Politics | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Yale Center For British Art

| Richard Hamilton, Kent State, 1970, screen print, Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Barbara Sunderman Hoerner. |

The blurry outline of a body stretches across the center of "Kent State." Smears of blood on the person’s face, chest, and arms give the screenprint a sinister quality despite its abstract nature. Captured by Richard Hamilton on his Hasselblad camera, this image originated from a televised report of the Kent State University shootings on the Ohio campus.

Hamilton’s mediated work—a precise shot of a fuzzy television screen depicting a dead body—is both the largest and most demanding work in the exhibition, Peterloo and Protest. This piece shows the aftermath of a protest that turned violent, echoing the outcome of the Peterloo Massacre.

The exhibition, now open at the Yale Center for British Art, runs through Dec. 1.

In total, 30 objects culled from the museum’s collection have been brought together on the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre for this exhibition. On Aug. 16, 1819, around 15 people were killed and hundreds were wounded in St. Peter’s Field, Manchester.

Pregnant women and children were purported to have been among the victims. As a volunteer cavalry attacked an unarmed crowd—estimates range from 60,000 to 80,000 people—more troops were called to the scene. What began as a peaceful demonstration ended in a bloody political melee.

%20Deluge,%201848.jpg)

| Print made by John Doyle, The (Modern) Deluge, 1848, lithograph in tan and black ink, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. |

The fallout from this day was monumental. Within two years, John Edward Taylor, a journalist whose firsthand experience of the 1819 protest contrasted with the media’s portrayal, founded the newspaper Manchester Guardian. Increased awareness of class consciousness led to the formation of trade unions. After a string of riots, the Great Reform Act of 1832 passed into legislation, introducing positive changes to the corrupt British electoral system.

Responding to the tragedy, the English Romantic Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote The Masque of Anarchy published over ten years after it was penned. Shelley’s poem expounded on the consequences of the uprising, emphasizing the iniquity between a tyrannical government and its citizens.

The exhibition’s wall text states that lines from this poem surfaced during the 1989 student-led protests in Tiananmen Square as well as in Cairo’s Tahrir Square during the Egyptian Revolution of 2011.

| Print made by George Cruikshank, A Scene in the New Farce–as Performed at the Royalty Theatre!, 1821, hand-colored etching, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund. |

Documentation of either incident within this exhibition would have cemented the continued relevance of Shelley’s text and illustrated the lasting impact of the Peterloo Massacre. Instead, curator Lars Kokkonen has focused on the events surrounding the Peterloo Massacre—immediately before and following the rebellion—as well as protests from over a century later.

Many of the works in the show set the scene for viewers: Portraits of prominent political figures such as Robert Banks Jenkinson and Henry Addington give faces to those responsible for the atrocity.

An 1820 lithograph from an unknown artist pinpoints where a group of conspirators who had planned to assassinate the prime minister, Lord Liverpool, were found. Yet whatever historical insight these artifacts provide, most fail to inspire a viewer’s examination of the role or merit of protesting.

| Lewis Morley, Tariq Ali and Vanessa Redgrave, Anti-Vietnam War Demonstration, London, 1968, gelatin silver print on semigloss photographic paper,Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Dr. J. Patrick and Patricia Kennedy. |

