Books | Poetry | Poetry & Spoken Word | Arts & Culture | COVID-19 | People Get Ready Books

| Lauren Anderson Photos. |

It's National Poetry Month. And just because we're physically separated doesn't mean we can't read together.

More than two decades ago, I was an anxious undergrad in a then-legendary course at Yale University called Daily Themes. Its terms of engagement involved extracting from our not-yet-fully-formed prefrontal cortexes a piece of creative writing every day.

To nurse this along, there were prompts of varying specificity. Wracked by insecurity—that sense, which has never left, of certainly being an admissions error—I wrote drivel and sweat through each session, wanting and not wanting my words to be among those selected for reading by the course’s instructor.

My writing was read aloud just once that semester, and I knew before it happened. It was one of the only times in college I recall feeling proud. I had produced a page or two so sincere it hurt. It captured something I recognized even then, despite naivety and jangled nerves, as a sparkling snapshot of the greatest possibilities that a place like Yale affords.

It was about an exchange between my big-headed blond baby brother, then a high school senior, and my roommate, whose Korean immigrant parents brought us all manner of NYC swag, including seasoned seaweed and crates of clementines.

My brother, like me, had never seen such small oranges before being casually gifted a few in the regular course of a dorm room evening. If I close my eyes, I can replay it: my roommate's calm manner, her sweetness toward this oversized boy, her slim piano fingers showing his clumsy digits how to unwind a rind into a single curl.

I can feel the weight of her light, light touch, the way my brother looked up bashfully through bushy brows at her, perched crane-like on the arm of the couch. What makes a man a gentle giant in this violent world? These little things, these small debts.

My T.A. that semester was named Stephen, a graduate student, bird-boned and kind. Nevertheless, I was terrified. I remember dreaming up all manner of fantastical excuse for missing our meetings. I also remember not having the courage to actually deploy any of them. I would walk weekly into that dingy, loved coffeeshop, long since gentrified out of existence, wishing its floor would swallow me whole. I knew Stephen’s time had far better uses.

But I also felt, for the first and only time at Yale, like I was a disappointment in a way that mattered. Stephen seemed quietly sure I had it in me somewhere to do better. Someone was rooting for me. Even though I couldn’t muster my way out from under all that anxiety and cliché, Stephen never grew any less disappointed, never adjusted expectations down to the level of my performance.

The mark-making continued - a trite phrasing circled, a useless alliteration crossed through, a question mark, a ‘why?’ It seemed to implore, “stop trying so hard; why not be yourself?”

When the semester ended, I was crestfallen that I hadn’t been able to deliver. Then Stephen gifted me a collection of Robert Pinsky poems, still on my shelf, and a different poet to each of the other five or so students. It was a defining moment in my education. Despite how terribly I had written, this kind, smart person still thought I was worthy of poetry. It floods me still with a gratitude that I find hard to convey – the same kind of unspeakable gratitude that made me duck into my dorm bathroom to weep while Erica and Evan giggled together over the bitter film that peeling citrus fruit left on their fingers.

I ended up a professor. I’ve managed some success, but it’s a job to which I remain ill-suited. It feels a lot like Daily Themes did all those years ago. I know what I’m supposed to do, but I can’t seem to find my authentic self in doing it. I dream up fantastical excuses that I never deploy. I frequently wish for that swallowing floor. In the process, my patience with myself has worn thin. I have wondered, more than once, who am I if I still cannot find myself fully? Where is the oft-promised confidence of one’s 30s and 40s? Where is the ease and sense of competence that is supposed to come from a decade of work?

Poetry has kept me afloat when floundering. It started when I signed up for an intervention via my inbox. I realized with sadness that I had stopped doing things I love, like reading for pleasure. I started books, but didn’t finish them, in part because work seemed to expand into every crevice of life. What could I hold myself accountable to reading for no reason other than loving myself enough to do it?

I decided I could manage at least a poem each day. It seemed a reasonable and forgiving starting point. If I skipped here or there, I could restart without the implicit failure associated with having stalled in a book—forgetting where I’d left off, trying in vain to remember, paying overdue library fees.

