Culture & Community | Downtown | Jazz | Music | Arts & Culture | Musicians | Toad's Place

Top: Alex Bugnon and Najee play at Lawrence's memorial service Monday night (David Livolsi is on bass in the background). Najee appeared with the band in the same configuration that it was when he was touring with Lawrence in the 1980s: himself on flute and sax, Bugnon on keys, and Poogie Bell on drums. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The first strains of “Amazing Grace” drifted heavenward from the Toad’s Place stage, and mourners fell to a hush in the audience. At the mic, Najee held decades of memory in place as he lifted his flute to his lips. Alex Bugnon joined in on piano, his fingers pressing down on the keys. Behind the musicians, photographs of Rohn Lawrence rotated in a slideshow: Lawrence playing Twister with his siblings, Lawrence shredding at a festival, Lawrence picking up his son Rahni and laughing that big bellied, gruff laugh that was his.

It felt strange that he was no longer there onstage, jamming with them.

Musicians, family, and friends all gathered to honor Lawrence’s life at Toad’s Place downtown Monday afternoon and evening, still reeling from his unexpected death on Dec. 30. From an out-the-door line and visitation to an hours-long elegiac jam session, friends showed up from every decade of his life, ready to pay their respects and send their stage brother off in song.

His family does not have a confirmed cause of death, but suspects that it was Covid-19. Howard K. Hill Funeral Services and Toad’s Place owner Brian Phelps worked together on the event, dubbed a “Last Call with Rohn Lawrence.”

It marked the first funeral at Toad’s, where Lawrence played a Monday night jazz jam upstairs at Lilly’s Pad for over a decade.

Rahni Alexander Lawrence and his mom, Lawrence's former wife Jacqueline (Jackie) Buster. "This is bittersweet for us, because you always want people to get their flowers while they're alive," Buster said. "Rohn was the consummate guitar player. We know that. Not only because of how he played and how he touched everybody in this room. Some say Rohn never got his flowers, not the ones that he deserved."

“I just want to say that for as proud as he was of me, I was twice as proud of him for everything that he's done for me while he was here,” said his son Rahni Lawrence, who drew tear-muffled applause when he greeted mourners with a patented Rohn “hey hey hey.” “He truly was my best friend, and the best entertainer I ever met. So it's only fitting that we have this here.”

For hours over Monday afternoon and evening, the sendoff lifted up the life of a musical genius. By a little before 2 p.m., a line for visitation already stretched halfway down the block, as attendees bounced from foot to foot in masks and heavy winter coats trying to stay warm. Inside, an open casket sat surrounded by a guitar, saxophone, and faded portraits of a young Lawrence that accompanied sprays of white lilies, chrysanthemums and gladioli.

Clementine Johnson.

Fifteen people deep, Queens resident Clevin Brailsford looked back on decades of working with Lawrence before becoming a school administrator. In the 1980s, Brailsford was a young manager working for the internationally acclaimed jazz musician Najee, and traveled the world with Lawrence. He remembered watching the band take the Blue Note Tokyo and feeling mesmerized. Even after he left that life behind him to work for the city’s school system, he never forgot the feeling of sharing a room with the musician.

“I loved him,” he said. “His solos were just memorable.”

Just a few steps in front of him, baker Clementine Johnson waited with a coat pulled tight around her black apron, ready to say a final goodbye after years of hearing Lawrence play. Years ago, the two met at a Monday night jam at Lilly’s Pad, where she fell in love with his style. She followed the shows out to the Chowder Pot in Branford, where she knew she could go for “a low-key, down-to-earth time.” As she built a business called Heavenly Icing, she often baked cakes and cupcakes to show her gratitude. Lawrence loved them, she said.

.jpg?width=300&name=RohnFuneralJan22%20-%201%20(2).jpg) As the front doors heaved open, friends and family poured inside the venue, some already crying softly as they lined up around the stage for a viewing. They filed across it one by one, some stopping to graze his hand and cross themselves. In an area set aside for a sort of mid-afternoon wake, no one seemed eager to leave quickly, as if their memories were more likely to stay intact inside Toad’s.

As the front doors heaved open, friends and family poured inside the venue, some already crying softly as they lined up around the stage for a viewing. They filed across it one by one, some stopping to graze his hand and cross themselves. In an area set aside for a sort of mid-afternoon wake, no one seemed eager to leave quickly, as if their memories were more likely to stay intact inside Toad’s.

Lawrence’s older sister Michelle Lawrence, who grew up calling her brother “baby Rohnnie,” walked around, greeting people in a floral mask, often shoulder-to-shoulder with her cousin, Judy Slaughter.

Now a lab technician in Portsmouth, Virginia, Michelle recalled watching her little brother toddle over to her godfather’s bongos as a small child, and begin to play them with a wisdom and precision well beyond his infant years. When he was two, he would stand in front of the television set with a Mickey Mouse wind up guitar, mimicking the motions of musicians he seemed too young to know. Before his 10th birthday, he had started to master the guitar, and also played keys, banjo, and mandolin.

