Food & Drink | Music | Storytelling | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

| Screenshots from Faccebook and YouTube. |

One saw it from the backseat of a space-blue, 1992 Mercury Tracer Wagon. Another found it in a ballad about American heavy-weight boxer Joe Frazier. A third unearthed it in the midst of linguistic confusion. All had a “fighting story” to tell.

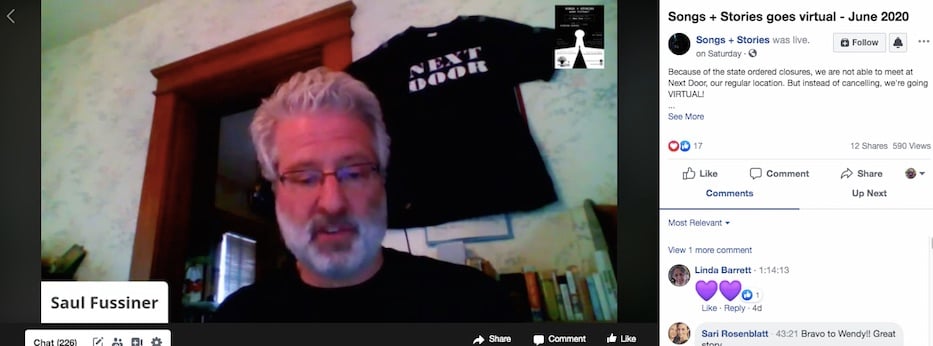

On Saturday evening, Songs and Stories held its virtual debut over YouTube livestream and Facebook Live in conjunction with Baobab Tree Studios. Writer and storyteller Saul Fussiner, who chairs the Creative Writing department at the Educational Center for the Arts, founded the monthly singing and storytelling event in August of 2019.

Next Door New Haven hosted the series through March of this year, when the restaurant closed its doors due to COVID-19. Before the pandemic, close to 20 staff members worked at the bustling neighborhood spot, which sits just across from Jocelyn Square. When it reopens July 10, it plans to come back three days a week with fewer than 10 employees. Fussiner hosted Saturday's event as a fundraiser for staff who have been out of work during this time.

Viewers could donate as Fussiner moderated the program. Co-Owner Robin Bodak, who runs the kitchen, praised Fussiner for his efforts.

“It's just an incredible time,” she said Wednesday, reached by phone. “It really is. My fingers are just crossed for everyone right now. Not just for me. Those stupid sayings about it takes a village, it's true. It takes a lot just to make things grow and be viable.”

In the series' format, three storytellers and three singer-songwriters take on the same theme, often with wildly different results. The installment’s theme, mothballed from March, was “fighting stories." Despite the potential for screen fatigue, several viewers and performers noted that they felt connected across the distance. It made the event, in turn, feel distinctly human.

“I don’t know how you did it after three months of zooming and other things, but tonight, I actually felt like I was with you all,” said storyteller Wendy Marans.

The livestream’s chat buzzed in accord.

Left-Hook: Buzz Gordo

Most know Gary Mezzi by his stage name, “Buzz Gordo.” “Buzz” has an edge—you can feel it in the way the double-z’s sizzle just behind your teeth. The z’s in “Mezzi” wilt into sorry s’.

“The first performer tonight makes me think of the really cool British singer-songwriters in the late 1970s,” Fussiner said. “His lyrics are smart and funny, and he’s got a little bit of that snarl in his voice.”

Buzz Gordo is the lead vocalist of popular New Haven rock band Bronson Rock. The group will release its second album in September.

“The man has a willingness to experiment with various forms around the edges of rock and roll, country, rockabilly, power pop, and early punk,” Fussiner announced. “Now, I present to you, Buzz Gordo!”

“Heh, thank you, thank you, wow!” Mezzi seemed to shrink bank, embarrassed at the praise. “What a nice introduction! This is my first time doing an actual live-streaming show! I hope my Wi-Fi holds up.”

He readjusted his harmonica neck holder and fiddled with the strings of his guitar. “I couldn’t do songs and stories about fighting without doing ‘Smokin’ Joe.’ I wrote this song about former heavyweight champion Joe Frazier.”

With the strum of a guitar, Mezzi became Buzz Gordo. Gordo danced from side to side, fingers changing chords and bellowing lyrics with his mouth open wide.

Smokin’ Joe could take a punch,/But he gave back a bunch,

Working hard was how he hung on to the crown!

He threw his head back. The voice’s scratchy timbre belonged to the country, warm and inviting. He closed his eyes.

As a boy in South Carolina,/He was fired,/His daddy still,

When he wasn’t making whiskey,/He was plowing on the hill!