Poem-a-day was habit-forming almost immediately. Some poems I hated and discarded quickly. Some I loved enough to linger on. When I came across one that I couldn’t let go, I started a virtual folder called “Poems I Like.” It began to fill and with poets I had never before read. I decided to purchase a volume every month by someone in the file.

With time, I became more methodical. I read a poet’s works in chronological order, and I found that I loved the approach. So I read everything Ada Limón had published. Then everything by Matthew Olzmann, whose poems led me to Czeslaw Milosz. Vievee Francis visited the residency where my partner was painting, and he bought me her collections. I devoured them, and delighted in realizing only via inverse dedications that she and Olzmann are partnered for life.

I read Jamaal May, because both mentioned him in their acknowledgments. I read Ross Gay. I read Terrence Hayes. I read Reginald Dwayne Betts. I read everything by Tiana Clark, twice. I felt something shifting. I was coming unstuck, vibrating at my edges.

I decided I would take more seriously a dream I’d long quashed—namely to shepherd into existence a community bookspace with new and used books, including lots of poetry. Knowing nothing about how to do this, I applied for a bookselling job in a well-known bookstore some distance from home. It made zero financial sense, and yet it became my second best decision in years (the first was poem-a-day).

As it turns out, being around books and other people who take time to talk about them was a balm on sores I had let fester for years. For many people, it must sound odd to hear a professor say that it took a minimum wage bookselling job to re-center reading, but I know plenty of colleagues who understand why this might be. Don’t get me wrong. I’ve always read a lot for work. And I’ve always spent lots of time talking about reading. But not in the particular ways a bookspace encourages.

I’m sure knew intellectually what galleys were, and yet I was giddy to the point of high when I realized that bookselling meant I would get to read things, in advance of other people, for free. When a colleague gifted me my first “advanced reader copy,” which she left in my mailbox because she thought I’d appreciate it and write a respectable “shelftalker,” I nearly cried. The gesture was so specific and spot-on. It depended on being known in a way many people don’t ever know each other.

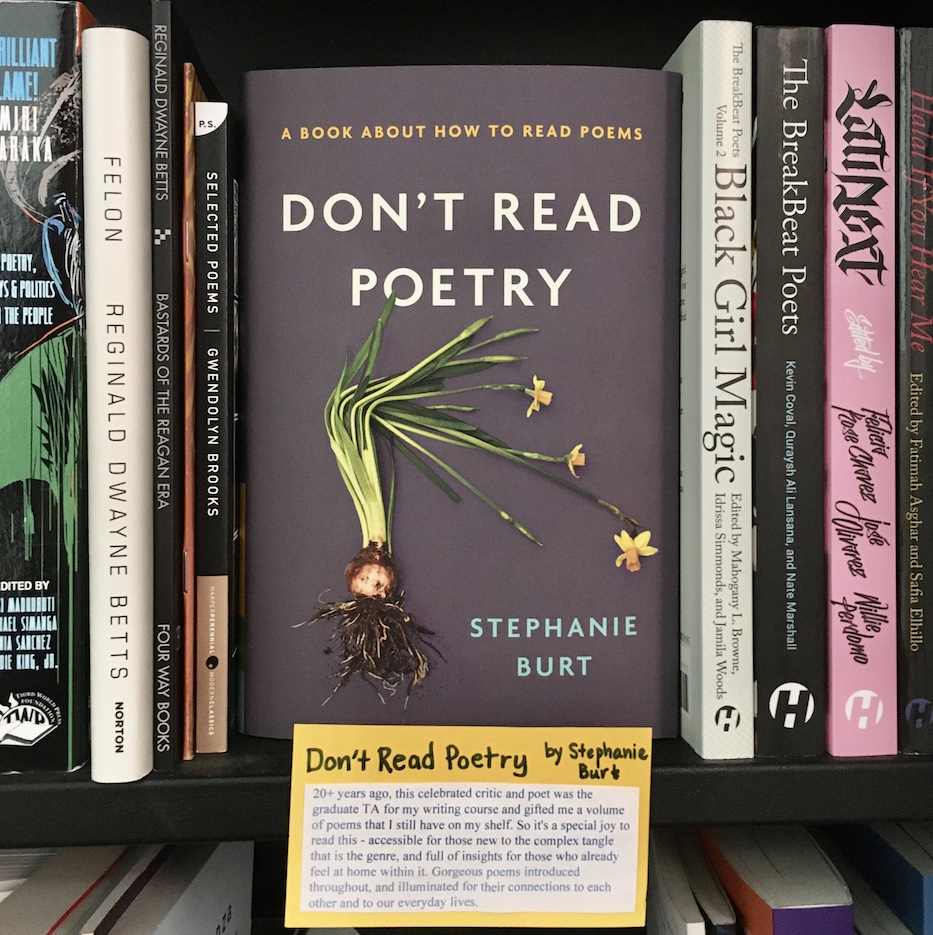

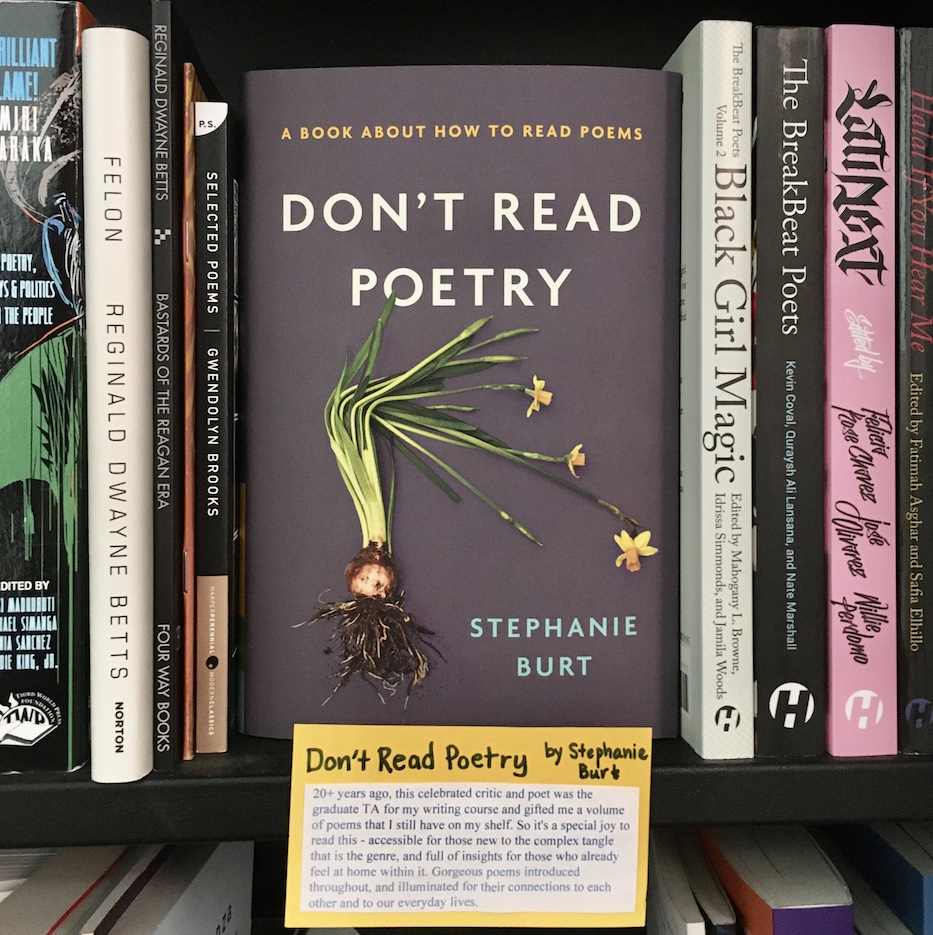

That book she gave me was Don’t Read Poetry by Stephanie Burt.

Almost immediately, the author’s name struck me as familiar somehow. I flipped the book over to read the back cover. I tried to recall the last name of my long-ago T.A., who I knew from internet searching years before went on to become a celebrated literary critic. Wasn’t it Burt? “Maybe they’re related,” I thought. And then I opened to the back pages, and there she was, Stephanie, exuding that same brilliance and calm kindness. That moment of recognition was transporting; the sense of appreciation, joy, and synchronicity transcendent.

I read the book cover to cover in a few days. Somewhere in the middle, while working an evening shift at the bookstore, a guy in jeans and hoodie bopped by, looking for something. He met my gaze and asked for the poetry section. I responded with nerdy glee and walked him over. I asked if he was a poetry reader. He said yes, and that he wrote, too.

It sounds corny, but I’m pretty sure I actually said, “thank you for putting poetry into the world.” He pointed to the shelf where his book might have been but wasn’t, told me its title, that he was in town for a poetry conference. He asked whose poems I had been reading. Some I mentioned he knew personally. He complimented my selections, and asked if I’d like the one remaining copy of his book that he had in his car. He walked out, and back in, joking that only a poet comes to a bookstore and ends up giving his book away for free.

Then he wrote the most delightful inscription and invited me to come to his and a fellow poet’s reading the next morning. When he left, I opened the book to find a poem I had saved months before in my “Poems I Like” folder. On the way home, I called my friend and bookspace co-conspirator, Delores Williams or Dee, and asked if she wanted to cancel our morning commitments and sneak away to a poetry reading by the sea.

It was an easy sell and a cosmic fist bump. We slunk in and took seats in a not-nearly full room. I opened the conference program to find that Tiana Clark had read the day prior. Then she walked in and took a seat nearby. Sean Thomas Dougherty, the generous soul from the bookstore, read beautifully. So did Adrian Matjecka, Indiana’s poet laureate. Afterwards, Dee nudged me up to Tiana, who—upon hearing I’d borrowed I Can’t Think About the Trees Without the Blood twice from the library already—sweetly opened her suitcase to inscribe the last copy she had on hand.

We spent the next hour in a sprawling conversation with Martín Espada about bilingual education, poetry, and our dream of creating a bookspace where we can be these versions of ourselves—giddy from reading—and hold space for others to do the same.

When it ended, Dee and I sat on a bench by the sea, holding hands like we used to with friends when we were little, reveling in the poets’ blessings, and taking pictures of our feet—mine in combat-ish boots and hers in sandals—dangling over sand and backed by wide blue. We promised each other that we would do the brave thing that excited and scared us and that these wonderful word-workers somehow thought we could make real.

I thought of Stephanie then. I don’t think I would have ever picked up poetry and believed it was for me if she hadn’t gifted me that slim volume, Pinsky’s History of My Heart, in 1998. Somehow it meant all the more given how unimpressive, clunky and inauthentic I had been as a writer.

When someone has every reason to dismiss you, but still finds you worthy of something as profound as poetry, it can’t help but stick. That doesn’t mean I’m comfortable with myself, or even with writing this. But I am becoming more of both. That is life’s project, isn’t it?

Now months ago, when I was writing out the shelf-talker for Stephanie’s book, a woman in her 80s approached the counter. She was so quiet I didn’t see her until I looked up. She asked what I was writing and so I told her about the book and how it was special to me because the author had given me my first real volume of poems. This delighted her. She told me she had once loved poetry, excelled at “elocution,” and hoped to return to reading poems.

She asked about Stephanie’s, and I explained that some were under the name Stephen. “Isn’t that wonderful?” she said, her eyes twinkling under her white pixie cut. “That people today can be who they are supposed to be.” She insisted that I must write to Stephanie “to tell her that she is remembered, that she had an impact, that you still read poems because of her.” We took a picture to send along with my message.

And so here it is, and here I am, writing against discomfort, in public gratitude to all the poets and generous teachers, and to one of them in particular. Thank you, Stephanie, for all the poems.

We all need poetry—perhaps especially now, mid-pandemic—and we deserve it. There are poems out there waiting for you; I believe that. To paraphrase a favorite by Sean Thomas Dougherty: someone has written words in the exact shape of your wounds and, I’d argue, your hopes and dreams, too.

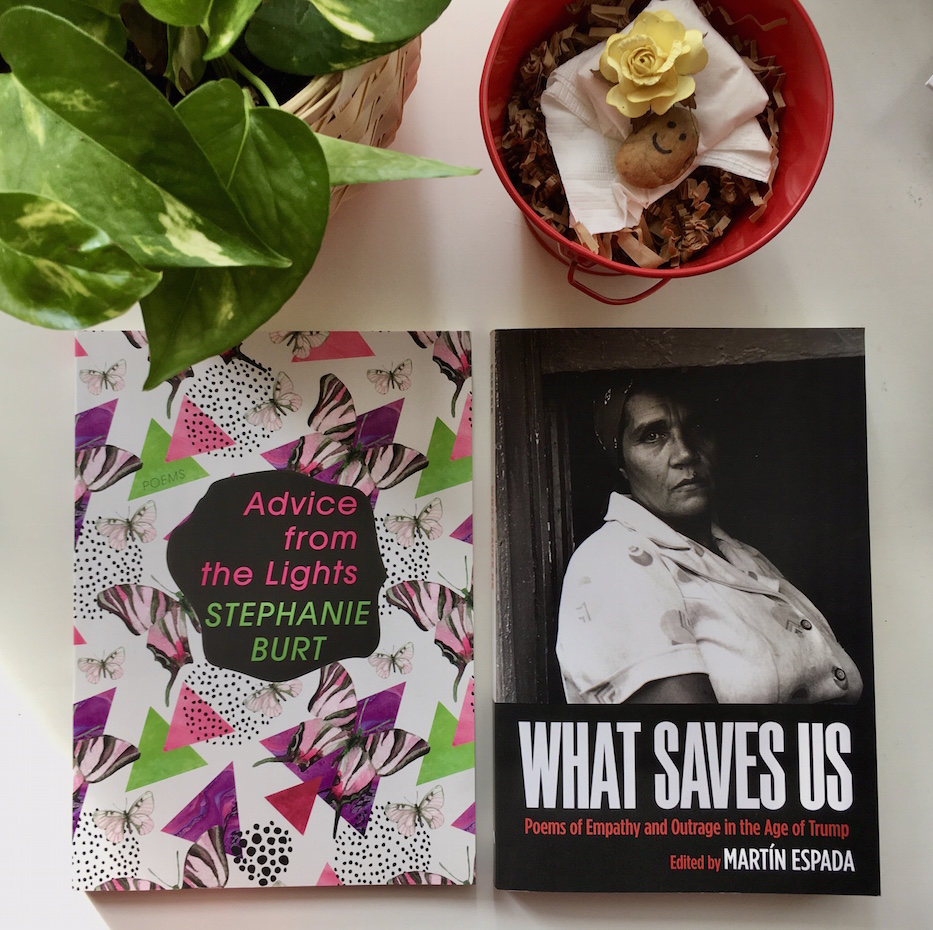

If you’re not sure where or how to start, what better bridge between March’s finish—International Transgender Visibility Day and the last day of Women’s History Month—and April’s start than Stephanie’s luminescent collection, Advice from the Lights?

“Part nostalgia, part confusion, and part ongoing wondering: how do any of us achieve adulthood?” it is this year’s selection for the NEA’s Big Read, and so the International Festival of Arts & Ideas has free copies to distribute, which I’ll happily deliver by bike to your New Haven doorstep upon request.

You’re also invited to join People Get Ready as we make our way, with the help of community members city-wide, through Martín Espada’s timely titled collection, What Saves Us: Poems of Empathy and Outrage in an Age of Trump.

And if neither of these is your particular cup of tea, perhaps a special teacher in your life can help you find precisely the soul-soothing poems you need.

Lauren Anderson is a New Haven resident, literacy professor, and co-founder of People Get Ready.