Frances "Bitsie" Clark | Arts & Culture

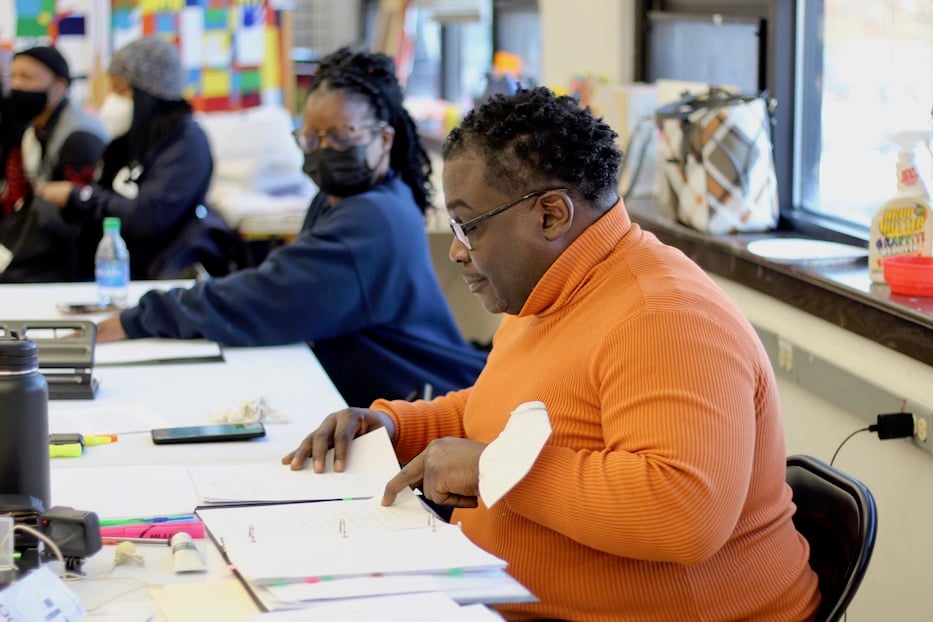

Driffin at a rehearsal in a rehearsal for Death By 1,000 Cuts: A Requiem for Black and Brown Men. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

An early-career video artist and veteran New Haven playwright are the latest recipients of $5,000 grants from the Bitsie Clark Fund for Artists. Now both are using the funding to explore the way they—and others—look at the world around them.

Those artists are Jake Gagne and Steve Driffin, whose work ranges from psychedelic, pensive experiments in video animation to guerrilla street theater. On Monday, the fund announced that the two are its 2021 awardees in a video on its website. Both expressed their surprise and gratitude for the funding, which will support current and evolving projects.

Finalists include visual and installation artist Faustin Adeniran, composer and musician Skyler Hagner, and cellist and Dignity Music founder Ravenna Michalsen.

“When I got the letter from the Bitsie Fund, I wept,” Driffin said in a phone call Tuesday morning. “It was like I'd won the Oscars. I was so moved by it. It was personal for me. It was from someone that I knew, someone that I was fond of, and when I received it I was so humbled.”

The fund honors Frances “Bitsie” Clark, a former director of the Arts Council of Greater New Haven whose pioneering legacy includes creating the Audubon Arts District, serving on the New Haven Board of Alders, and providing advice and support to hundreds of artists in the region. At 91, Clark has continued to advocate for the arts and artists in her retirement.

Grants are administered by a committee including Clark, Mimsie Coleman, Kim Futrell, Robin Golden, Stacy Graham-Hunt, Betty Monz, John Motley and Maryann Ott. Coleman, Golden, Monz and Ott launched the fund in 2018 to honor Clark’s mentorship.

For Driffin, who has been making theater in the city for 30 years, the funding marks a full-circle moment. In 1991, he had just moved to New Haven after college, and was living in the city’s Newhallville neighborhood. Around him, he saw a city ravaged by the crack epidemic. It led him to write Yo’ Street, a large ensemble work “showing how the community used to be before drugs infiltrated it.” It is one of the only works he has both written, acted in and directed.

“The concept behind the title was, this can be any street in America,” he said. “Drugs have impacted communities in chapters. In the 90s it was the crack epidemic that decimated the Black community. Now, it’s more common that we see meth, which we treat with a different hand.”

Working with Bishop Theodore Brooks, he staged it in front of Beulah Heights First Pentecostal Church on Orchard Street—then one epicenter of New Haven’s crack epidemic. When actors began to perform, Driffin didn’t know what to expect. Passers-by stopped what they were doing and stayed to listen. Some moved in close so that they could see the actors, and began talking back as if it was an outdoor church service. What started as a trickle became dozens of people.

In the next months, he applied to the Community Foundation for Greater New Haven to secure grant funding for a second performance. He worked with James Hillhouse High School to stage it (he praised then-Principal Lonnie Garris, who opened up the school without hesitation). When a third one followed at the school that October, Clark happened to be in the audience. She became one of his first and most steadfast supporters.

Black (Rodney Moore) and Gold (Sharmont Little) in a rehearsal for Death By 1,000 Cuts: A Requiem for Black and Brown Men. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

“That was the beginning of Bitsie and I,” he said. The two kept tabs on each other as Clark continued to support New Haven’s artists, and Driffin pumped out dozens of scripts, becoming a well-loved mentor and prolific writer in the community. Last year, he doubled down on his writing, with projects that ranged from a show at the Legacy Theatre in Branford to his powerful Death By 1,000 Cuts: A Requiem for Black and Brown Men at the The Lab at ConnCORP and Quinnipiac University.

“People heard me say I was betting on Steve this year,” he said with a laugh. It resulted in grants from both the Bitsie Fund and the Connecticut Office of the Arts, which awarded him another $5,000 for the project. Driffin, in turn, was able to formally reconnect with Clark after the quiet and isolation of the pandemic.

“She is a giant, a goliath in the arts,” he said. “ She is such a freakin’ trailblazer. When I grow up, I want to be like her.”

He said he is excited to be bringing Death By 1,000 Cuts to the Whitney Center, where Clark lives, for three intimate performances later this month. In honor of where he started, he also plans to bring the play to the streets this summer, and is hoping that it will be able to bring its message beyond New Haven.

“There’s different kind of energy and power doing that ,” he said. “There’s an audience that won't come to theater, which is why I started doing street theater. I think it's fitting to pay homage to where it all started. So that's important to me.”

Photo Courtesy of the Bitsie Clark Fund for Artists.

Gagne, meanwhile, is using the grant funding to purchase and experiment with new equipment for their video art. Born and raised in Simsbury, they began their arts education in music, with a 12-year study of the classical bass that ended in college (they still make music under the moniker Skeleton Yaks). Video, influenced partly by an interest in paranormal or ghost images, is now their main medium. In the past years, it has led them to experiment with Blender, an open-source 3D animation program.

“People use it to make everything from weird art to Pixar movies,” they said with a little laugh in a phone call Tuesday morning. In a recent video of theirs titled Test Tube Mirror Dialectic (Parts A/B/C), the frame opens on a grainy swirl of images, synth-soaked music rising as shapes shift over it. On a split screen, they become the fuzzy black and white of tv static, then bouncing of sound waves and soft, luminous shapes.

Sometimes, Gagne leaves the viewer with a deep blackness, punctuated with pulses of light. Others, the synthy music is back, scoring a flood of psychedelic colors as they blink in and out.

With support from the Bitsie Clark Fund, Gagne will be able to work on a new video project based on a recent inner-ear surgery to remove a recurring growth. After the surgery, they were extremely sensitive to sound—and equally interested in that sensitivity. It led them on an exploration of identity, self-perception, and a shifting understanding of their body.

“The body is a lot more sensitive of an instrument than it's made out to be, and it has a lot more possibilities than it's made out to have,” Gagne said. “I think there's a metaphor of searching for something beyond what you have access to.”

They added that the grant is a financial boon as much as a creative one—gear is expensive. When they received the funding, they were able to buy a Moog synthesizer, speakers, headphones, a microphone, and a new SLR camera. They are hoping to move into a formal studio space later this year.

“I was really surprised, honestly,” they said. “I've had an art practice for a long time but never applied for anything like this. I am an early career type of maker, and already the support has opened up a lot of new avenues in my practice that I didn't foresee.”

Learn more about the Bitsie Clark Fund for Artists here.