Buzz shook his head and gritted his teeth. His sorrow radiated through the screen.

Then he came up North to Philly,/Found work in a slaughterhouse,

When his left-hook got perfected,/By him slinging it at the cows!

Frazier ostensibly perfected his famous left-hook punching sides of beef in the slaughterhouse’s refrigerated room. Gordo was a fan of the strike. He sent Frazier “Smokin’ Joe” right before the former champion’s passing.

“A personal secretary said, ‘Joe Frazier’s on the phone for you if you’d like to talk to him,” he reminisced in front of his camera. “I said, ‘Hey, champ, did you like the song?’”

“In his Clint-Eastwood-tough-guy voice he said, ‘Yeah, it was alright.’”

“I asked how the left hook was, ’cause that was his signature punch.” Buzz paused for a moment.

“He simply answered, ‘Can’t kill it.’”

Love is Road-Rage in Red: Jezrie Marcano-Courtney

For Jezrie Marcano-Courtney, the fighting came closer to home. She launched into a story of watching her parents navigate a bout of road rage from the backseat of the family car.

“There are things that I’ve come to discover about my parents, especially my mother,” she began. Out of all those things I’ve come to discover, two are stuck at the forefront of my mind—First, she smokes a lot of cigarettes when she fights with my dad, and two, you do not give my mother ‘the finger.’”

She took a deep breath, squared her shoulders, and stared at the audience beyond her small room.

“This spring of 1993 buds and blooms to the soundtrack of my parents arguing,” she started. “They are in the process of buying our forever home. Money, how much they can spend, and where in the city they can spend it to find our house erupts into bickering and bitter dispute. On a Saturday mid-morning drive, they’re at it again.”

Marcano-Courtney was ten at the time. She and her 9-year-old sister sat in the backseat of the family’s space-blue 1992 Mercury Tracer. Her father sat at the driver’s seat, scowling. Her mother was on the passenger side, itching for a cigarette. Marcano-Courtney peered between them, looking through the windshield to watch the road.

Suddenly, she saw something strange through the windshield—a red vehicle. The car itself was unremarkable, but its course left her wary. It’d changed lanes, so it was in front of the Mercury Tracer and had begun to slow down. The family car maintained its usual break-neck speed.

As the distance between the cars shortened, Marcano-Courtney weighed her options. She could either watch the collision about to take place or interrupt her parents’ argument and “incur their wrath.” She chose the latter.

“Guys?”

“What?!” Her parents whipped around, screaming at her in unison.

“I think they’re playing chicken with us.” She pointed her finger forward.

Her father swerved right before they hit the car’s bumper. The red vehicle switched to the leftmost lane. Marcano-Courtney and her family spied the two, college-age girls laughing hysterically in its front seats.

“Daddy, they’re laughing at us!” Marcano-Courtney piped up.

What ensued next Marcano-Courtney would never forget. Her father slammed his foot on the accelerator and crossed several lanes to jam his Mercury Tracer in front of the red car. He played the girls’ own game, forcing the red car to swerve to the side of the road and park. Marcano-Courtney watched as her father stormed out of his vehicle along with his wife (who now lit the cigarette she’d been longing for the whole ride). Marcano-Courtney and her little sister peer through the Mercury Tracer’s windows to watch the show.

One of the girls was in tears, refusing to open the red car’s doors nor windows. The other girl got defensive, giving Marcano-Courtney’s parents the finger. Her mother threw down her cigarette and jumped on the car’s hood, sitting on her haunches to thump the windshield. Her father punched at the windows. Marcano-Courtney and her sister had never heard so many cuss words in their lives.

When the college-age girls were holding each other, reduced to tears, Marcano-Courtney’s parents were satisfied. Her father picked up his wife (who was still thumping on the windshield) and carried her to their space-blue, 1992 Mercury Tracer. The two sat down. Her father lightly started the ignition and silently pulled back onto the road.

Her parents gazed lovingly at each other. Their daughters were confused.

“I don’t know who you people are,” Marcano-Courtney said flatly. “Bring back my parents.”

/təˈmādō/, or /təˈmätō/, that is the Question: Wendy Dalton Marans

“I am bicultural and bilinguistic. I speak British English and American English, and sometimes, the differences between the two are quite trivial.”

Wendy Marans folded her hands and gave a wistful sigh. “When I’m in England, I ask for chips, and here, I order French fries. In England, I walk on the pavement, but here, I walk on the sidewalk. In America, we say ‘toe-may-does’ and in England’ toe-mah-toes.’ However, sometimes the differences between these two cultures and languages are not so benign.”

