Culture & Community | Politics | Arts & Culture | State Legislature

Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

State Rep. Robyn Porter remembers how her colleagues questioned her natural hair when she got to the Connecticut State Legislature in 2014. Some talked around it, as if they were trying to mask their displeasure. Others warned her that fellow legislators, members of the press, and even her own constituents might not recognize her if she changed styles.

She doesn’t want that to happen to another Black woman—or any person of color—ever again.

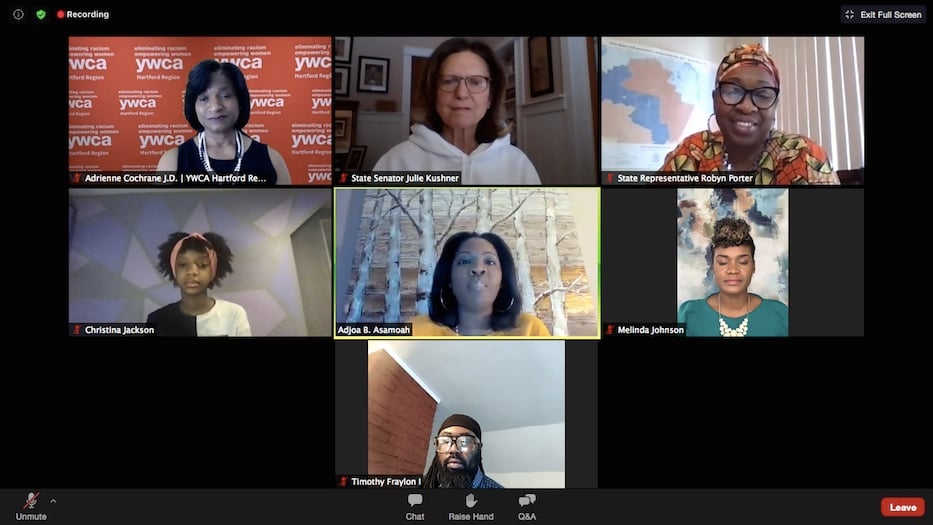

Tuesday, Porter told that story during testimony for House Bill 6376, An Act Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair, in a marathon hearing of the Labor and Public Employees Committee. More commonly known as the CROWN Act, the bill would prohibit discrimination of natural and protected hair in the workplace, as well as in housing, public accommodations, education, and credit transactions.

It would add natural hairstyles to protected classes included in statewide anti-discrimination laws, as overseen by the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities. Tuesday, Porter noted that natural hair includes but is not limited to locs, weaves, box braids, bantu knots, twists, afros, afro puffs, wigs, and head wraps.

It is co-sponsored by Porter, who represents New Haven and Hamden, and State Sen. Julie Kushner, who represents Bethel, Danbury, New Fairfield, and Sherman. The two first proposed the bill during the 2020 legislative session, which was stymied by Covid-19. While they tried to resurrect it as part of the State Senate's Juneteenth Agenda, the special session proved too short.

Throughout the hearing, Porter and others pointed to a 2019 study by Dove that found that Black women were 30 percent more likely to receive “a formal grooming policy” in the workplace, 1.5 times more likely to be sent home, and 80 percent more likely to change their natural hair due to workplace rules or expectations. The study surveyed 2,000 women between the ages of 25 and 64.

In Connecticut, Porter said. “I have been one of those Black women.”

If the bill passes this session, Connecticut would be the eighth state with CROWN Act legislation on the books. The hearing, during which almost 100 members of the public also testified on breastfeeding in the workplace, legalizing cannabis, probate court, pension offsets and more, lasted for over 12 hours.

“It is not our job to change hearts and minds,” Porter said. “But what we can do and will do is legislate equity and justice for all.”

“Our Hair Is A Natural Extension Of Ourselves”

In both a press conference Tuesday morning and the hearing itself, dozens of Black women, labor leaders, fellow legislators and CROWN Act advocates came forward to testify in support of the bill. Many arrived with stories of hair discrimination that they, their friends, and their children have experienced in professional and educational settings.

In both a press conference Tuesday morning and the hearing itself, dozens of Black women, labor leaders, fellow legislators and CROWN Act advocates came forward to testify in support of the bill. Many arrived with stories of hair discrimination that they, their friends, and their children have experienced in professional and educational settings.

“Our hair is a natural extension of ourselves,” said Adrienne Cochrane, chief executive officer of the YWCA Hartford Region and a staunch supporter of the bill during the pre-hearing press conference. “And for those of you who think ‘well, it’s just about hair,’ it’s not just about hair. It’s about respect and about being able to rock our crowning glory.”

For 13-year-old Windsor resident Christina Jackson, overt hair discrimination started when she was just eight years old, and one of the only Black girls on her gymnastics team. Jackson recalled coming to practice with her hair in box braids, which she neatly set into two cornrows. While the white girls on her team hit the mat in floppy and loose ponytails, she was reprimanded for her hair, despite the fact that it remained in place during her routines.

She started to ask for chemical straighteners that left her hair brittle and burned. She coveted the ease with which her peers tied their hair up into slick buns for meets.

“I wanted my hair to be like theirs so badly,” she said. “That process ruined my hair and bruised my self-esteem. Bruised, but not broken.”

Now, she said, she has learned to love her natural hair. When she described herself as “full of Black Girl Magic,” Porter beamed and held her hands to her chest, her emotion visible even as she muted herself. She urged legislators to pass the CROWN Act so that she—and so many Black girls like her across the state—don’t have to face the same discrimination that so many have before her.

Similar stories, often spanning generations of workplace hair discrimination, poured in for hours. Rep. Stephanie Thomas, who represents Wilton, Norwalk, and Westport, took the committee back to 1994, when she cut her hair short for the first time. The morning after that big chop, she remembered talking to her supervisor, who “just had this uncomfortable, how-do-I-handle this look” plastered across her face.

Thomas didn’t notice the look at first. She chatted with her boss about the “ease and freedom and my own sense of confidence.” She sat down and prepared to get to work. Then she noticed that her boss was still there, hovering behind her in her cubicle. She was looking at her hair. The boss asked if she was planning to grow it back, expectation at the edges of her voice. Thomas realized that there was an entire discussion beneath the discussion they’d been having.

“It was clear, in that instant, when I looked in her eyes and I said ‘no, I don’t think I’ll ever grow it back’ casually, she had somehow shifted my entire potential career path right then and there in her head,” she said. “She somehow viewed all of my good work differently, and assumed that I wouldn’t fit in as a safe Black, as a palatable person of color, in our core business of convincing wealthy, white philanthropists to make donations to our nonprofit.”

Thomas went on to work for herself. She said that she’d turned out in support on Tuesday —just as she did last March—because she does not want other women and girls to have the same experience that she did. Both she and Porter noted the importance of using their legislative positions, which have historically been denied to people who look like them, to lift up other Black women.

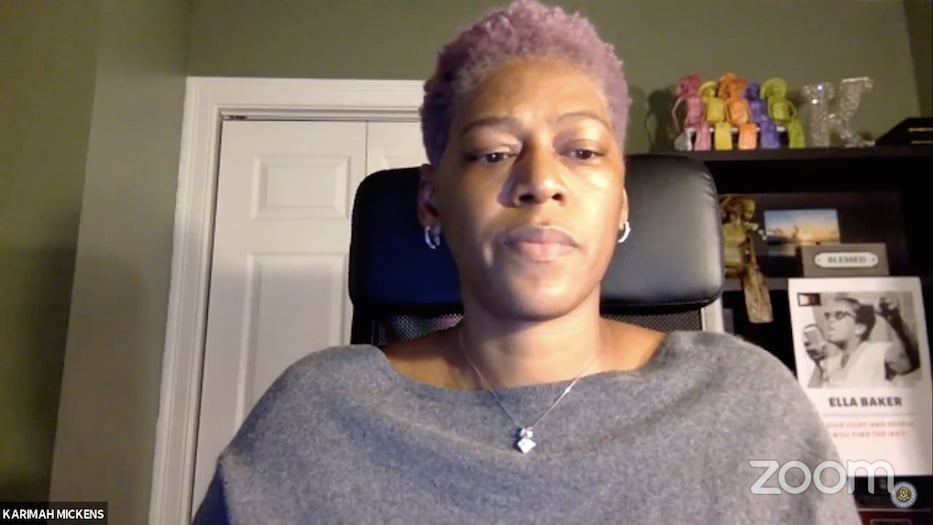

Hamden resident and Ella’s Fund PAC organizer Karimah Mickens Webber said she also experienced that kind of discrimination while working for two decades in corporate America. When Mickens traveled for work, her hair became a source of stress. When she stepped into the board room, it remained one. Only years later did she realize that she’d spent hours of emotional labor on something that should have been her freedom of expression and human right.

