Downtown | International Festival of Arts & Ideas | opera | Arts & Culture | Arts & Anti-racism | Shubert Theatre | Yale Schwarzman Center

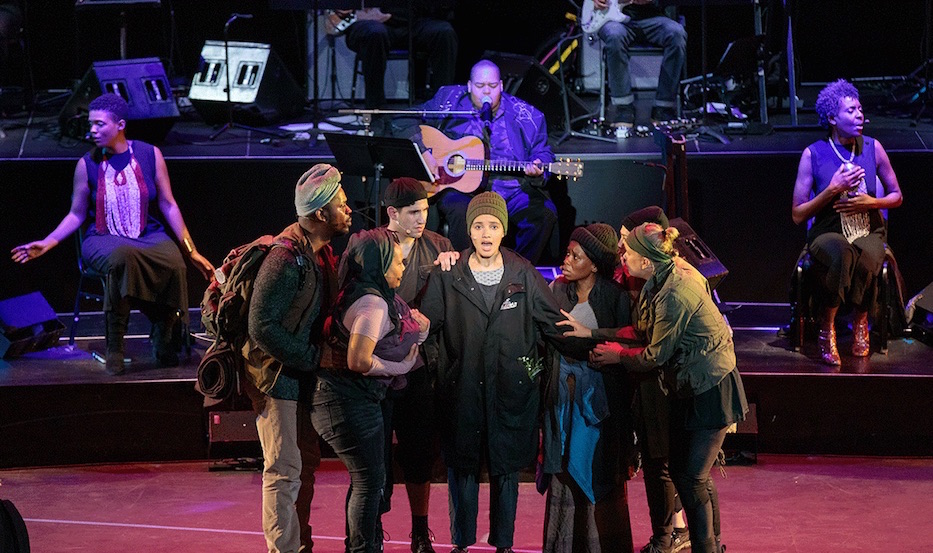

Reed Hutchinson Photo, courtesy the International Festival of Arts & Ideas.

The music cracked a body open piece by piece. First it was the question ringing out at center stage, a refrain of What you gon’ do? that hit listeners right at the sternum. Then the fear in the Reverend’s voice, lurking even as he promised God was listening. A violin rang out in the darkness, a full-chested wail, and listeners could feel the ground shift beneath their feet.

By the time Lauren Olamina (Marie Tatti Aqeel) appeared bathed in shadow and white light, the music had wormed its way into hearts and guts and bloodstreams, intertwined with breath itself. In every second of every note, the artist Toshi Reagon gave New Haven an offering.

Whether audience members took it when they left the theater was up to them.

On Tuesday and Wednesday night, Reagon graced the Shubert Theatre's stage with Parable of the Sower, an operatic adaptation of Octavia Butler's 1993 dystopian novel of the same name. Created by Reagon and her mother, Bernice Johnson Reagon, and directed by Eric Ting and Signe V. Harriday, the performance came to New Haven with support from the International Festival of Arts & Ideas and Yale Schwarzman Center (YSC).

It doubled as a culminating event for New Haven’s “One City One Read” program, which has included concerts, film screenings, discussions, and art exhibitions all dedicated to the novel.

In a six-month period that has seen escalating climate disaster, mass gun violence, flat-out denial of science and sweeping setbacks for reproductive rights, it became a two-hour masterclass in empathy, care work, mutual aid and trust building. From its first note to its last, it was also a breath-stoppingly-sharp reminder that another world is possible—if people want to work towards it together.

“Have you been taking excellent care of each other? Have you been taking excellent care of yourselves?” Reagon asked as she came onstage to cheers and applause from a full house. When the audience replied quietly, she shook her head and tried it again. “It is the only way we as humans are going to get through the next five, 10, 15, 20 years.”

The opera builds on the book—Reagon also folds in episodes from Butler’s 1998 sequel Parable of the Talents—but makes it clear that this is a source text, rather than a strict blueprint from which Reagon cannot stray. Published in 1993 and set in 2024, Butler’s Parable of the Sower follows 15-year-old protagonist Lauren Olamina (Aqeel), a resident of the walled-in Los Angeles suburb of Robledo. Outside Robledo’s walls, there is widespread climate disaster, violence, food insecurity and deep economic stratification. Inside, Olamina’s father (Jared Wayne Gladly) has kept the community together through a mix of aid and doctrinaire faith that Lauren increasingly struggles with.

As the book unfolds, Robledo’s defenses fall: violence descends on their community and she is forced to flee, essentially becoming a climate refugee in her own country. In other words, Butler envisioned in the last century what Americans are now seeing from victims of mass flooding, hurricanes, famine, wildfires, extreme heat, and cities that are literally sinking. Accompanied by Robledo survivors Zahra Moss (Be Steadwell) and Harry Balter (Noah Virgile), she heads North, forming the Earthseed Religion.

Along the way, her condition of “hyper-empathy” opens her to the extreme pain, suffering, and trauma of others. Or as a character says pointedly to her towards the end of the opera: “How many times have you died?”

