Legislative Agenda | Arts & Culture | State Legislature | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

Toni Walker was three years old the first time she faced hair discrimination. Decades later, the New Haven state representative is still watching it happen to her colleagues—and experiencing it herself. She’s ready for that pattern to end.

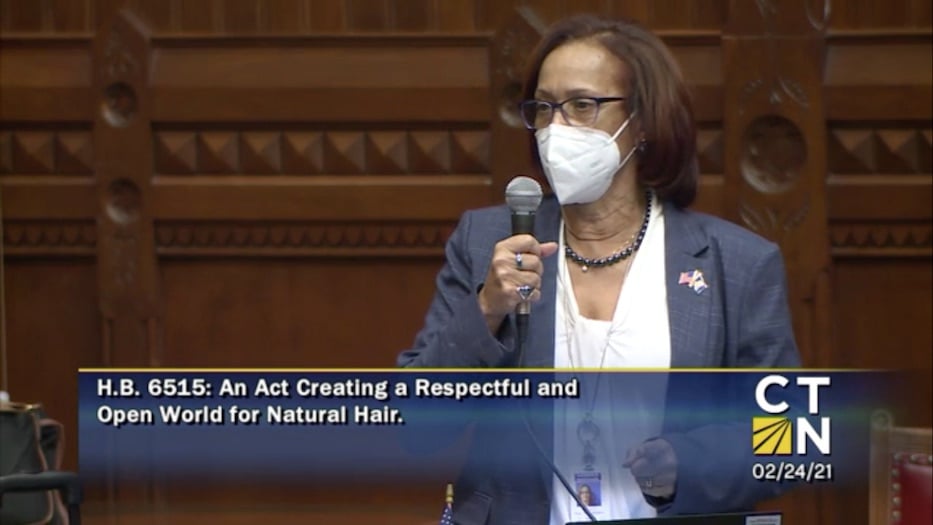

Walker told that story to the Connecticut House of Representatives Wednesday afternoon, as An Act Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair was approved by the House, and now moves on to the State Senate. More commonly known as the CROWN Act, the bill would prohibit discrimination of natural and protected hairstyles in the workplace, as well as in housing, public accommodations, education, and credit transactions.

The measure, which passed in a 139 to 9 vote, would add natural hairstyles to protected classes included in statewide anti-discrimination laws, as overseen by the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities. Those include locs, weaves, box braids, bantu knots, twists, afros, afro puffs, wigs, and head wraps. Proposed by New Haven State Rep. Robyn Porter and Danbury State Sen. Julie Kushner, it recognizes that hair-based discrimination is often used as a proxy for anti-Blackness in schools and in the workplace.

“It brings me great ancestral joy and pride to lead the passage of this piece of legislation in the House,” Porter said Wednesday, dressed in a vivid African wax-print pattern that danced with yellows and blues. “My people have since long beared the burden of conforming and assimilating in the hopes of fitting in and being accepted. The CROWN Act is a public declaration that we will no long accept being discriminated against for the way we choose to adorn our crowns.”

If Connecticut passes the bill into law, it will join California, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, Washington and Colorado in doing so. CROWN Act legislation has also been proposed in 19 other states. Read more about that here.

Before the vote, legislators spoke passionately on the bill, which has become personal for many of them. Walker, who represents New Haven, took her colleagues back to her childhood in North Carolina, on a day when she and her mother had gone shopping at the department store chain W.T. Grant Co. While her mother shopped, Walker realized she had to go to the bathroom.

Before the vote, legislators spoke passionately on the bill, which has become personal for many of them. Walker, who represents New Haven, took her colleagues back to her childhood in North Carolina, on a day when she and her mother had gone shopping at the department store chain W.T. Grant Co. While her mother shopped, Walker realized she had to go to the bathroom.

She spotted a nearby door, into which white women were walking freely. So she followed them. Before she could enter, a store clerk—“I shouldn’t even use the word gentleman,” Walker said—pulled her out of the room by her hair. He told her mother to “take your nappy-headed kid outta here,” she recalled.

Walker knew, in that moment, that she was being punished because she was a young Black girl. She recalled the number of times she’s watched employers, landlords, and teachers judge Black people for the color of their skin, the texture of their hair, and other physical characteristics. Thanking Porter as her “little sister,” she urged her colleagues to support the bill.

“This is real,” she said. “It is so real in our lives that it is painful. I want you to understand it. I don’t expect you to totally walk in my shoes. But we’re not lying about this. We’re not exaggerating about this. You see the lives of our families and friends losing it because of the fact that we’re being identified, we’re being killed, we’re being isolated, we’re being ignored. Education, housing, job opportunities—we’re at the bottom. And do you think we want to be at the bottom? Do you think that this is where we are comfortable?”

