Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Woodbridge | Palestine Museum U.S. | Sculpture | COVID-19

Screnshots via Zoom and Facebook Live.

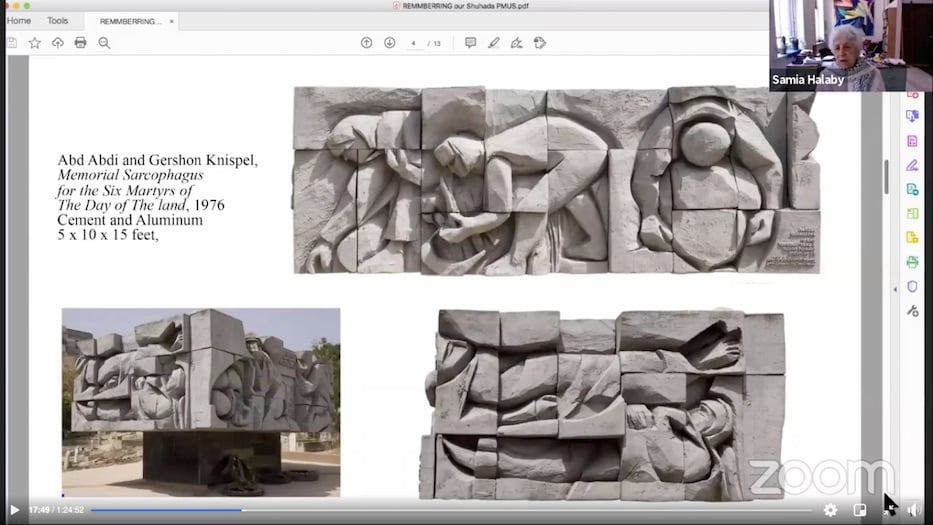

Abed Abdi and Gershon Knispel's Memorial Sarcophagus for the Six Martyrs To The Day of The Land rises from the ground in aluminum and grey cement, heavy from the moment a viewer puts their eyes on it. On one side, two bodies lie one atop the other, chiseled and molded to look larger than life. On another, a body leans forward, reaching towards the land. It feels like a puzzle cube, where every side is a potential step towards death.

The monument, completed by a Palestinian and an Israeli, is from the late 1970s. It feels as though it could have been sculpted last week. Saturday, the Palestine Museum U.S. showed just how current—and to many, freshly painful—its history still is as it launched its annual Palestine Art Week online.

The programming, which runs through Friday, is available on the museum’s website and on Facebook Live. Saturday, it included live reports from Gaza and musical performances of Zeinab Sha’ath “The Urgent Call of Palestine,” which she and Ismail Shammout first recorded almost five decades ago. When she appeared to sing on Saturday, bright Eid decorations were still strung up behind her.

"Today, we salute Palestinians around the world, but particularly in occupied Palestine, in Jerusalem, and in [the] Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood as they stand in the face of land and property theft," said Faisal Saleh, founder and executive director of the Palestine Museum. He spoke of the multiplicity of the Palestinian diaspora, and welcomed attendees from around the world.

The week of programming began on the 73rd anniversary of the Nakba, or the exodus of Palestinians from their homes during the Palestinian War in 1948. May 15 is known as Nakba Day; the Arabic word translates roughly to "disaster." This year, it comes in the midst of attacks from the Israeli government on Palestinian civilians, in both the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem and in Gaza. Hamas has responded to Israeli airstrikes with rocket fire.

As of Monday, the death count included over 200 Palestinians, 59 of whom were children, according to reports from health officials cited in the Guardian. According to Reuters, 10 Israelis have died.

Over and over again, speakers noted that the violence is not new: it stretches back centuries to the invasion, seizure, occupation and division of the land by Ottoman, British, Jordanian and Israeli forces (read more of that history here). In April of this year, Human Rights Watch identified Israel as an apartheid state in a 213-page report, calling the country guilty of “crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.” Israel swiftly refuted the report as propaganda.

In an opening panel, artist, lifelong activist and writer Samia Halaby guided viewers through a close looking exercise that was equal parts art history and social justice. She dedicated it to “Al Shuhada,” or the martyrs of liberation past and present.

“I want to remember those artists, who in revolutionary times are very forward looking, and very united with each other,” she said. “Almost each and every Palestinian artist is part of a sisterhood, brotherhood that feels very close to each other. Denied daily contact in Jerusalem and regular contact within Palestine, we have managed to make precious any little meeting we have.”

