Culture & Community | Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS) | Refugees | Sanctuary Kitchen | Arts & Culture | Culinary Arts | Arts & Anti-racism

Hossna Samadi.

When the Taliban invaded Kabul last year, Hossni Samadi thought back to her childhood in a teacher’s basement in Afghanistan, where underground school was the only option for young women and girls like her. Twelve months later, she is still terrified for the future of women in her home country—and speaking out against the oppressive regime that has ended their rights.

Samadi is an Afghan refugee who came to the U.S. in 2016, and has since become a translator, vocal advocate for women, co-founder of the Collective for Refugee & Immigrant Women's Wellbeing (CRIW) and program associate at Sanctuary Kitchen at CitySeed. Last Thursday night, she joined four speakers for an hour of storytelling, resource sharing, and information on the current state of human and women’s rights in Afghanistan. Almost 50 attended via Zoom.

The event, sponsored by Sanctuary Kitchen, came almost exactly a year after the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan on August 15 of last year. For an hour, speakers—almost all Afghan women who are refugees and the children of refugees—made space for the deep grief and pain of the past year.

During that time, Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS) has resettled 604 Afghan migrants. Sixty percent of them are children under the age of 18, according to IRIS Director of Community Engagement and Co-Sponsorship Ann O’Brien.

“This marks a significant time not just in Afghan history, but in world history,” Samadi said at the top of the evening, pausing several times as she began to cry. “It’s a day that we handed over a country to a group that doesn’t believe in human rights, that doesn’t believe in women’s rights. Every single rule that’s coming out every single day is about women. This is the only government on the earth that I know that has the biggest problem with women. ”

In addition to Samadi, speakers included New Haven-based, Afghanistan-born public health liaison Sumaira Akbarzada; artist Azita Ibrahimi, a former lecturer at the University of Herat who is now living in a refugee camp in Germany; Elena’s Light Founder and Director Fereshteh Ganjavi; and O’Brien.

Donna Golden, who leads CRIW with Samadi and Rachele Pierro, ceded her time so that fellow speakers could meet the one-hour mark. She did say that CRIW is focused on mental health resources for refugee and immigrant women, often a taboo in their home countries.

“I Survived”

Slides during a presentation from Sumaira Akbarzada. Screenshot via Zoom.

Throughout the night, speakers urged attendees not to let Afghanistan fade from their minds.

In a simple, crisp pink top and black hijab, Samadi began to tell her story just after 7 p.m., a single voice among the patchwork of faces and backgrounds floating on the screen.

Behind her, an image of 10 Afghan girls, all masked and hunched over their desks in hijabs, shifted into focus. After a PowerPoint outlining the mass hunger, rise in poverty, human rights offenses and rapid, violent removal of women’s rights in the country, she tried not to cry while speaking.

“The position every girl in Afghanistan is in right now, I was in this position almost 20 years ago,” she said. “I survived. I don't know if I can say the same for them.”

Born and raised in Afghanistan, Samadi was still a child during the Taliban takeover of the country in 1996. Overnight, her basic human rights as a young girl disappeared. She was no longer allowed to attend school. Around her, women were removed from their schools, universities and workplaces, told to perform domestic tasks in the place of the careers that they had spent years building up. She remembered feeling terrified.

Even as a girl, she knew it wasn’t right—and so did her parents. In the late 90s, Samadi began attending a one-room underground school for girls between the ages of six and 18, held in the dark, hushed basement of her teacher’s home. To keep the space secret, students arrived at a different time each day, because “the teacher didn’t want the Taliban to get suspicious of anything that is happening in that house.”