Marans was the picture of poise and sophistication Saturday. Her video framed herself and a bookshelf crammed with tomes. Her glasses were perched perfectly on her nose. She’s served as the president of Music Haven and as a Communication Disorders Specialist for many years.

But, she soon explained, all that grace and intellect couldn’t save her from a series of social misunderstandings. The first had occurred in the 1980s, living with her American boyfriend in a London flat. They’d been arguing for hours, and both were fed up.

After a minute of howling at each other, Marans turned around and screamed, “Oh, shut up!” The room fell silent. Marans stared at her boyfriend; he looked wounded, eyes beginning to show genuine hurt. She’d crossed a line.

“What’s the matter?” Maran tried.

“You don’t say ‘shut up’ to people,” Chris explained. “It’s rude!”

Though confused, Marans took his words to heart and stuck “shut up” under lock and key.

A few weeks later, the couple decided to visit a free gallery within the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London. Its featured exhibition was by English director Derek Jarman. At the time, Jarman had been into the English punk scene and had directed a radical version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. After looking around for a bit, the couple spied a massive hardwood bed. Marans and Chris thought it resembled an elongated settee. Keen to capture the unique sculpture, Chris pulled out his notebook and began to sketch.

Suddenly, a tall, skinny man with a nose ring and a safety pin in one ear slouched over. He stuck out his hip and pointed a bony finger at Chris.

“Oi, I don’t want you sketchin’ my bed! That’s my bed, and I don’t want you sketchin’ it!”

Chris quickly apologized. The man repeated his statement and slunk back to his corner on the other side of the room. After a bit, Marans realized the man had been Jarman. Mortified, she scurried to another piece of artwork in the room.

Marans hadn’t noticed Chris wasn’t following her—what she saw next made her heart sink. Chris had walked over to Jarman, looking none too pleased. Marans heard the following conversation from afar:

“You know, that’s a beautiful design, but you aren’t exactly subtle,” Chris snarked.

“I ain’t subtle.” Jarman glowered.

“No, you’re an asshole,” Chris retorted without missing a beat.

Jarman took a step back and grabbed his chest. “You don’t say ‘asshole!’” he screeched.

“You are, you’re an asshole!” Chris jabbed his fingers toward Jarman’s face.

“You wanna fight?!” Jarman held up his fist, and Marans watched horrified as Chris mirrored him.

Maran ran out of the building, more embarrassed than she’d ever been in her life.

Marans seemed to smirk at the livestream’s audience. In her perfectly poised tone, she uttered:

“So, what I took away from this is that in America, you can say with impunity, ‘you asshole,’ as long as you don’t say, ‘shut up you asshole!’ They did not teach me that in citizenship class!”

Careful, Porcelain Doll: Lara Herscovitch

Lara Herscovitch’s fighting stories stoked viewers’ embers on Saturday evening. Her most poignant song, titled “Careful Porcelain Doll,” was about fighting for oneself. The song comes from her latest album, Highway Philosophers.

Mmm-hmm/I was gonna be a New York Yankee,

Number Nine,/Protect the left field from the third-base line

Herscovitch’s bright voice rang clear through the night air. She strummed a steady beat with her guitar, fingers finding a minor chord that sat deep, tugging at your navel. She brushed a blonde curl from her face and began the song’s chorus.

Paint by numbers in reverse,/In reverse,

In a league above it all,/Had no time to be a careful, porcelain doll.

The livestream’s chat remained untouched. All eyes were on Herscovitch. Her eyes were clouded. Her tone was smooth, almost bewitching.

Red wine, white dinner jacket before Labor Day,

Silver candlesticks all in their rightful place,

In a long, white dress,/Waltzing in a rented hall,

Smiling like a careful, porcelain doll.

Her voice remained clear, steady, but her eyes looked pained. The song was clawing at something deep inside. What that was, viewers could only guess.

Ceramic and Pearl,/Pirouetting, ballet, and tiny tea-cup whirl,

Or rosewood, six-string steel,/Searching sawdust to figure out what I feel

In reverse,/In reverse,

Life is asking,/Every time to rehearse!

The song’s bridge had irregularities in its rhythm, almost as if the speaker was becoming unhinged.

I sprinted into the nearest brick wall

To break all remaining careful, porcelain doll.

Herscovitch’s gaze became resolute, steely. She gave a last strum and took a large breath.

‘Cause music above it all,

I have no time to be a careful, porcelain doll.

Letters from the Battlefield: Arnie Pritchard

Arnold “Arnie” Pritchard’s story was a small piece of a vast anthology, a sliver of a period long forgotten. He based the tale on his father’s letters home to his parents from the war front of World War II.