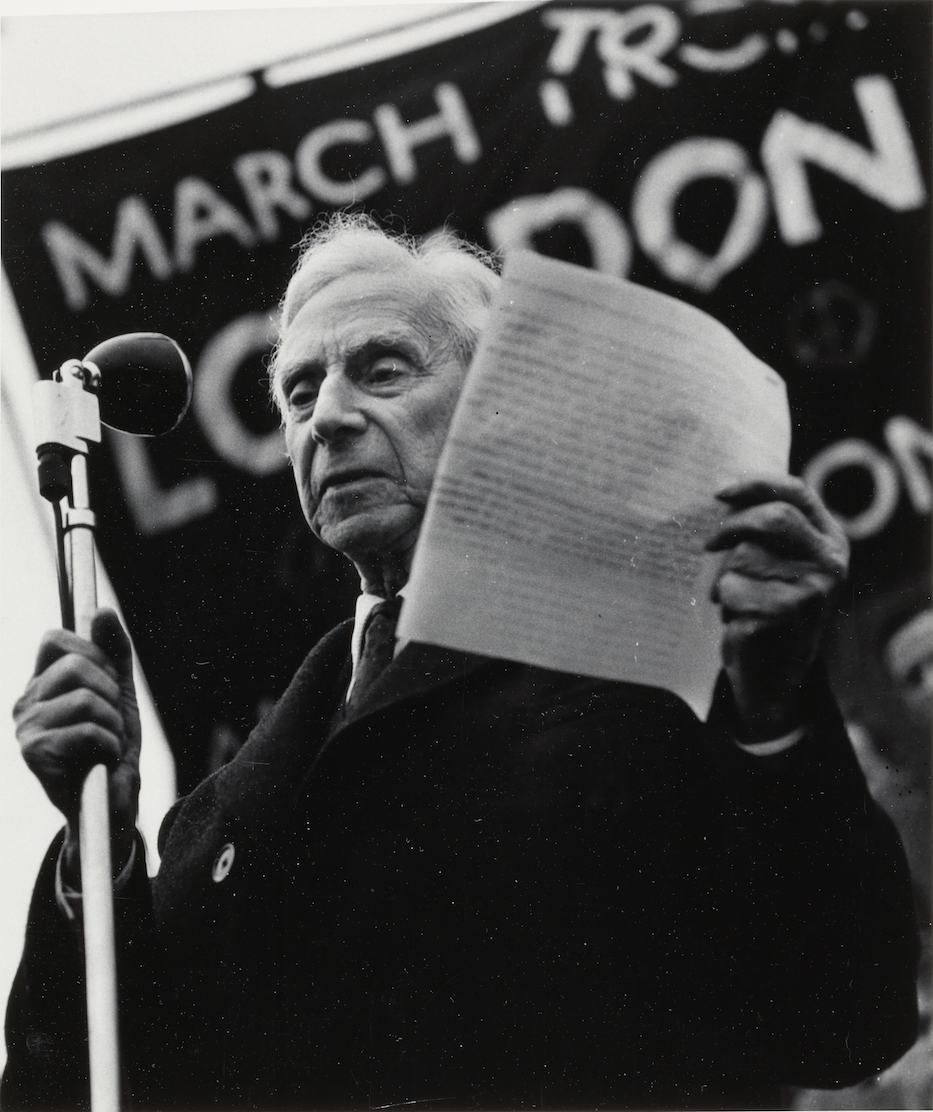

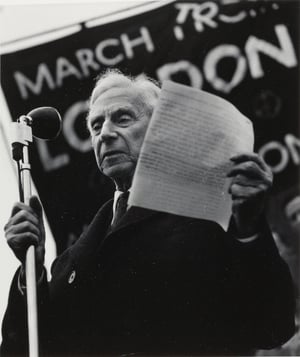

More compelling are the works in this exhibition presenting protesters from the Vietnam War era such as the aforementioned work by Hamilton. Lewis Morley’s photographs of various demonstrations in London on occasion feature familiar faces—movie star Vanessa Redgrave, philosopher Bertrand Russell, for example.

In a photo from March 1968, activist Tariq Ali stands next to Redgrave, who has donned a white headband worn at Vietnamese funerals. After this protest, Ali published an issue of Black Dwarf, reviving the radical newspaper that was circulated around the Peterloo Massacre. In both instances, Black Dwarf was intended to foment political action.

Political texts notwithstanding, the connection between the Vietnam War and the events of the Peterloo Massacre seems flimsy without a more expansive examination of protests throughout British political history. Why aren’t there greater examples of protesters and political demonstrations that span a broader timeframe?

The advancements of the film camera compared to printing techniques augment the distance between the two events. While the Vietnam War protesters are captured on film, the works relating to Peterloo are reproduced as prints. These documentary photographs lend themselves to veracity, while the prints are aligned with the agenda of the 19th-century artists or patrons.

In Peterloo and Protest, the timeliness and title bring a sense of anticipation to this compact show. Yet a more comprehensive study of protest imagery could have made clear the importance of protesting as an integral tool for social change.

Given the current—and contentious—state of British politics, the conceptual crux of this exhibition is powerful, but the execution seems superficial, thwarted by the limits of the collection. Overall, Peterloo and Protest misses the opportunity to tie the cultural and political aftermath of the Peterloo Massacre to the present.

Peterloo and Protest runs through Dec. 1, 2019 at the Yale Center for British Art. To find out more about the gallery’s hours and collection, visit its website.