For the artist, the fight for liberation is an intimate story. Halaby herself was born in Jerusalem in 1936, and was forced to relocate to Lebanon with her family when she was just 12 years old. In the 1970s and 1980s, she was close with several artists who were members and supporters of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), and used their work as a form of protest. That sentiment, she said, runs through today.

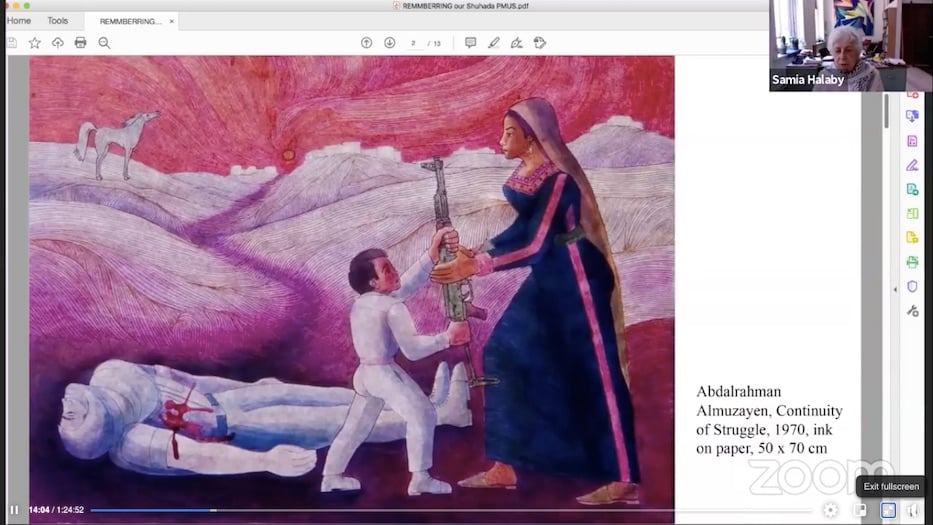

Halaby pulled up Abdelrahman Al Muzayen’s Continuity Of Struggle, noting that she was close with the artist and his contemporaries. In 1970, Al Muzayen drew the pen and ink composition as a sign of Palestinian liberation and revolution. It came over two decades after the forced exodus of Palestinians from their homes and three years after he formally joined the PLO himself.

It is not an uncomplicated image. A woman dressed in flowing blue and pink robes hands a rifle to a child who looks up at her. Pink, sunset-kissed hills stretch out in pen and ink, all the way to the horizon line. The child lifts his hands to willingly accept the weapon. Beside him, a man lies lifeless on the oxblood-colored ground. Blood seeps from a puncture wound beneath his rib cage. Further off, a horse raises its chin to the sky. The sky pulses with red and deep orange.

As Halaby let her image take over her whole screen, she broke down the symbolism of the work. A large, muscled horse symbolized Palestinian revolution, she said. There was a red sky for freedom. The weapon passed between mother and son was a legacy in the making. Against the backdrop, it felt like a fresh wound. Greetings in the chat, some from as far away as Egypt, had started to pour in as she spoke.

She pulled up a second image, this time a portrait of the author and late Palestinian journalist Ghassan Kanafani. Kanafani, who was born the same year as Halaby, was killed at 36 years old by a car bomb in Lebanon. During his young life, Kanafani chronicled Palestine’s 1936-1939 Palstenian general strike. His book Palestine's Children: Returning to Haifa & Other Stories is widely translated and still read today. Halaby said that she made the portrait after his death because he is, to this day, too often overlooked.

“Long live Ghassan Kanafani,” she said. “He is here surrounded by his fighters and co-defenders.”

Halaby pointed to other artists who continued his legacy, some using public art as a form of resistance. Among them, she said, was artist and avowed Communist Party member Abed Abdi, who worked with the Israeli artist Gershon Knispel on the sculpture Six Martyrs To The Day of The Land. Later in her presentation she returned to Abdi’s painting, to speak about his lifelong dedication to liberation work.

The monument pays tribute to the six Palestinians killed by Israeli police in March 1976, during a Palestinian general strike now known as Land Day. Held in the town of Sakhnin, the strike opposed the Israeli seizure and occupation of thousands of acres of land. Israeli police ultimately opened fire on unarmed Palestinian strikers, killing six people. Saturday, Halaby called the work “one of the most amazing sculptural monuments of the twentieth century.”

