Arts & Culture | Film & Video | Yale University | Comedy | Arts & Anti-racism

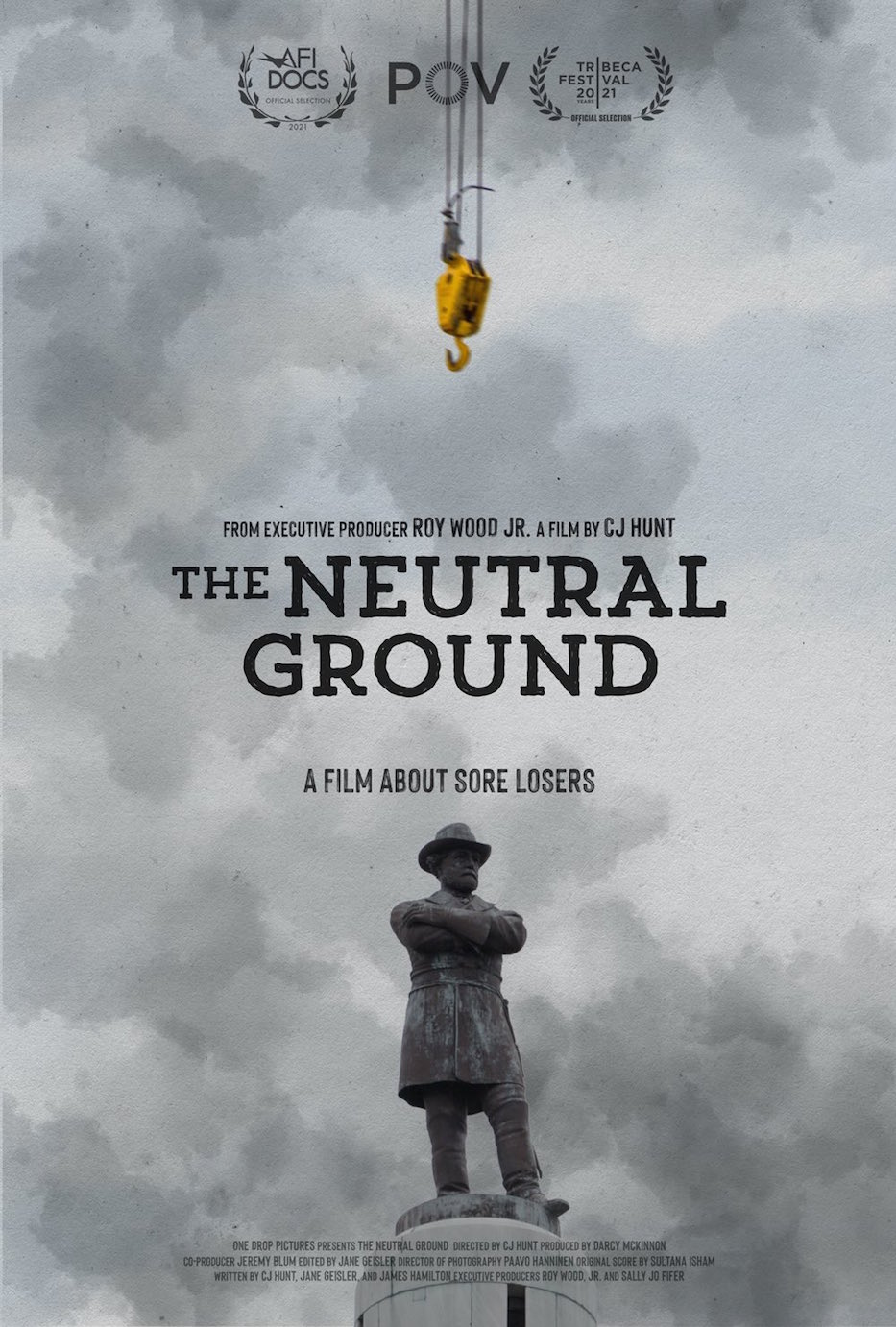

Courtesy CJ Hunt.

