.

“And in this present moment I reclaim her name, as I climb past the callus bones of this ribcage, past the belly, past the shadows of my existence,” she said, speaking to both the empty theater. “I discover a rusty key, buried within the catacombs and the archives. I open my chest and search for her in all this rubble.”

Aldrete is an artist and a scholar, navigating what it means to live in and between those two worlds. She in a queer Latine, an identity with which she wrestled for years. She is Mexican and Midwestern, and living somewhere in the middle of the two at any given time. She is a survivor of her own worst thoughts about herself.

“I want love to take over the impulses that brought so much devastation to myself,” she said, recalling a period that was so dark she considered suicide. “Love for myself and all the young queers who have suffered desperate attempts to fit into coffins that would eventually kill our spirits because we think we are the problem.”

Aldrete lifted a guitar as she spoke, pulling it to her chest. In a nine-month stretch that has shuttered both music venues and theaters, the first chords echoed over the space and instantly felt like a long-lost friend. Her voice coasted upwards, the lyrics sweet and full in the space. When she laid down the guitar, she pulled the audience back to her childhood, spent between Milwaukee, Wis. and Mexico.

For years, she said, she questioned her parents’ decision to immigrate and raise her and her sister in the United States. Then she realized that their sacrifice came with a unique opportunity.

“Because I am a U.S. citizen, it is my obligation to criticize the U.S,” she said. “I call death to the binary notions of culture. Death to both hetero and homonormativity as normalizing what kind of ‘queer’ is acceptable. Death to constructions of love and what that should look like because patriarchy. I want more stories of romance. And for stories of love to be painted different colors over bodies that I recognize.”

Aldrete told the audience that she’d had to “kill the rhythm in my accent,” and decried both the primacy of English and an American expectation of monolingualism. She denounced the Mexico-U.S. border, weaving between English and Spanish as she described a “moving line on Indigenous lands.” She called for an end to white supremacy and its devastating aftershocks.

“Death can invite the creation to imagine new possible futures,” she said before belting Rufus Wainwright’s “Going To A Town.”

Zulynette and Ebonie Goulbourne: Unfucking.

Midway through A Little Bit Of Death, Zulynette returned to the stage with Ebonie Goulbourne to discuss “how to unfuck ourselves.” Sitting in armchairs on Long Wharf’s stage, it could almost have been mistaken for a talkback or minimalist, pre-pandemic set. Until the two began to speak, and the pandemic lurked everywhere.

Goulbourne explained that she had started thinking about the unfucking process during the first weeks of COVID-19. In Connecticut, Gov. Ned Lamont issued an executive order to shelter in place on March 19. Goulbourne’s birthday was March 20. She was supposed to be getting onto a plane to Aruba.

“I was stuck, having to listen to my own thoughts and feeling the pressure to do more healing than I was already doing,” she recalled. “It all, just, boom, blew up in my face.”

She began thinking about the relationships that had broken and soured around her. There was the relationship with herself, and the thoughts that were often chattering in her head. There was the relationship with her mom, and another with her siblings. The relationship with her friends.

She traveled back into deep the folds of her memory, probing when her fierce independence started to seem like aloofness to the people around her. She dug into therapy. She spoke about her therapist, a white woman named Joanna, so candidly that it seemed she was a third character on the stage.

“She asked me if my ancestors, if my family, would really want me to just be suffering in order to honor them,” she said. “I wasn’t too happy with that.”

She kept digging, she said. She did yoga every day, until it became a kind of rigorous ritual. She sweated. She got in touch with her breath. She moved into her body and quieted her mind. The practice ultimately convinced her to leave a job editing resumes and cover letters.

Nine months into the pandemic, Goulbourne is doing a kind of career coaching that works for her, in which she talks to people about their dream jobs. She said that has been part of the unfucking process.

“I got inside my body,” she said. “I stopped hiding from my process. I showed up. And instead of spending time on the yoga mat ‘oh, what is this other person doing’ … I was just in my body. Which then created the space for me to receive these downloads. Which then creates the space for more work to be done.”

Andrew Dean Wright.