Before she moved to Virginia in 1991, Michelle was often the doorman for Lawrence’s shows at the Foundry Café, the Audubon Street music venue where Koffee? now stands. She went to as many of his shows as she could, including one last November in Hampton, Virginia. The last time they saw each other was early last month, when she came up to New Haven for a relative’s funeral. They always remained close, she said: before his death, the two talked multiple times per week, sometimes as often as every other day.

“I’m just numb,” she said. “I don’t even know what to say.”

A photograph of a young Rohn Lawrence (at far left) sat on each table before the evening service.

Floating through the concert venue, Andrea Rodnick-Case dabbed her eyes, only to find that they were wet again moments later. Raised in West Haven, she met Lawrence in middle school, and recognized his talent even then. As his career blossomed, she followed him around, from Lilly’s Pad to the Milford Green to the Tipping Chair. She described herself as “still in shock” after learning about Lawrence’s death just before the new year.

“He’s the most talented guitar player ever,” she said. “He was a good soul. A good soul. Honest to the core.”

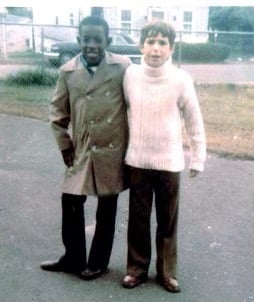

Nearby, Robert Paturzo flipped mentally through decades of memory, from a childhood spent with Lawrence and his family to recent years in which the two remained close, and would often meet up for drinks and dinner at Christopher Martin’s. Paturzo's dad died when he was young, and Lawrence’s father Harold became a second dad. They remained best friends for the better part of six decades (they are pictured as kids below, courtesy of Paturzo).

“We grew up in each others’ houses,” he said. "His parents were like parents to me.”

By middle school, it was clear to Lawrence’s friends that he was already on his way to guitar stardom. Paturzo said that parents would call the school each year, and ask that Lawrence be barred from the school’s talent show. When he played, in concert-like performances that stupefied the student body and the staff alike, it wasn’t even a contest. Paturzo remembered watching him play “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” leaving everyone on the edge of their seats.

As the two grew into adulthood, Lawrence became a confidant and close friend, whose talent lived alongside a generosity of spirit. When the two were 15 or 16, Paturzo watched him play a mixer at Notre Dame High School. When he asked Lawrence why he was playing the drums, his friend gave him a matter-of-fact reply: "The band needs a drummer.” He was a musical shape-shifter in that way, slipping onto the stage wherever he was needed without the slightest objection. He was also a faithful friend, and found the time to care for Paturzo when he needed help and reached out.

"He could play anything," Paturzo said. "One of the things Rohnnie said to me, and not only to me, he said it to a lot of people, is there's only two kinds of music. Good music and bad music. These were the words that he'd say: ‘If you're playing a polka and you're playing it well, it doesn't matter.’”

The last time they spoke was the Sunday before Lawrence passed. The memories he has are "where I'm getting my strength from now," he said.

Charlie Grady and Herman Badger.

Project Longevity’s Charlie Grady also met Lawrence through his parents in elementary school. When he was a kid, Lawrence's father Harold had given Grady's dad a job, his first on the East Coast after moving from North Carolina. By the time they were in their teens, the two were band mates. Their group, Good News, “played all over the place,” including the old, beloved Richter’s Bar when it still hosted live music on Chapel Street. Monday, Grady volleyed memories back and forth with Herman Badger, a fellow classmate from Carrigan Elementary School.

“It didn't matter where we played, because he was just that much of a natural, raw talent,” Grady said. “Everybody recognized it from a young age.”

Many of the afternoon’s attendees were fellow musicians and Monday night jazz regulars, from longtime bandmates to lifelong students who had soaked up every drop of Lawrence’s on-the-job knowledge as they could. Jay Rowe and Trever Somerville, who played Monday nights with Lawrence for two decades, remembered how tightly they worked as a unit.

As the show matured from the old Rudy’s to Jackie’s Blues Cafe to Humphrey’s East and then Lilly’s Pad with a rotating cast of musicians, the three were “automatically family,” Somerville said.

Trever Somerville and Jay Rowe. Somerville joked that he is the "baby of the bunch:" he was born the same year that Rowe and Lawrence met at ECA.

“It didn't matter how many times we played,” he said. “Each time we played, whether it was the same song, that magic came through in a different way.”

Rowe, who grew up in Milford and met Lawrence at the Educational Center for the Arts (ECA) in 1979, remembered how pronounced the musician’s style was by the time he was a teenager. Slipping in between past and present tense, he described Lawrence as “pretty much like he is now, just in a 19-year-old's body.”

“Rohn had a lot of maturity for a 19-year-old kid,” Rowe said. “His basic style was kind of formed back then, you know. And he would refine it over the next 40 years. He was one of the best musicians I ever played with. It was an opportunity for me to learn and take advantage of his knowledge … We ended up having a really good interchange. Rohn had so much feel.”

The last time the two played together was Dec. 23, a week before Lawrence’s death. Rowe said they spoke frequently, including the day before Lawrence passed. They chatted about an upcoming recording project. "We were looking to the future, for sure," he said. "My final memory is hanging up the phone laughing."