At the start of the section, Anton Prichard was a “forward observation officer of an artillery battery.” Pritchard oversaw a small squad of soldiers on the battlefront. The team usually ran a mile forward of heavy artillery and acted as scouts; members used radios or field telephones to provide intel about enemy positions and conditions of the battlefield ahead.

The group had just crossed over from England into France to join the Normandy campaign in 1944. It was a liberation of northern France from Nazi forces, lasting June through August of that year.

Dear Mom and Pop,

There are times in a person’s life, it seems, when a little mental wrestling has to be done, and that wrestling can’t be shared with people 3000 miles away—try and understand that. But let me set you straight lest you become alarmed at my musings. My health is excellent—eating and sleeping well, and I can still see a joke at every turn of the road. I’m tired, and I gotta get some sleep. The end is in sight, dear people. Until then, for complete details, see our local newspaper— they know much more about this war than we who are fighting it.

Cheers,

Anton

PS: The only package I’ve gotten is the one with the two boxes of chocolate. Can you start another one with candy gum lifesavers?

Despite his optimism, Pritchard’s inner musings became darker as the realities of war crashed around him. By August 16, 1944, the soldiers were liberating ten French towns a day. Nazi attacks were erratic, laced with a ferocity and viciousness Pritchard had never seen before. He described the physical and emotional toll of interacting with German soldiers, which dominated every waking hour—even when they weren’t directly attacking.

There were no pleas for sweets or jokes anymore. Pritchard was hardened. The 3,000-mile gap between him and his parents separated them less than the war did—he was not their Anton anymore.

Still, he sought light in his deluge of darkness. The war wasn’t just gutters and gunfire—it was the smiling faces of liberated French citizens. It was the tears of relief that streamed down their faces and the tattered American flags they waved in celebration as soldiers marched on. Those smiling faces laughed in the face of human cruelty.

Forty years later, Anton sat with his son on a hot summer day. He told the younger Pritchard about the war, how he’d gotten shrapnel from German mortar fire caught in his leg. He told him about the blood that had run red down his thigh. A fellow soldier had discovered him unconscious and had carried him to the medical tent; Anton almost died.

“That is not my father's whole story, but it's what we have time for tonight,” Pritchard said. “If anybody out there is interested in dipping their toe in storytelling, the Institute Library story sharing group is a very low-pressure, enjoyable way to start. We welcome people of all levels of experience—even no experience. If anybody wants to hear all of my father's story, above and beyond the section you heard tonight, get in touch with me.”

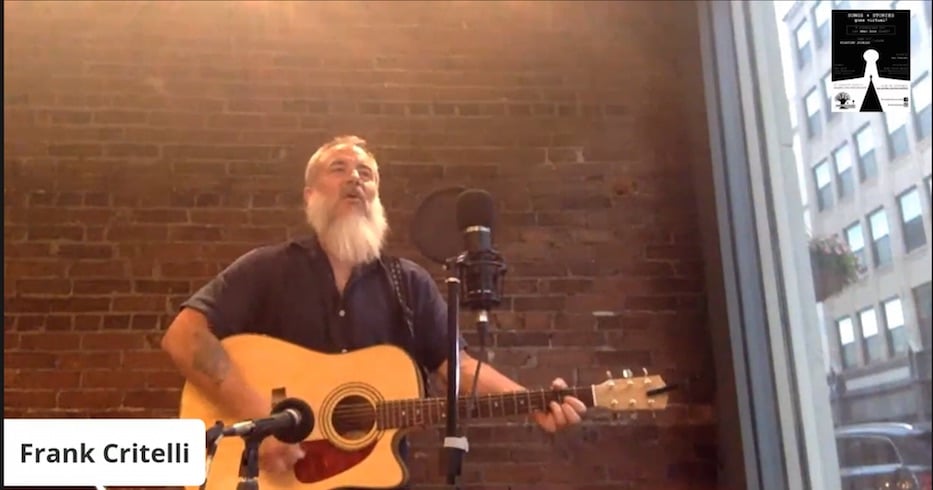

Friction in Friendships: Frank Critelli

Frank Critelli plays where the music takes him, he explained. He is the co-host of The Local Bands Show on 99.1fm WPLR-New Haven and The Beer Show. He brought his love of beer and song to the inaugural Songs and Stories, performing at its first event in August of 2019. He performed his song “Reflections on a Friendship Heading South.”

That’s the way it goes/It’s a game

That he plays,/But Nobody Knows

It’s the same/Mistakes/Again.

The twang of Critelli’s voice matched the steady pluck of his guitar. While the folk ballad was in a major key, the composition was deceptive—the cheery tune veiled a deep hurt. Critelli’s lips twisting into a snarl as he sang.

“The theme today was fighting,” he said. “But I’m a lover, not a fighter.”