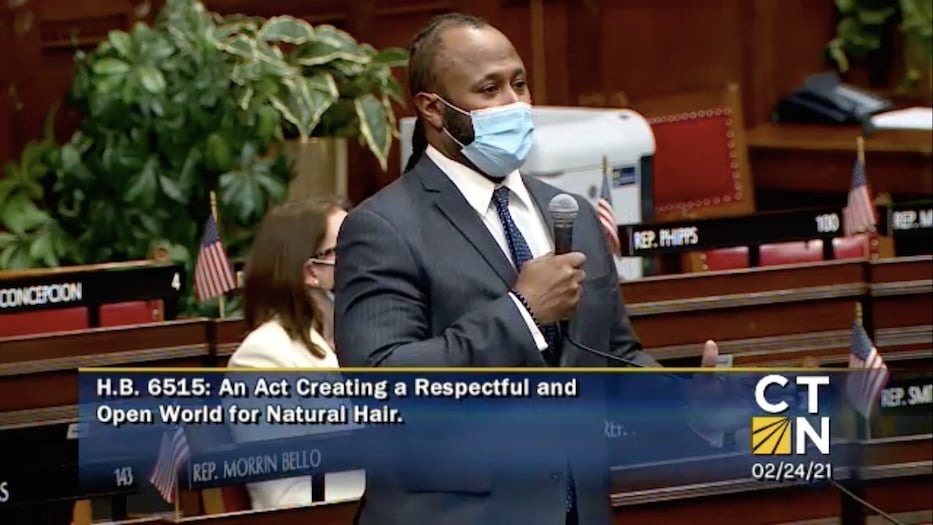

When it was his turn to speak, Hartford State Rep. Brandon McGee summoned his wife and two young daughters, Silver and Bailey. Sometimes, he said, his wife wears her hair natural. Sometimes she straightens it. It should always be her decision—and have no bearing on how she’s perceived at work. He called it doubly important to pass the legislation for young people, who are often told to cut or chemically alter their hair before playing sports, participating in their classrooms, or going for job interviews. He’s been one of those kids, he said—a teacher once advised him to cut off his locs.

“For me, the goal is not just to eliminate the gap between white people and people of color, but to increase the success for all people,” he said. “All people.”

“Women have always, they’ve always, had to deal with societal pressures to look a certain way,” he later added. “But if you’re Black in America, the stakes of that message are higher. Conformity is often a means of survival for many of our Black and Brown women.”

Stamford State Rep. Patricia Billie Miller said that she had started the day feeling “saddened, because we have to put into law that a person should not be discriminated against because of the texture or style of their hair.” She remembered growing up in the 1970s, when it was stylish to rock an afro. When she graduated from college, Miller realized that a bevy of white employers expected her to straighten her hair or risk losing out on job opportunities.

“Unfortunately we have to put these things into law,” she said. “Because if it wasn’t for law, my people would still be enslaved. If it wasn’t for law, we wouldn’t be able to vote. If it wasn’t for law, I wouldn’t have been able to go college. Unfortunately, society does not do what it is supposed to do. ”

She watched hair discrimination shape her own life, and the lives of the women and children around her. When her daughter was just four, she started to ask her mom to straighten her tight curls. Miller explained to those in the chamber that the process of straightening—whether by hot comb or by chemical treatment—fundamentally changes the character of one’s hair. She motioned to her dress, brightly patterned in yellow, pink, white and purple, as she spoke.

“I wear this outfit today because it reminds me of my culture,” she said. “It makes me proud of my culture. When I went to Africa for the first time, I felt connected to my African history. And I realized at that point that African-Americans have been so busy trying to assimilate that we’ve forgotten who we are. And I’ve decided that I’m not going to do that anymore.”