If “One City, Many Stages” is also designed to speak to the moment, Andrew Dean Wright probed not one pandemic, but two. Wednesday, he took center stage between dried flowers and a headstone bearing his name, telling the story of his own two-month fight with COVID-19 during the height of Black Lives Matter protests earlier this year.

Following the state sanctioned murder of George Floyd, Wright watched from home as protesters filled the streets. He was so sick he couldn’t leave his bed. He started to wonder if the virus that kept him inside—the thing that was also ravaging his body—was a good thing in disguise.

“I’m sure I don’t have to do too much to remind people of the kinds of things that have been lost this year,” he said. “I’m staring at my ceiling, wheezing, hearing people on the news chanting ‘I can’t breathe.’ Frustrated, because I can’t be there too.”

If he went out, Wright knew he could “be martyred” in any number of ways, simply because he is a Black man. It could be a cop, pulling a weapon or a body part on him completely unprovoked. Or a white supremacist. Or a force he hadn't yet even identified.

“It feels like there isn’t a spot in creation where I can be safe,” he said. The words hit one by one, deliberate and sharp. “Where mistakes are forgotten.”

Wright described a journey through depression, soaking his vignettes in shades and shocks of blue. He sped up, threading a needle straight from COVID-19 to the country’s deadly toll on Black bodies, and on to a religion that sometimes turns a blind eye to both. He motioned to the headstone at his feet, where his own name was etched in white letters.

“I’ve been thinking what murder is to an absurdist/when all your prescribed cures are ineffectual,” he said. “Or just hurt me worse. When it feels like the world is round, so whatever ground you’re standing on, they’ll be back to kiss you good night.”

Line after line coasted into the empty theater. As he read, Wright put a sort of lyrical death to perfection, to expectation, to the revisionist history of a country that has demanded both. He worked toward resolution, his voice warm but steady. He wrapped a lover into his verse. Then a fellow artist. He conjured a couple, delighting over their young son. His voice became full of light.

“When things are good, walk with me,” he said. “And when they aren’t, we can dance to each cacophony we may find within this lifetime. Let’s show the universe that we can move as gracefully through the darkness as we ever have through the light shine.”

Performer Jas LaFond closed the performance just as it had begun, with movement and story. Framed by “wanted” posters with their own face, they whooshed onto the stage to the first notes of Elle King’s “Baby Outlaw,” holding a cane with one hand as the other sliced through the air. In a sort of saloon-meets-steampunk style, they swayed to the music, lifting the cane as if it was a rifle. A bang, and the music fell to a hush.

LaFond soaked the audience in memory, jumping from a conversation on their recent weight gain to a department store some years ago. They found themselves among racks of cotton and polyester, unsure of whether to choose clothes from the girls’ section or women’s section. In the contours of LaFond’s voice, it became easy to imagine them walking through a store with bad fluorescent lighting, inspecting clothes that did not seem made for them.

“My mother warns me not to bust out of my clothes, not to add any rolls because a wanted body is a body that is not fat,” they said. “I take to wearing only t-shirts and jeans until I hit 13. But now? I am that big bodied bitch.”

They tore down one of the wanted posters and danced into another memory. This time, LaFond stood at a doorway of their mother’s bedroom, admonished for the thought that they might be bisexual. The memory switched as music played overhead.

They were singing a solo on stage for the first time, and their mother wasn’t in the audience. Not because she didn’t want to be, but because she couldn’t afford a Lyft to the performance, and the auditorium didn’t have the right accommodations for someone with a disability. The music rose once more.

The memory changed. LaFond was walking through Montreal with their new husband. They noticed that shop owners seemed comfortable when they walked in. When they walked around the city by themselves later, “without the cloak of my husband’s whiteness,” they were amazed to see that people regarded them exactly the same way.

“Is this what it’s like to be treated as five-fifths human?” they asked.

As they toggled between weight, ability, sexual orientation and American anti-Blackness —all while in drag—they laid to rest the myth that disabled bodies, fat bodies, and non-white bodies are in any way less than. It felt like a period on the show.

“They’ll ask us about 2020,” Zulynette said just before that final act. “We’ll tell them: When so much pain could have been prevented. When whole administrations and their supporters wanted us dead and gone. What did we do? We had the audacity to live.”

Watch A Little Bit Of Death here through 6 p.m. Friday night.