“I was already one of the few Black women in the room, and when I dared to show up with my hair in its natural state, it became a huge distraction,” she said. “At the time, I didn’t really think about it. It was just what I did. What I saw other Black women do. Today, I embrace my natural hair fully, and I want other Black women and men and children to do the same if they choose.”

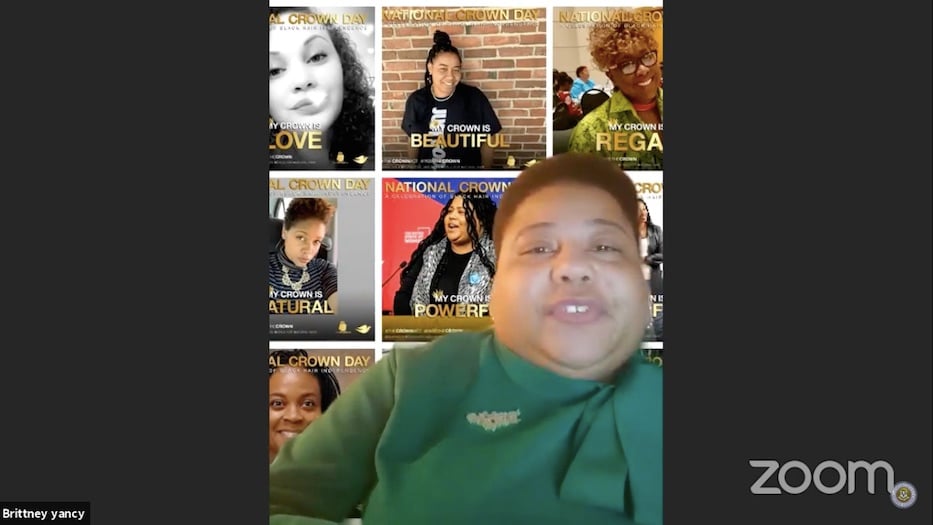

For hours, testimonies came in from all corners of the state. Professor, activist, and Alpha Kappa Alpha soror Brittney Yancey drew a through line from the enslavement of Africans and use of Native American boarding schools to modern-day hair discrimination.

She recalled having a white supervisor put her hands on her hair as if it were part of her role as her superior. She pointed to contemporary hair discrimination among people including Chastity Jones, sisters Deanna and Mya Cook, and wrestler Andrew Johnson.

“The need for us, overwhelmingly Black women, to alter our natural state, is deeply rooted in this legacy of white supremacy, enslavement, Jim Crow, and assimilation in this country. The institution of education in particular has played a historic nefarious role in protecting hair discrimination … Hair discrimination is racial discrimination. And as elected officials, you cannot stand before us and yell Black Lives Matter, put a sign in front of your yard, and yet waver on this bill.”

As a former reporter for Connecticut Public Radio, "proud Black woman" and member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Ryan Lindsay Arrendell recalled working in the State Capitol building for over a year. On assignment after assignment, she received sideways glances when she walked through the halls and into legislative hearings “rocking an afro, cornrows, box braids, Bantu knots, a shaved head, or a head wrap because I chose my freedom over anyone else’s opinion.”

It was part of a pattern she’d seen over and over as a young reporter, she told the committee. When she was in high school, Arrendell wanted to work as a television reporter. By college, she was interning at a station. She recalled having a supervisor praise her clip reel, but suggest she find “a more consistent look.”

“My hair is natural because God, Yahweh, Allah, made me Black, and I will not apologize for it,” she said. “Let me be clear. It is humans, not God, who have tried to oppress, regulate, and legislate what’s acceptable. So do not give Black crowns, our hair, nicknames. Do not touch it. Do not discuss it amongst yourselves. Do not stare. And please, do not try to say that it is my hair that is unprofessional. Racism and white supremacy are unprofessional.”

Almost a full 12 hours into the meeting, Project Resiliency Founder and Director Althea Bates recalled wearing her hair in locs for 14 years, a style she started using when her daughter was a baby and she was pursuing her master’s degree. For years, Bates watched colleagues pull ahead, despite the fact that she had the same level of education and qualifications.

Dressed in a cheery pink that fought the fog of a late-night hearing, she recalled putting her hair into buns to please potential employers. When she started her doctoral work, a white professor asked her “if I would consider changing my hair style, as it may get in the way of my career pursuits.”