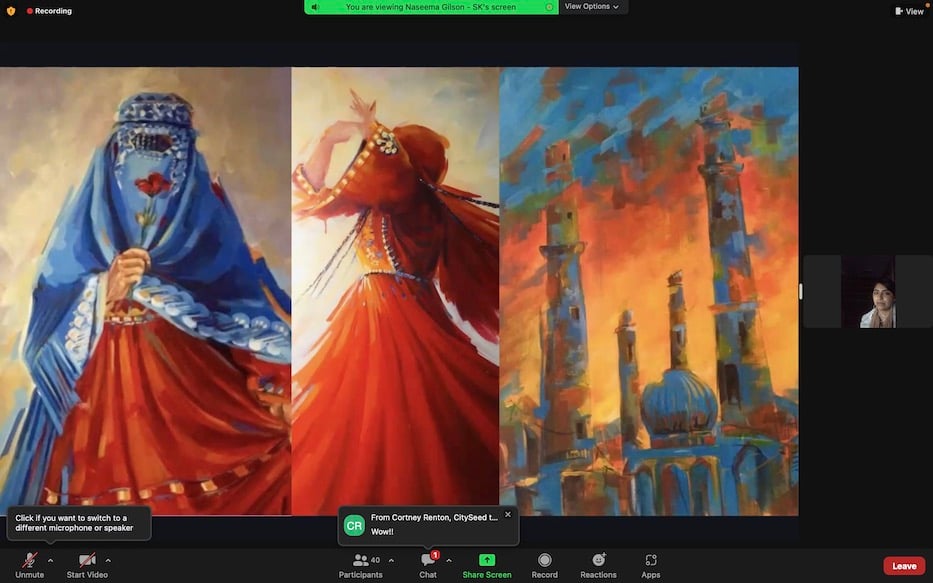

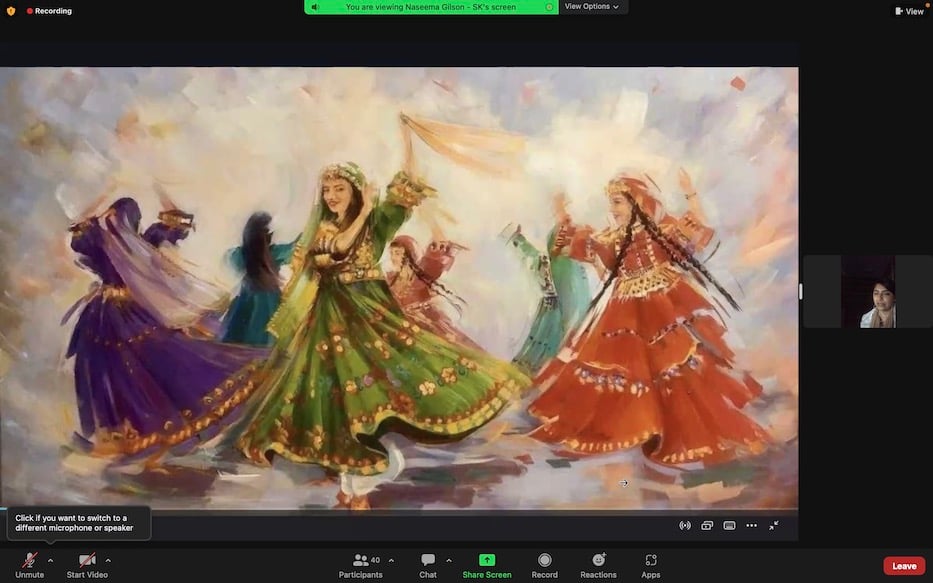

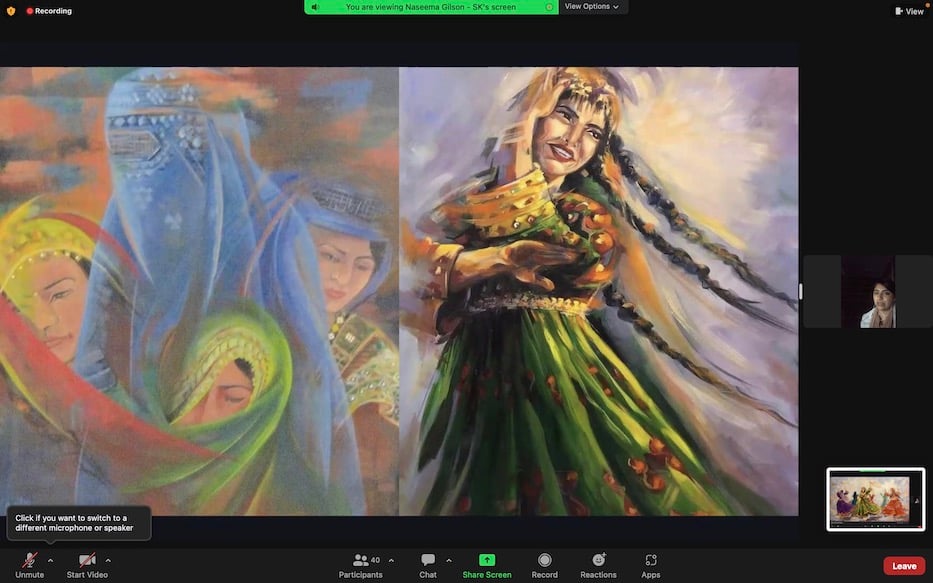

Work by Ibrahimi. Screenshot via Zoom.