As she pulled it up, the timelessness of the piece extended beyond the screen, spilling out across computers across the country and the globe. When Abdi and Knispel completed the work in 1978, they proposed placing it in the middle of Sakhnin, where the hulking work would be a physical intervention on the landscape. Because “this was not allowed by Israel,” according to Halaby, the piece now stands in the town’s graveyard.

It struck a contemporary chord with one issue at the heart of last and this week’s violence—the proposed eviction of Palestinian families in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem, and wider attempts at ethnic cleansing from both the Israeli government and far right-wing Zionist groups including Lehava. As she spoke, Halaby channeled her own frustration at how enduring that history of displacement still is.

“And just as a thought here, it’s not that the U.S. looks away,” she said. “It’s that the U.S. pays for this consciously. It is looking very hard, and the U.S. is just as guilty as Israel in this holocaust that is taking place ever since the beginning of the twentieth century.”

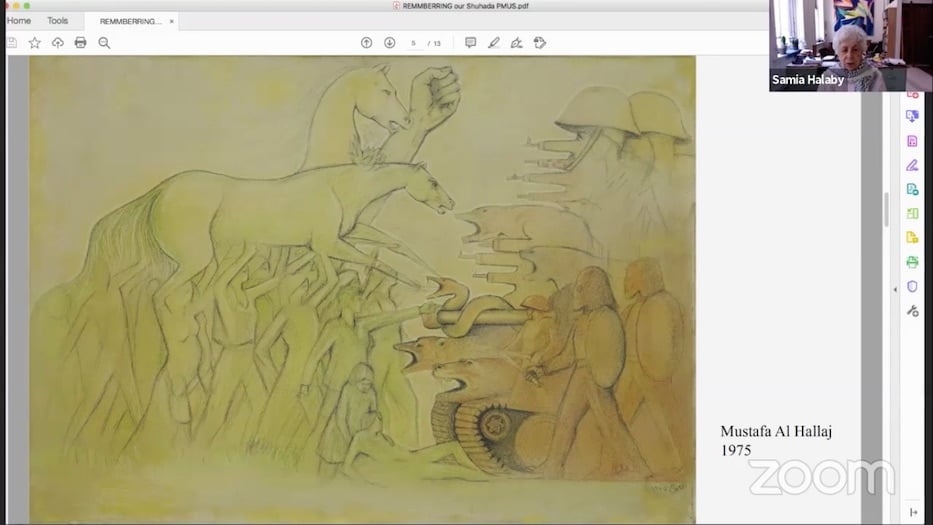

Halaby also noted the number of artists who saw—and continue to see—the issue of Palestinian liberation as tethered to the histories of African and Indigenous displacement. Born in Jaffa in 1938, Mustafa Al-Hallaj leaned on both Palestinian and African folktales in his work, using symbols that included the revolutionary horse and African HudHud bird.

Before Al-Hallaj’s death in Syria in 2002, Halaby spoke to him about the use of the Hudhud. Saturday, she started to weep as she recalled his reply. She explained that she was thinking of a friend, also a fellow artist, who had just lost a brother in Gaza.

“He [Al-Hallaj] said, the Hudhud is supposed to have buried his mother in his head, and that’s why he smells bad,” she said, her voice starting to break. “And he said, we Palestinian artists carry our fellow artists on our back.”