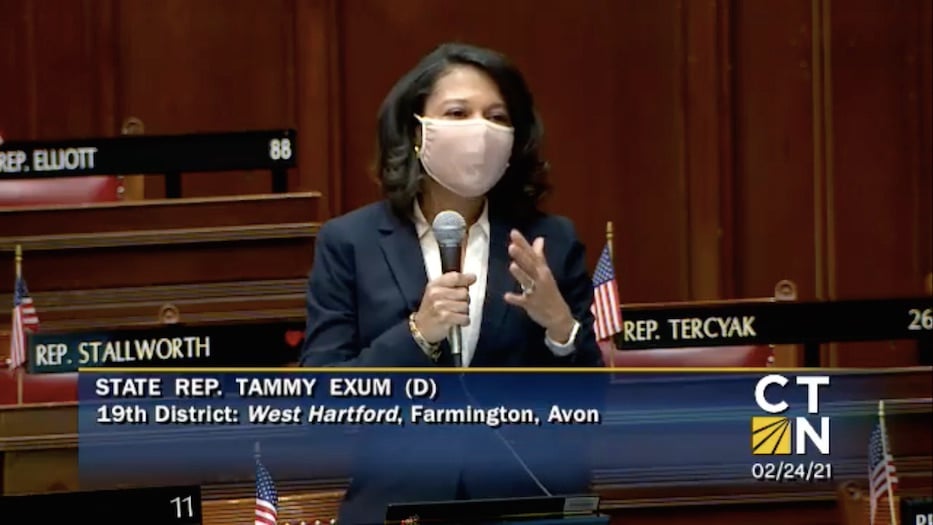

State Rep Tammy Exum also spoke in favor of the bill. “Unfortunately, when you have hair that isn’t straight, and when you have skin that is Black or Brown, it isn’t simply hair," she said. "It’s judgement. It is judged. It can be a key factor in employment, housing, union membership, education and so on.”

The bill received pushback from several of Connecticut’s Republican legislators, almost all of whom removed their masks to speak. Before voting against the bill, Greenwich and Stamford State Rep. Kimberly Fiorello argued that it was up to people, and not the state legislature, to end the racism that results in hair-based discrimination. Fiorello was born in Seoul, South Korea and grew up in the U.S. While “I never ran for office to represent Asian people,” she said that some colleagues see her first for her outward appearance.

Her remarks come at a time when, in the midst of the twin pandemics of Covid-19 and white supremacy, there has also been a sharp increase in anti-Asian hate crime across the country. She said that her son, who is half-Asian and half-white, faces race-based discrimination while playing sports. Multiple times, he has come home to tell her about racial epithets his opponents have hurled at him, “and it hurts me.”

And yet, she argued—the answer is not to put anti-discriminatory safeguards in place. Instead, she maintained that legislators need to trust people to take “the time to get to know each other, to talk to each other, to understand each other. ”

“We can pass laws and laws and legislation to address each and every instance of racism. Today, it is hair texture. But it will result in a lot of laws that regulate our behavior,” she said. “We pass a lot of laws … our fight to end racism will not be won by passing laws and more laws.”

State Rep. Bobby Gibson, who has taught in the Bloomfield public schools for years, noted that he saw students use their hair as a means of expression at a time when they were figuring out their own identities in the world. He recalled students who have been told that barred from proms, athletic events, and job interviews because of their hair. "This is a good bill and it needs to pass," he said.

Republican State Rep. Doug Dubitsky, who represents Canterbury, Chaplin, Franklin, Hampton, Lebanon, Lisbon, Norwich, Scotland and Sprague, said that he objects to the language of the bill. After questioning the bill’s use of the term "ethnic traits historically associated with race," he suggested that the legislation could have “unintended consequences.” He declined to list what any of those might be.

Others signalled their bipartisan support. East Lyme and Salem State Rep. Holly Cheeseman, a Republican, said she planned to champion the legislation, but slammed the Lamont administration for not doing more to support schools, Black-owned businesses, and non-white residents during this time.

Walker, who was fighting tears by the end of her testimony, urged her Republican colleagues to bring that same compassion for Black-owned businesses and underfunded schools to discussions around the budget and legislative agenda this year.

"I beg you all to understand that this is a symbol to say 'no more,'" she said. "I want to walk with you, shoulder to shoulder, because you are an amazing person. And I want you to be my friend."

An emotional Porter closed the debate with a final call to her colleagues to support the bill. She said that Wednesday’s debate reminded her of a similar one during last year’s special session, when police accountability was on the table. For a second time, she watched fellow legislators of color come into the space and “reopen our wounds,” pushed to share and relive traumatic experiences as a measure of legislative proof.

“At the end of the day, we can’t talk about liberty and justice for all until there’s equity,” she said. “Until there’s actually liberty and justice for all. And liberty for me and people that look like me is being able to show up in spaces, whether they’re workplaces, schools, classrooms, football fields, a wrestling ring, a skating rink—just public accommodations. We should be able to leave home knowing that how we show up and what we look like and how we wear our hair is not going to make people uncomfortable. That we are enough.”

Find out more about national CROWN Act legislation here. Read about the first hearing on the act here.