Dave Livolsi and Timmy Maia. "Rohn could play at Madison Square Garden on Sunday night and be back at Humphrey's on Monday," Maia said.

Amid Toads’ low-hanging posters and neon green lights, it seemed impossible to take two steps in any direction without a fresh flood of memories, musicians often crying in each other’s arms. Laura McClam-Williams, who attended ECA for voice at the same time Lawrence was a student, recalled the “unstoppable” guitarist who always made time for her to jump on the mic if she rolled up at a gig. Around her, Monday night regulars who attended hundreds of Lilly’s Pad performances, pointed to how quickly Lawrence could transport them from a downtown New Haven venue to another stratosphere entirely.

Musicians Dave Livolsi and Timmy Maia remembered their early days in F.U. Jazzboy, which played Humphrey’s East every Monday for years. Ed Natera, who owned Sidebar on Orange Street for years, spoke of how Lawrence would reliably pack the house—with a line down the block to boot—dazzle the audience, and still make time to ask after Natera’s young son before the night was over.

“It's a great loss to New Haven,” Natera said. “He really is the fabric, the foundation, the backbone, of what essentially was ... what really tied people together. if you look around, there's not a face in here I don't recognize. Rohn was a big part in building social community."

Top: Foundry Café regular John Scott and Ed Natera. Bottom: Several of Lawrence's Monday night regulars. Eric Triffin, in the color block sweater, estimated that he's been to 500 of Lawrence's Lilly Pad performances. Star, crouching in the star mask, said that she's watched Lawrence play for 15-20 years. Stephen Messina, wearing the hoodie in the center of the group, loved to dance as Lawrence played. "Being at a Rohn Lawrence show, it was like floating through the milky way," he said. "You never wanted it to end."

Phillip Bynum, who went on to found the Cool Breeze Music Series in which Lawrence regularly played, recalled playing both music and basketball with him as a kid in West Haven, where “our talent shows was little concerts” because Lawrence was so sharp on the guitar. With a masked smile, Bynum remembered how Lawrence only told a handful of friends his secret childhood aspiration: to be a Harlem Globetrotter. Instead, he left his mark on thousands of musicians.

“Not only was he a friend, a musician, a legend, but he was our brother,” he said.

It was a musical sendoff Monday, with video tributes and performances that stretched into the night, that perhaps best encapsulated Lawrence’s outsized footprint. As cousins lifted the casket and accompanied Rahni to a hearse waiting outside, musicians gathered by the back door of the venue, watching as their friend made his final exit from the stage. Pallbearers slowed at a loading ramp that someone had moved to cover the stairs.

“C’mon Rohn, we going,” someone shouted.

“He doesn’t want to go,” came another reply from somewhere in the crowd. A wave of low laughter, sometimes wavering and tearful at the edges, followed.

Andrew Sherman.

As they headed to the street, musicians scrambled to set up the stage in record time. Strains from Lawrence’s 1998 See Ya Around drifted through the air. Rowe jumped in as emcee, carrying every performance of the night. After tributes from longtime collaborators Marion Meadows and Morris Pleasure, Rahsaan Langley took the stage.

“C’mon now, c’mon,” he said after an anemic response from the audience. “You know how Rohn was. Rohn used to always tell us, ‘Don’t cry for me.’ He used to always tell us that. And no matter times I hear that play in my head, I always end up crying.”

He launched into Christopher Cross’ “Sailing,” one of the songs he loved to play with Lawrence. Looking to the musician’s beaming face on a screen behind him, he saluted Lawrence, crooning smoothly. Then his voice wavered. During a drum solo from Smokey Ivory, he covered his face with a scarf and began to weep. In the front row, Rahni stood in support as he finished the song.

Andrew Sherman, who performed in and produced Lawrence’s 1994 album See Ya Around, met the musician when they both played for Najee. For three weeks, the band rehearsed together at Malcolm's, which no longer survives. A year later, Sherman and Lawrence became roommates in Boston, starting a weekly funk night at the long-running venue Wally’s Jazz Cafe. He and a fellow producer became writers with Lawrence, publishing under the moniker Bread and Butter.

“I cannot believe he is not here right now, because he should be playing this,” he said before playing the melody for “Out In The Park Til’ Dark.” “I miss you, Rohn, already. I miss you already.”

In performance after performance, musicians paid homage not only to their friend, but to a New Haven of which he was a building block—a New Haven that risks erasure as musicians grow older, and the spots in which they trained and taught disappear from public memory. When Sherman asked who in the crowd remembered Malcolm’s, only a few cheers went up from the audience. Coffee shops and grocery stores line Whitney Avenue and Audubon Street where jazz music once bounced from venue to venue. 259 Orange St. has lived multiple lives, none of them musical, since the closure of Sidebar.

But when an era of musicians from the Foundry Café days gathered to play onstage, when Najee’s original band reassembled for the night, when Maia got mourners on their feet, all of that melted away. Joe Melotti dedicated Donny Hathaway’s “A Song for You” to Lawrence, replacing the first refrain with “I’m singing this song for Rohnnie, can’t you see?” It felt fitting.

“We know he’s here with us,” Najee said.

Watch the full musical tribute to Rohn Lawrence in the video above.