Stitching the Revolution runs through August 25, 2024, at the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury. Jacquelyn Gleisner Photos.

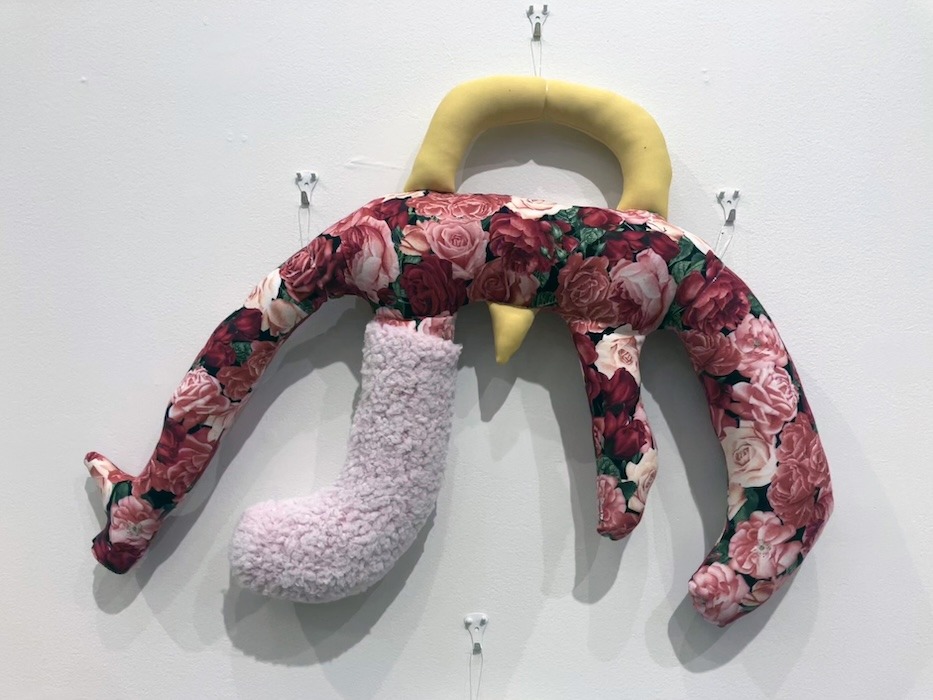

A floppy gun made from floral and fuzzy light pink fleece is not the first image that comes to mind when thinking about quilts—but that’s the point. Natalie Baxter’s Mama Rose (Warm Gun) and Play Date (Warm Gun), both from the artist’s “Warm Gun” series, subvert the masculinity of firearms. Instead, there’s a feminine materiality: a melange of unlikely fabrics sewn together and stuffed loosely with polyester filling. The flaccid forms render the guns impotent and slack, a long way from the uniformly strong language of gun advertisements and ephemera for Second Amendment enthusiasts.

The dissonance of Baxter’s wonky guns amplifies the crux of Stitching the Revolution: Quilts as Agents of Change, on view at the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury through August 25, 2024. Organized by Chief Curator Keffie Feldman, the show aims to position the practice of quilting (and a generous interpretation of quilting-adjacent artforms) as a conduit for political activism and meaningful cultural reflection. Here, the crisis of craft versus art (a hangup for acolytes of Modernism) takes a backseat to the celebration of these objects, zeroing in on their power both to comfort and challenge, sometimes simultaneously.

In Stitching the Revolution, historic quilts mingle with contemporary takes on the medium, with a multitude of objects spread across two large, densely-hung rooms. Generous wall texts guide a viewer’s experience of the works in an asynchronous presentation, grouped into three broad categories: Form, Material, and Pattern and Figuration. The space feels exciting and energized, if cramped.

Baxter's mama rose warm gun, 2022.

You don’t need to get too far into the show to understand that Stitching the Revolution construes the craft or technique of quilting liberally. Traditionally defined as two layers of fabric with batting in between, quilts are often associated with bedding, though they are not always strictly utilitarian objects. Throughout history, textiles have been a significant outlet for women and non-white makers, those without entry to “more official channels,” according to the title wall text.

With this subtle omission of bias, the compounding influence of class, race, and gender on the medium becomes an important subext within the exhibition: Who makes quilts and what does adapting this form for a contemporary artist mean? Given the immense umbrella of arts spawning from or inspired by quilts, certain works in this exhibition move closer to the medium, while others have more tenuous connections.

Some works in the show do not contain fabric at all. Laura Petrovich-Cheney’s Devotion uses pieces of reclaimed wood in a pattern that references a double wedding ring quilt. The salvaged wood correlates to the practice of reusing scraps from other textiles and repurposing discarded fabrics rife throughout quilting histories.

Another non-fabric work, do you ever really wonder? by Ghost of a Dream (Lauren Was and Adam Eckstrom), is composed of an intricate collage of lottery tickets. The massive, multi-panel mixed media work might seem to resemble a quilt at first brush, though the precise reference point is the floor of the Oratorio of Sant Maria della Vita. That the tile design in this Baroque and Rococo style church in Bologna, Italy seems akin to a quilt pattern exposes the flexibility of the medium—and perhaps the curator’s agenda to clump works together superficially: Aren’t all crafts (and crafters) related enough? (See Desmond Beach’s magnificent woven portrait Perfectly Poised for another similar example of broad-brushing.)

Other works use fabric sparingly. DARNstudio’s Robes B/W is made from an arrangement of matchbooks and recycled felt. Bhasha Chakrabarti’s painting Maya and Neera on a Fake Gees Bend Quilt depicts two nude women of color, resting on a textile with bold stripes and squares. Their backdrop—a field of geometric stripes and checks embellished with real fabric elements—seems to recall the oft-cited aesthetic overlaps between the quilting group in a tiny, historically Black town in Alabama and the white, male artists of the Color Field Painting movement. It’s not difficult to guess which of these lots is relatively new to the American art history canon and which one is dogma.

Given the pomp in this show—beads, faux fur, sequins, and glittery surfaces abound—Crazy Quilt by Flora Morgan and Laura Morgan or Mary Thompkins Adams Pritchard’s Patchwork Quilt are unlikely stunners. Yet the investment of time and care in the more conventionally pieced textiles shine through.

Another standout is Wally Dion’s diaphanous curtain Pollinator Quilt. With its purple and hot pink eight-pointed star at its center, this massive and ethereal “quilt” can be seen from many vantage points within the show. At times, its gorgeous transparent fabrics overlay other works with similar designs such as Susan Hudson’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Children’s Journey to the Milky Way—the repeating motifs evince how the lexicon of quilting has been passed between cultures and times.

In Hudson’s quilt, the traditional North Plains Star pattern reappears with a figurative scene. Children walking along a path marked by small crosses hint at the prolific and systemic violence of residential schools for Native American children.

Back near the entrance to the show, Baxter takes on another loaded symbol—the American flag. On the title wall, Aggressive Nationalism (Bloated Figure) has a soft pink metallic fringe border along all four sides of the petite, overstuffed flag. Shiny purple stripes contrast with a blue and white patterned fabric, while the stars of the design have been swapped out for illustrations of faceted jewels and bling in upper right corner.

With is immediate appeal, Baxter’s flags—there are two others on an adjacent wall—underscore how nimbly the artists in this boisterous exhibition can leverage pieces of a rowdy and expanding medium to suit their own needs in this country’s evolving history, uncomfortable flashes of patriotism and painfully politically overt moments notwithstanding. Still the strength is the diverse range of artworks and artists on view, which collects over 200 years of sustained engagement and upended expectations.

Stitching the Revolution runs through August 25, 2024, at the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury.