Music | Poetry & Spoken Word | Arts & Culture | The Hill | Arts & Anti-racism | New Haven Adult & Continuing Education Center

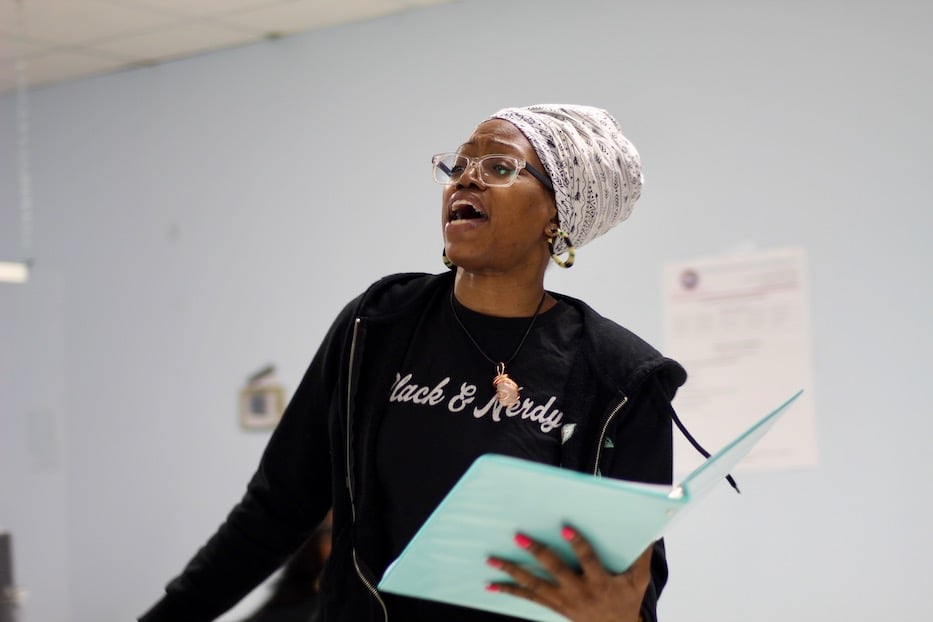

Lyrical Faith during the performance. “When everything goes into flames, everybody looks to the artists," she said. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Lyrical Faith was somewhere between Gun Hill Road and the Manhattan College Parkway, charting a course through the Bronx in her mind. In one universe, her feet click-clacked down the sidewalk, surrounded by sound and color everywhere she turned. In another, four dozen pairs of eyes watched her every move.

Back on Ella T. Grasso Boulevard, twins Jada and Janada Colon listened carefully, hanging onto the story of a borough that was once their home.

Thursday morning, Lyrical Faith was one of four artists to ring in Black History Month at New Haven Adult & Continuing Education, during a celebration packed with spoken word, music, and a cheer- and snap-filled talkback. Organized by High School Credit Student Support Specialist Mike Twitty, the performance brought in over 50 students for an hour of poetry and drumming.

In addition to poets Lyrical Faith, T’Challa Williams, and Tarishi “Midnight” Shuler, the event featured drummer Albear Sheffield, who is an alumnus of the program. In every moment, it was a reminder of the talent and weight of words, and their ability to hold the world together even as it burns.

Or as Lyrical Faith said, “When everything goes into flames, everybody looks to the artists.”

“Art being an access point is my whole jam,” she said in a conversation after the performance. “It’s a way in. They see this, and they feel like, ‘I can do this.’”

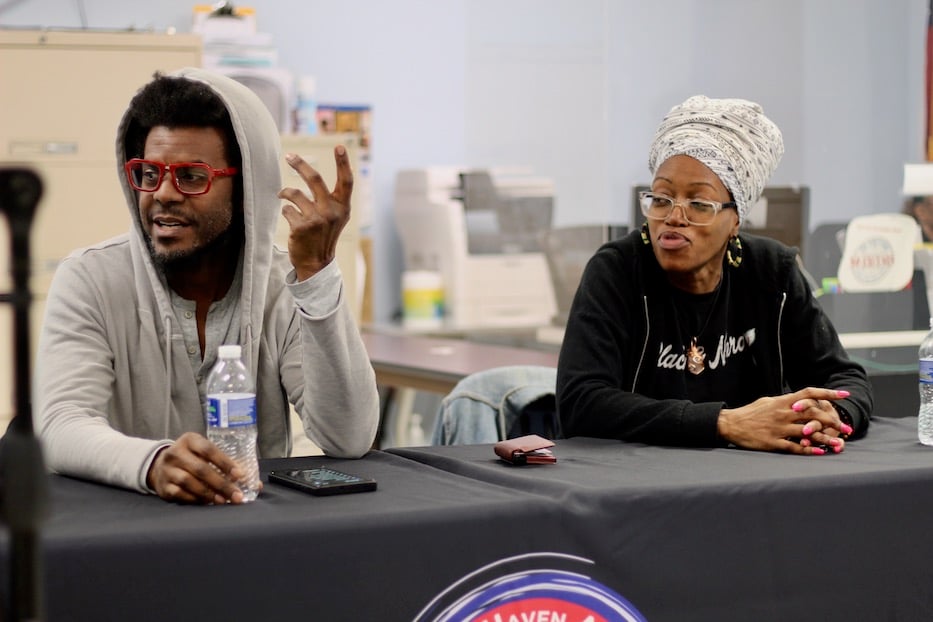

T'Challa Williams.

From the moment poets took the mic, they transformed the blue-walled room into a stage, their words weaving whole worlds out of thin air. Coming to the front of the room with a roar, Williams looked around, then cracked open a mint-green binder that nearly matched her jeans. Her eyes danced from the page to the room back to the page, picking out the right poem in seconds.

Sidestepping the microphone, she spoke straight from he ribcage.

“I will bite the hand that thinks it is feeding me/Like my life ain’t no seed/You’ve been harvesting,” Williams read.

Extending one hand as the other kept the binder steady, she traced a path from the theft and enslavement of Black people and Black histories to centuries of oppression and economic disenfranchisement to the present, when police are still killing Black people at routine traffic stops, convenience stores, and in their own homes.

“My people/Will be/Free!” she exclaimed defiantly. “See free! Taste free! Speak free! Freely confidently free—”

“Come on now!” a voice urged from somewhere in the middle of the audience. More voices joined in, encouraging her.

“Confidently free!” she continued. “Cre-a-tive-ly free! Mentally free! Physically free! Spiritually Free! Sex-u-ally free! Financially free!”

Snaps filled the room. She imagined a world where state-sanctioned violence no longer existed. She spit into being a place where people cared more about the loss of human life than the potential of property damage. She willed attendees to vision a country where the 1619 Project was not so immediately contested, because people understood it was history.

Here, between words and breath, was her framework for a liberated future. When she finished, the space exploded into applause.

She paused to take a few sips from her water bottle, then looked back at the audience. “Y’all hot?” she said. “I’m hot.”

She turned to her poem “Impossible Mission Force,” bringing that future back into focus. Looking to the unrest of the past three years—and the past four centuries before that—she challenged listeners to take action on a grassroots level, making change in their own communities instead of behind their screens or at a single action.

“The immediate change you can impact is right where you be,” she read, raising one hand over her head. “Join a committee. Take that hot air from the metaverse and transmute the energy to where it can be fully of use./We must sweep our own stoop.”

She critiqued a constant, churning media cycle that shuts down Black bodies and Black dreams. In the same stanza, she gave the antidote: listeners could believe in hope as a form of resistance. They could dream as a form of resistance.

“Tom Cruise that shit!” she read to laughs and a few cheers. “Ethan Hunt this bitch! Hope is not a strategy my behind!”

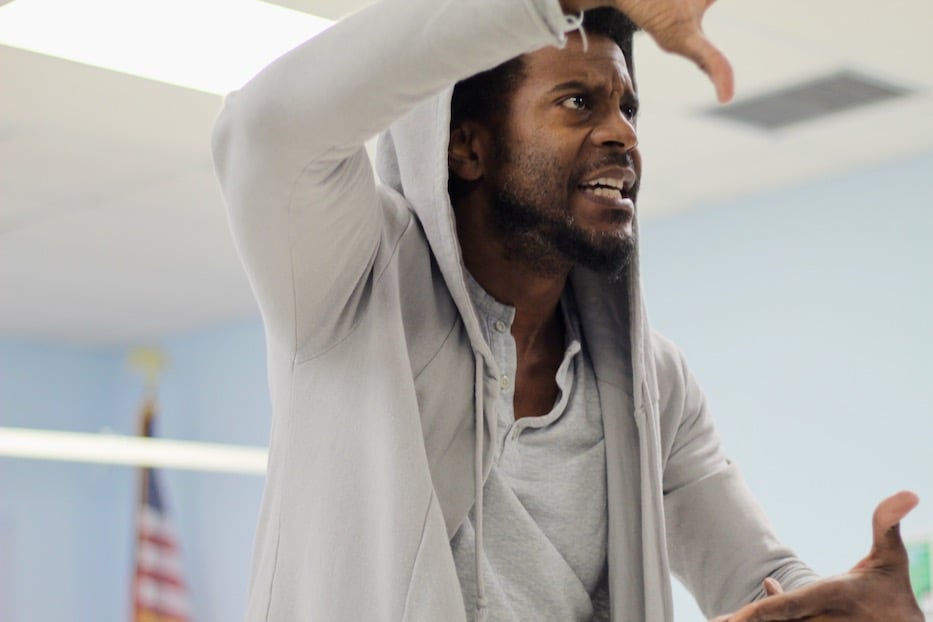

Shuler during his poem "The Photographer."

That fire ran through the end of her performance, the room transformed into a sizzling stage. When Shuler took her place, hands flitting through the air, he looked out at dozens of wide-eyed faces and smiled. While he now lives in Meriden, the artist grew up in New Haven and serves as the interim director of The Word. This was a hometown crowd.

He encouraged attendees to let themselves speak back to the poets, in a style of call-and-response that separates spoken word and slam poetry from buttoned-up readings. Minutes later, he would show off his own rule, slipping a laughter-edged “Don’t Be Nice!” in between two of Lyrical Faith’s pieces.

After warming the audience up with his poem “The Photographer,” he paused for a moment and took an informal poll of the audience. How many people, he asked, had gotten called a name that was not theirs? Over a dozen hands went up around the room, some students audibly mmm hmmm-ing as they raised their arms toward the ceiling. Shuler nodded, and went right into his poem.

“True story,” he started, his palms cutting through the air. When he was born, Shuler’s mom wanted to name him Kunta Kinte, in honor of the release of the film Roots that same year. His aunt pushed back, and suggested Tarishi. In Swahili, the name means messenger. He later said that he did not know the origin or the meaning of his name until he was in his 30s.

“I guess my family wanted to give me a name/That would remind me/Where I came from,” he read, hands always in motion. “We live in the generation that gentrification/Had some people bleaching their skin/So they could forget their next of kin were Africans.”

He jumped from the meaning of his name to the creation of race and racism, the theft of both people and land for the idea of America, the historic and continued oppression of Black people in the U.S. He peeled the years back from 2023, until listeners were sitting with a much younger Tarishi in a middle school classroom. He set the scene, in which a classmate insisted that Tarishi was too difficult to pronounce, and said Hershey instead.

“I should not allow/Someone to easily marginalize my life to fit inside boxes of chocolates,” he read to snaps. “If we can allow our English teachers to colonize our tongues, so we can speak/Stanislavsky/Leonardo Da Vinci/Sikorski/Learn how to say/Tarishi!/It’s easy!”