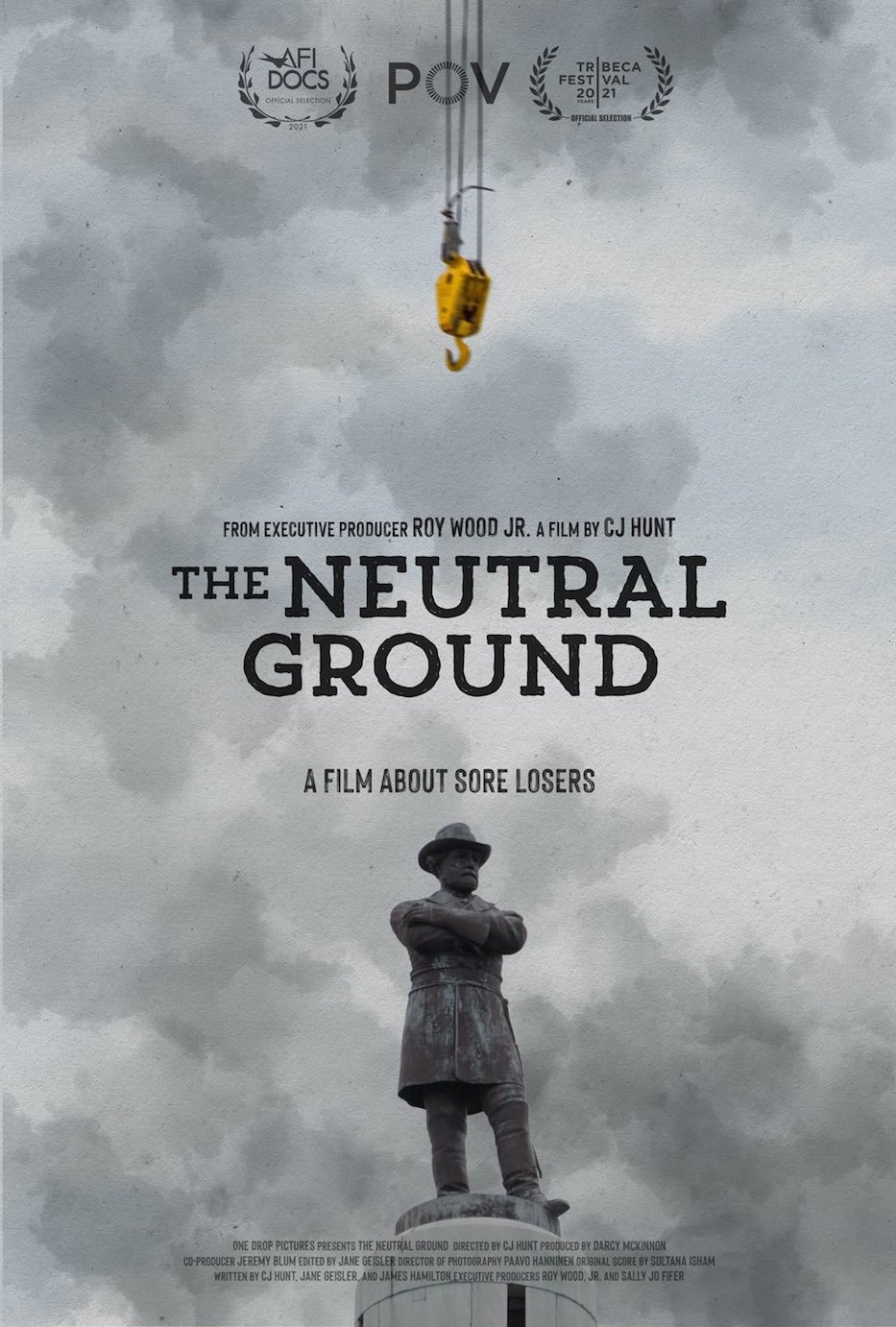

Courtesy CJ Hunt.

The film panned over a harsh portrait of Alexander Hamilton Stephens, vice president of the Confederate States of America. A narrator analyzed Stephens’ infamous Cornerstone Speech—and noted that Stephens had some “dry ass lips.” In the virtual audience, Sterling Professor of History, of African American Studies, and of American Studies David Blight “howled out loud” at the quip.

Blight is the director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University. And he had never heard a summary of Stephens’ address quite like this.

Nominated for a 2021 Critics’ Choice Award for best documentary narration, CJ Hunt’s 2021 film The Neutral Ground is a satirical documentary that follows the 511-day process to remove four Confederate monuments of Robert E. Lee, P.G.T. Beauregard, Jefferson Davis, and The Creation of the Battle of Liberty Place in New Orleans. Hunt, currently a field producer for The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, lived in the city teaching English to middle schoolers while he watched the process firsthand, and was inspired to make the film.