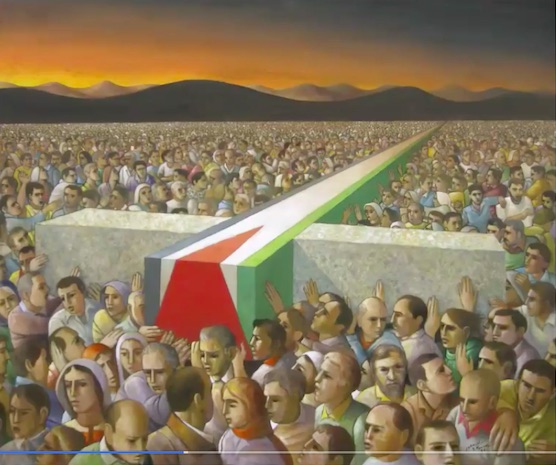

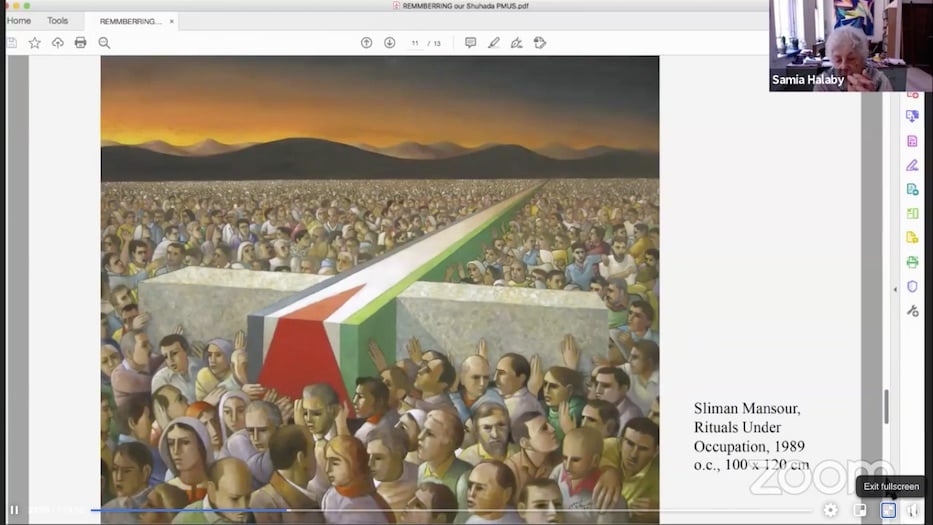

She traced a line from his work through the present day. From Al-Hallaj she jumped to Osama Said, Vera Tamari, and Abdal Raouf Shamoun, pushing attendees through art of the First Palestenian Intifada. She pulled up a 1989 image by “our primo artist” Sliman Mansour, showing thousands of Palestinians bearing a flag-draped cross, the weight of occupation. Like many of his contemporaries, Mansour showed the world how art can be explicitly political: he was part of a movement that stopped using Israeli art supplies in his work. Click here to hear him speak about his work as part of art week programming.

Halaby explained that the theme of the crucifixion—thought of as a Christian image—also became part of the revolutionary canon for Muslim artists. Before concluding, she flew through from the 1980s and 1990s to the early and mid 2000s, chronicling decades of violence committed against Palestinians. Halaby herself bridged past and present in 2012, when she began a series on the 1956 Kafr Qasim massacre.

“The spirit of struggle and fighting … to me, it is amazing that we are still able to struggle as a tiny national group,” she said. “We do have friends all over the world. And supporters. And they are growing. They just don’t happen to be the bourgeois governments of the world. They just happen to be the people of the world of goodwill. So to them, those who are our friends and demonstrating with us all over the world, our thanks and our friendship in return.”

“We Have Been Dying For Years”

Saturday’s opening remarks also included accounts from Palestinians on the ground in Gaza, as well as live footage from protests and demonstrations taking place around the globe. One individual chronicled a list of family members who have lost their buildings during the airstrikes. He later asked to have his name removed from the article for safety concerns.

“We came here last Monday, and war started breaking out on Tuesday,” he said as he spoke to attendees from a server room. They had been with their families less than 24 hours before Israeli forces raided the Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

Since he arrived, he said, the airstrikes have been a near-constant. He described evacuating buildings barefoot with his family, which he has now done multiple times. He said he was in mourning as he joined the conversation: he had lost a neighbor in airstrikes the day before. A building nearby, used to house people with disabilities, had also been destroyed.

“We didn’t really make it a few of those times,” he said. “But despite all of that, we’re very proud to be here. We’re happy to be here. I’m happy to be here with my parents and for my family during these tough times. Things have gotten to a really difficult place, where things are not moving forward. We have to stand up, and we have to resist and exist so we can change the status quo.”

He said that beyond rebuilding, his family and neighbors are concerned with their survival. In response to a question from Sha’ath, he described families moving from relative to relative, where they think might be most safe for the night. He spoke of homeless people living in tents erected on top of rubble.

Because the Israeli and Egyptian borders are largely closed—Egypt has reopened the crossing at Rafah for specific humanitarian cases only—he feels that “we are trapped.” When he speaks to family and friends, they “are alive, but they are shells” of the people he once knew. He said that there is huge stigma around mental health, post-traumatic stress disorder and ongoing shock.

“We have been dying for years,” he said. “What has been going on for the last few years is nothing called life. And people are sick of it.”

At the same time, he said, Palestinians feel united through their fear and pain. He does not know anyone who has not experienced loss—of property, of family, of home. He and his family have struggled to find potable water and watched as electricity goes out. He recalled driving to the server room, the only place he could find reliable internet, between airstrikes.

“We’re celebrating Eid despite all of this,” he said. “We’re mourning people and celebrating at the same time.”

To read the full schedule for Palestine Art Week, click here.