At the time, she said, she was simply trying to get an education, and didn’t always think of how her life, and her teacher’s life, was constantly at risk for the pursuit of a basic human right. Two decades later, she understands it very differently.

“What I’m thinking right now, I think we were fearless,” she said. “And my teacher was the bravest person. We were basically committing a crime in the eyes of the Taliban.”

When the Taliban fell after U.S. intervention in 2001, Samadi watched women reclaim their lives “with a lot of struggle and hard work.” As they returned to schools, universities, newsrooms, hospitals, and professional workplaces, she grew up. She married her husband Farid, who worked for Chemonics and USAID in Afghanistan.

Six years ago, as it became clear that the country was no longer safe for them, they came to the United States as refugees. While the two have built a life in the United States, she said, several of her relatives remain in Afghanistan—meaning she is never not thinking about life in her first home country. That includes the 3.5 million Afghan girls who until last summer were enrolled in school, and able to access some form of education in their home country. Now, girls over 11 are forbidden from attending school.

When she heard that the Taliban was approaching the capital city of Kabul last year, Samadi recalled feeling disbelief, then doubt, then total shock and devastation. For years, she had watched the regime’s grip tighten on parts of the country, but believed that Kabul was safe. She was watching the news when she first heard that the city had fallen. She was still watching three hours later, when “a reliable news source” confirmed the report.

Naseema Gilson, program director at Sanctuary Kitchen, is the child of an Afghan immigrant. Screenshot via Zoom.

Initially, she said she was hopeful that the Taliban would allow women to continue attending school and to work as they pledged to defend women’s rights “within the limits of Islam.” Those hopes gave way to devastation within days, if not hours. In an interview with the Arts Paper last year, Samadi described lying awake into the early hours of the morning, unable to pry herself away from the news of what was happening on the ground. She is most worried for the women and girls growing up under the strict and deadly Taliban regime.

“They changed for the worse,” she said of the Taliban. “They are angry and resentful at having fought for 20 years. Their answer is, ‘You had 20 years of foreigner involvement while we fought and lived in the mountains.’”

Holding back tears, she spoke of how often she experiences survivor’s guilt as someone who was able to leave the country. She expressed deep frustration at the U.S. government and the Biden Administration, the European Union, and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) for making promises of foreign aid that she feels they did not keep.

“Afghan women are standing alone in this fight,” she said. “They are alone. Afghan women who have escaped Afghanistan are struggling with PTSD and language barriers.”

For that reason, Samadi continued, she’s also focused on real-time solutions for new arrivals, like providing reliable transportation and childcare, ESL and EOSL tutoring, and translation help. She invited those listening—and by extension, each of their networks—to get involved if they have not just the financial resources to help, but also the time to be of assistance.

“I Brought All My Goals With Me”

As Samadi passed the virtual mic to her fellow speakers, all of them echoed that sentiment. Many in the room urged people to provide for their neighbors in need, from financial assistance to volunteerism. In addition, they filled listeners in on the human rights abuses, widespread food insecurity, and complete disregard for women’s rights that are taking place on the ground in Afghanistan.

At times, it seemed, it was hard for both presenters and for listeners not to break down entirely. Speaking to attendees from a refugee camp in Germany, Ibrahimi traced her own path to a lectureship in art at the University of Herat, a position for which she was once celebrated. Now, that same skill has become a potential death sentence in the only place she has ever called her home.

Ibrahimi’s story starts where Samadi’s does. In the 1990s, she too was a child under Taliban rule, with “goals and ideas” of her own, and also the knowledge that it was illegal for her to learn to read and write. She was 11 years old when the Taliban fell in 2001, and her entire “gates of education” opened up overnight, she said. She, with millions of women and girls, felt as though they were seeing the sun, she said.

Work by Ibrahimi. Screenshot via Zoom.

“I was like a bird that had just been delivered from a cave, and did not know which song to sing,” she said. Alongside her classes in school, she began to study painting and drawing. She fell in love with the practice, she said—words that come to life on her bright, detailed canvases of women in burquas, Buzkashi players, and Afghan women in motion, their bright skirts billowing as they move. From an undergraduate degree, she pursued a graduate education, and then a doctorate. She became an educator not only because she loved learning, but also to share that joy.