On Sunday evening, Yale University’s Schwarzman Center hosted a virtual watch party of Hunt’s film as a part of “Memorializing History: A Conversation About Monuments, Truth, and Justice.” The approximately 50 attendees participating in the event were able to comment on the film on the Ovee platform in real-time. Following the virtual screening, Hunt participated in a conversation with Connecticut-based artist and educator Allison Minto, Senior Lecturer in African American Studies and Film & Media Studies Thomas Allen Harris, and Blight.

“I love the phrase of the Janus face,” Hunt said. “The comedy is that all these white people refuse to accept the truth [about white supremacy and the Confederacy]. Let's laugh at that. Now, let's take a minute and realize that the tragedy is that all those white people refuse to accept the truth.”

The Neutral Ground emphasizes how white men, women, and children had control over their own historical narratives through the myth of the “Lost Cause,” which combined nostalgia for the Confederate past with a collective forgetting of the horrors of slavery—particularly its “daily violence [and] idea that man’s labor is not his own,” according to an interview with historian Christy Coleman in the film. White Southern women would fundraise and organize the construction of Lost Cause monuments to the Confederate dead in graveyards, and at the dedication of such monuments, children would stand in a certain formation so they created a living Confederate flag.

Lost Cause rhetoric was not simply focused on falsely valorizing the Confederate dead in the South, the documentary noted. The entire nation used this rhetoric to reconcile white Northerners and white Southerners. During the discussion section, Blight mentioned that Yale University built its own Civil War Memorial, dedicated in 1915 at the “heightened triumph of lost cause ideology,” in part in order to attract “Southern boys” back to Yale. It was the same impulse that led the university to name a college after John C. Calhoun, the South Carolinian who ardently defended enslavement during his lifetime, decades after Calhoun's death.

The film argues that such rhetoric, and memorials to such rhetoric, exerts control over the space. The Confederate statues in New Orleans featured in The Neutral Ground stood in places supposedly for the community, just as the Schwarzman Center, one of the “most-trafficked” spaces at Yale according to Blight, houses the Civil War Memorial. The center, which was only recently opened, is also kind of modern monument itself, named after Blackstone CEO Steven Schwarzman, a former business advisor to Donald Trump and corporate landlord whose $150 million gift to the university came with naming rights.

The Neutral Ground begs the question, what is to be done? After all, the Civil War Memorial still stands in the Schwarzman Center. While the four New Orleans Confederate monuments followed in The Neutral Ground were eventually dismantled, that process took 511 days. And in New Haven, people from across the East Haven town line are still fighting the decision to remove a statue of Christopher Columbus from Wooster Square last year.

“What are ways that we can actually uplift, actual examples of rebels that we can be proud of?” Hunt asked. “What are ways that we can show Black and Brown folks that we are part of this [American] history [and not expend energy] trying to have some sort of Green Book scenario where we convince a racist that racism is bad?”

In the conversation following the screening, Hunt described the “brave act” of Corey Menafee, a Black dishwasher who smashed a stained glass window depicting an enslaved person carrying bales of cotton in Yale’s Grace Hopper—formerly Calhoun—College. Protests that followed his act and Yale’s subsequent gag order on Menafee ultimately pushed the Yale to change the college’s name. To Hunt, this was a remarkable paradigm shift. As The Neutral Ground documented, he had to engage in debates with “gatekeepers and active white supremacists” in order to make a “bargain.”

“We are no longer asking for permission,” Hunt said.

Later in the conversation, Minto and Hunt discussed the unusual or unique qualities of art. While Hunt noted the “design problem” of “weaponized” and mythologized Confederate art that “will have an effect on people’s lives for hundreds of years,” Minto said that art can mythologize and world-build in positive and restorative rather than harmful ways.

“It’s important that artists are not historians/journalists,” Minto said. “[They] can operate with imagination. Artists should be mindful of how memory shows up in the body, the mind. You can have something happen to you but it’s not recorded, it holds a personal truth..”

To end the discussion, Hunt posed a series of questions to the audience and Yale University as a whole and emphasized the importance of transitioning from rhetoric to action. Hunt himself hopes to work with educators to screen the film in classrooms across the nation.

“How do we resist white supremacy and curriculum?” Hunt asked, alluding to debates around Critical Race Theory that have been raging across the country, and as close by as Guilford. “How do we break the window, so to speak? And then how do we plant a flag for our ability to tell the truth when that is literally under attack in the law right now?”

CJ Hunt’s documentary The Neutral Ground, a part of the PBS Point-of-View Documentary Series, is free to watch until Nov. 30, 2021. Above is an interview with Babz Rawls-Ivy of WNHH Community Radio.