“I’m testifying to ensure that young people like my 10-year-old daughter, who has hair pride, will never have to tame, to hide, or to mask parts of her identity. To become whatever she wants to become,” she said. “To me, this bill is about equity of choice. To be who I am, and stand in this space unapologetically related to my crown.”

Legislation? Or Education?

While testimonies received overwhelming praise from committee members, Greenwich Rep. Harry Arora pushed back repeatedly against the need to legislate protections for natural hair. He pointed to his own upbringing in Sikhism, a religion whose fundamental tenets include growing out one’s hair and wearing turbans.

While testimonies received overwhelming praise from committee members, Greenwich Rep. Harry Arora pushed back repeatedly against the need to legislate protections for natural hair. He pointed to his own upbringing in Sikhism, a religion whose fundamental tenets include growing out one’s hair and wearing turbans.

Rather than a legislative issue, he argued that ending hair discrimination is an educational one. Early in the hearing, he also posted on social media to slam Democratic legislators for what he considered "unnecessary over-legislation" to protect basic equity in the workplace.

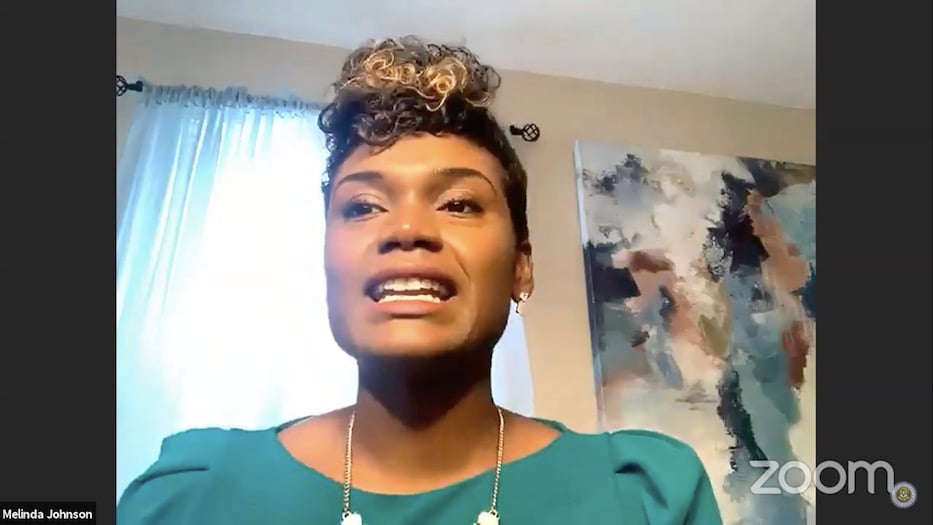

Melinda Johnson, director of community engagement and advocacy for the YWCA Hartford Region, asked him why it couldn’t be both. She looked to an educational system that is still entrenched in European notions of beauty and colonial history. That trend started centuries ago, and still filters into the contemporary workplace. Hair discrimination isn't just about hair, she explained: it is often used as a proxy for anti-Blackness.

“When we’re talking about hair discrimination, we’re talking about so much more than just how a person feels they are able to operate in educational and work spaces,” she said. “We’re talking about how people are limited in their presentation of their full selves in our society. Which means, at the end of the day, it’s our society that’s missing out.

“We’re missing out on the full presentation of genius in the works. We’re missing out on doctors being their best selves at the hospitals. We’re missing out on teachers being their full selves in the classroom. We’re missing out on students learning and receiving and feeling that they are full and complete and enough in our society.”

Calling in from Washington, D.C., CROWN Act champion Adjoa B. Asamoah also made the case for legislative support of the bill, as she has in the seven other states where it has passed. Born and raised in New Haven, Asamoah has helped shape legislative policy for the act, and went on to serve as President Joe Biden’s national advisor for Black engagement.

“There have been countless cases where Black people have been discriminated against for wearing natural hair, and or protective styles including but not limited to braids, locs, twists, etcetera,” she said. “This prominent form includes being fired, passed over for promotions, and having offers of employment rescinded. It impacts our upward mobility, and has been the reason far too many of our children have missed school and had negative educational experiences.”

“The African aesthetic is beautiful, and it must be lifted and valued,” she continued. “This issue of narrow beauty standards in America continue to promote inequity, injustice, and discrimination in the workplace and in schools and it warrants a legislative fix."