And then, a little over a year ago, the Taliban began approaching her city, located in Western Afghanistan. For her, Herat no longer felt like a safe place to be a woman. She made the move to another country not because she wanted to leave, but because she felt that she had to. She still sells her artwork, but is far from the place that once nourished it.

In Germany, the clock inched toward 2 a.m. A deep night fell outside the window from which she was speaking, blanketing the outside in a thick, velvety blue. She took a beat and pushed forward.

“For me, leaving Afghanistan is leaving everything I have ever worked for,” she said. “I want to say that I brought all my goals with me, and I am sure there are lots of women who have similar goals as mine.”

A graduate of the Yale School of Public Health who came to the U.S. as a young refugee, Akbarzada looked to an ongoing, deepening public health crisis in Afghanistan that is far more severe and more deadly for women and girls than their male counterparts. Even before the Taliban takeover, she explained, barriers to safe healthcare were high—and so were rates of infant and maternal mortality. Now, those numbers are skyrocketing.

It’s due to a constellation of public health crises all hitting at once. In the year since the Taliban takeover, many of Afghanistan’s healthcare facilities have been stripped of the basic resources they need to operate. At the same time, Amnesty International has reported that the rate of forced and underage marriage has risen. When girls are forced to marry, Akbarzada said, they are more likely to experience “early and closely spaced pregnancies,” which are not safe for the health of the child or the young mother.

Akbarzada also looked to the Taliban’s 2021 mandate that women cannot travel over 45 miles without a male relative—a rule that is impossible in many households where fathers, brothers, uncles and even boys are no longer present, and a healthcare facility of any type may be much farther away. In addition, women can no longer be seen by male practitioners—making it more likely that they will not get care at all.

For Akbarzada, the work is personal. In the years since her arrival in the U.S., she has dedicated much of her young career to helping refugees navigate a new and unfamiliar public health landscape. Last year, she worked with IRIS, the Yale School of Public Health, and the Rockefeller Foundation to get free Covid-19 saliva testing to Afghan refugee families. She now serves as a community liaison at the Yale School of Medicine.

She encouraged attendees to support Afghan-led, trusted organizations such as Women for Afghan Women (WAW) and Elena’s Light, as well as refugee resettlement efforts across Connecticut and the United States. She pointed to Afghan female artists like Ibrahimi, many of whom operate businesses through outlets like Instagram and Etsy.

“These all might seem like small efforts or steps, but they will make a lasting impact,” she said.

Closing out the evening as they spoke, both O’Brien and Ganjavi brought that message home. Giving attendees a sense of resettlement efforts in Connecticut, O’Brien said that IRIS has resettled 604 Afghan nationals, and a total of 904 refugees, in the last calendar year. One year in, the agency has helped new resettlement efforts in Texas, Pennsylvania, and Ohio get off the ground.

Getting visibly choked up, O’Brien shouted out a number of statewide partners on the call, who have become part of a ramped up effort to welcome refugees not just in Connecticut’s cities, but also its smaller towns and quiet corners. As she and staff at IRIS continue to resettle families, those partners have become invaluable.

She added that the landscape is constantly changing: there are now Afghan families who, unable to go directly to the U.S., have traveled to Mexico and are trying to cross at the border.

“We knew we needed our entire community,” and watched as they stepped up time and time again, she said. “It has been really an incredible, incredible year.”

Ganjavi, who came to the U.S. as a refugee with her family in 2011, urged those on the call to get involved in their own communities, and to educate themselves about the situation in Afghanistan. Days before the Taliban invaded Kabul, she remembered talking to an uncle who was still in the country, who told her he had received orders not to fight their advances. Then came a text message from an American friend, asking how she was doing. At that moment, Ganjavi felt incensed.

“How does she not know my feeling?” she remembered thinking. “It was the saddest moment in my life. My entire life. It was so hard to see what you build, what your community builds, and then it all goes overnight.”

In the face of that pain, she said, she often thinks of the power of collective action. At Elena’s Light, volunteers provide women refugees with in-home literacy help, ESL and EOSL classes, health education, and child wellness programming. The organization is named after her first child, a daughter named Elena.

“What we can do right now … now we have a group of people, 76,000 people, all they need is love from us.”

Learn more about Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS) here. Learn more about Elena’s Light here. Learn more about Women for Afghan Women (WAW) here.