It is a life-changing, uncomfortably prescient work of literature, adequate praise for and action from which Butler did not see during her lifetime. In the opera, Earthseed becomes a hook, as Reagon and two vocalists (in New Haven, they included Helga Davis and Shelley Nicole) belt out its fundamental belief system. All that you touch/You Change/All that you Change/Changes you, they sing. The only lasting truth/Is Change./God/Is Change.

This is also where Reagon makes magic. The artist, a folk musician who first premiered the work at New York’s Public Theatre in 2018, is much more interested in drawing on—and teaching from—Butler’s central themes of empathy, community care and necessary change than she is in providing an operatic recap of the novel. Sitting at the center of the stage Tuesday, she pulled out her guitar and began to play, watching as a half moon of benches filled with characters before her. Above her, a white fabric oval, broken at its front, made up the city’s walls.

Monique Brooks Roberts’ violin rose in the distance, so earthy it felt closer to its cousin, the fiddle. Characters greeted each other, united by the swelling music, and then were just as quickly pulled apart by it (when Aqeel sang “There’s a new world coming” and the ensemble joined in, a listener could feel it in their chest). Through all of it, Reagon’s libretto wove Black spirituals, gospel, rich orchestration, contemporary folk, and Americana into a sonic tapestry, so tight it was capable of taking a listener’s breath away.

It was as if Reagon had flipped on a switch that was in the audience’s universe, and also not in their universe at all. What makes Parable so timely, and also so terrifying, is that Butler could see a world that people are now living in, where corporate greed is killing the planet—and its tenacious, exhausted, often resource-stripped residents—and faith alone may no longer be a sufficient way to get through it. Around the stage, scenic designer Arnulfo Maldonado and choreography from Millicent Johnnie literally moved the work forward.

Through music, the work balanced the weight of belief with its precariousness. At one point, both Lauren and her mother (Karma Mayet Johnson) poked narrative holes in the Reverend’s steadfast preaching, only for her parents to share their love for each other as their world began to burn. At another, characters sang a rich, slowed-down version of “We Shall Not Be Moved” that had the audience at the edge of their collective seats, only for that peace to be punctured by reality. Whether they want to or not, a character noted, they would be moved. That’s the nature of climate change.

Nowhere was it clearer, perhaps, than the beginning of the second act, when Aqeel-as-Olamina appeared at the center of the stage, cloaked from the chest down in shadow. The light fell across her face and shoulders, making it look like she was enclosed in a space capsule or window (credit to lighting designer Christopher Kuhl). Her voice clear and deep, she sang out into the total darkness. Has anybody seen - my father? She asked, and suddenly all the buttressing and narrative of act one melted into her terror and grief. It hung in the air long after she had finished, and it was clear that the walls of the city had fallen for good.

Within the performance, Reagon continually reminded the audience—and the cast and crew—that they would fail without mutual care. Several of the works in the opera invite and request audience participation, from clapping to keep the rhythm to singing along. During her song “Olivar,” a ballad against corporate greed and modern-day enslavement, Reagon asked the audience to join in on the chorus. The Shubert filled with sound, some attendees hearing each other for the first time.

At another point during the first act, she herself broke the fourth wall, stopping the show so gently that it appeared to be part of the opera. An actor’s microphone had been left on, for what she said was the first time in the show’s multi-year run. Reagon looked around for the source of the sound, and then started talking to the audience, the actor, and her sound engineer all at once.

“Yes baby your microphone is on, you need to stop talking,” she said with the same cadence that she might to a child who had just asked for a glass of water.

“Thank you Octavia,” she later said, “For telling us that we in the moment all the time.”

These melodies have a life beyond Parable’s libretto: they are a template for understanding the world and a body’s place in it. And no wonder: Reagon’s mother and co-creator, Bernice Johnson Reagon, is a composer and founder of Sweet Honey in the Rock. Her grandfather was a founding member of The Freedom Singers, whose music became part of the soundtrack to the civil rights movement. It is impossible to listen to Reagon’s “Olivar” and not hear a warning that Sweet Honey issued decades before, as they wrote collective care into their body of work.

When the lights went down, audience members had a choice: to take Reagon’s lessons, and Butler’s, or to leave them. During Reagon’s synthesis of dystopian fiction, modern-day enslavement and corporate America, it was difficult not to think about the $43 billion corporation up College Street, or the displaced people on whom Steven Schwarzman made enough money to have a university arts center named after him. When Lauren headed North dressed as a man, it was a reminder to share resources and shake off the scarcity mindset. It was, in music, what groups like the Black Infinity Collective, Semilla Collective, and the New Haven Pride Center have been doing for years.

While Parable envisions mass disaster, Reagon has given the audience a gift, reminding members of what they can achieve with and through a focus on collective liberation. By the end of the play, it was not just Butler’s words (her call to “choose your leaders” in Parable of the Talents feels particularly timely) that hung in the air, but also Reagon's. There is a new world coming. Whether New Haveners choose to meet it is entirely up to them.

To listen to a conversation between Toshi Reagon and WNHH Community Radio host Babz Rawls-Ivy, click on the audio above. WNHH Community Radio is one of the Arts Paper's content partners.