In front of him, the room was alive. Snaps and cries of yesssss bubbled up. Energy popped and crackled. Here was the reclamation: not just for Shuler, but for many of the students in the room, and thousands of people outside of it, too.

He broke down the seven letters in his first name, his fingers popping from his palm. When he called it “an acronym for Trans-Atlantic-Refugee-Individually-Seeking-Human-Independence,” the room went wild. He rounded a narrative corner, refusing to be silent or misnamed as he raised his voice, and the energy stayed with him.

Before the end of the morning, he would bring that same verve to a number layered with music and warning to aliens not to come to planet earth, unless they wanted to experience racism for themselves.

So too for Lyrical Faith, who brought the house down when she performed last month at the 27th Annual MLK Jr’s Legacy of Social & Environmental Justice Z Experience Poetry Slam. Stepping up to the microphone after a performance from Sheffield, she conjured New York City, paying homage to the cacophonous and always-moving streets of the city that raised her. As she read, eyes locked with every pair in front of hers, she brought listeners into her version of the city.

Suddenly, New York City felt intimate, its 302 square miles melting away. Faith pulled the audience down sidewalks crowded with the joyful noise of street vendors and conversion crackling with energy, into subway cars filled with young dancers and old musicians, into a borough “with more bodegas/than streetlights” that made her feel instantly at home.

“I can be far away from home but still feel like I’m next door to the Barclays/Or the NuYo,” she read, a smile creeping across her face as one hand fluttered to her chest and let a finger rest there, over her heart. “My city is every movement from the Nuyorican to Stonewall to hip-hop to the Renaissance …”

She mourned with the bootleg DVD vendors who lost business as streaming services rose to prominence. She celebrated movie premieres with Black audiences and Black protagonists too, where a theater was full of noise and nobody complained. She defended New York as a city of survivors and strivers, placing her body between its five boroughs and the whole world.

Standing in sunshine-yellow heels, she carried that same brisk momentum from audience banter (“Karens are out of control,” she said after telling a story about a white woman who called the police on her in Manhattan, as she was waiting on Triple A for assistance) to her slam-shattering “Black Poem” to Sheffield’s second performance, in which all three poets pulled out their phones to film another artist in action.

As a backing track coasted over the room, Sheffield eased into a groove, his drumsticks bouncing as his feet worked the pedals beneath him. He raised his arm, and folded in the tinny whisper of the hi-hat and rumble and thump of snare drum. When he turned to face the audience, he burst into that deep, meditative kind of smile, eyes closed as he cocked his head to one side and kept playing.

“Run that back!” yelled a student in the second row when he finished. Sheffield followed the sound, and beamed at her.

Students Jada Colon, Amina Brown, and Janada Colon.

In an interview after the performances, 18-year-old twins and Adult Ed student Jada and Janada Colon said they were inspired by the performances. Raised in the Bronx—"I felt her a lot,” Jada said of Lyrical Faith’s performance—the two both moved to Bridgeport about five years ago, and began

“It’s freedom, independence, just being you,” Janada said of Black History Month. She added that she prefers Adult Ed to her previous high school, Harding High. “We like the opportunities better.”

“It was very inspiring, and the way they explained their point was different, and the way they expressed themselves,” chimed in Amina Brown, who grew up in Manhattan, and moved to New Haven two years ago. For her, she added, Black History Month means “Black freedom, Black empowerment. I’m Black 100 percent of the time. All through [the year].”

Back inside the classroom, Sheffield was packing up his gear, still smiling from the morning of music. Four years ago, he graduated from Adult Ed. Thursday, he said that he was glad to be back and sharing his musical skills with the group.

“When I play, I’m in a place where nothing else matters but the task at hand,” he said. “I just escape to a place where like, I’m a kid again, except I have this ability of reading the room.