Downtown | Immigration | Politics | Arts & Culture | Theater | Unidad Latina en Acción | COVID-19

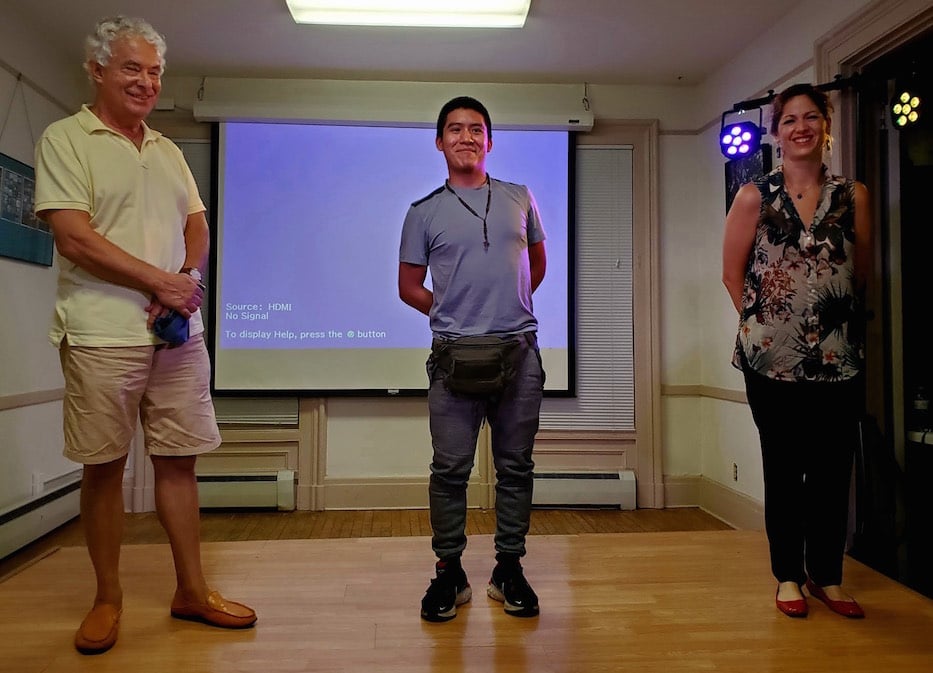

| Sandra Gumuzzio and the children interviewed thank the audience. Sandie Luna Photo. |

A mother in New York calls her mother back in Guatemala. After years of working, she can finally afford to bring her two daughters to the United States. The grandmother readies the girls and sews the mother’s cell phone number on the inside of their dress’ collars. These dresses are their only change of clothes for the entire journey. Under no circumstances, including sleep or bathing, are they to ever take off these dresses.

A man will come and guide the girls from Guatemala all the way to New York. Don’t be afraid, the grandmother assures them. There is nothing to be afraid of.

The anecdote recounted by Valeria Luiselli (Sandra Gumuzzio) ends. This story, just like countless others from unaccompanied minors who travel from their home countries in Central America to the United States, has a beginning. It does not have a known end.

It is a part of los niños perdidos: una pieza en 20 preguntas, a work that does not provide answers (in fact, it refuses to do so). In the work, a monologue recited by Gumuzzio weaves in and out of video footage of eight members of Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA), together ages eight to 23, answering the questions.

Saturday, the adaptation of Valeria Luiselli’s Dime cómo termina: un ensayo en cuarenta preguntas (Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in 40 Questions) opened at the New Haven People’s Center on Howe Street. The 40 questions is a reference to the questions Luiselli translated and asked undocumented Latin American children facing deportation. It came to the People’s Center as a collaboration between ULA and the Bronx-based ID Studio Theater, which also put on Casa Grande at Bregamos Community Theater last year. All performances were in Spanish.

As much as the work is a theater production, it is first and foremost a celebration of the children and their families, said Director Germán Jaramillo.

“Theater at its core is a celebration of sorts,” he said. “But this work celebrates the children in this space and beyond.”

The adaptation was developed over the course of a year by Linn Cary Mehta with permission from Luiselli. Cary Mehta saw ULA and New Haven as the ideal group to collaborate with because of Studio ID’s longstanding partnership with ULA. The group had been working with the children since 2014, hosting workshops and various other programming.

| Erick Sarmiento Photo. |

At first, Jaramillo had concerns about adapting Luiselli’s novella. The original work features a documentary-style series of essays about the children, without a linear arc or established set of characters. He and Cary Mehta decided that a monologue would be the best adaptation, to concentrate all of the stories and give a body to the dozens of voices.

In the early drafts, Cary Mehta included testimony from three children. After seeing the testimony paired with the script, Cary Mehta knew that she needed to keep adding more testimony from young people.

“It became the most moving part of the script,” she said, “With their voices it becomes timeless.”

Luiz Diaz, one of the interviewees, felt it was important to share his story because of the recurring nature of the migration crisis.

“For me, it was important to show the suffering that happens just to get here,” he said. “Even though it has been years since I came as a kid, it is still happening.”

The interview footage and additional photographs transform the work into a grounding experience—Cary Mehta deliberately places the unaccompanied minors’ narrative within an ongoing global conversation. At one point, an image of Alan Kurdi, a 3-year-old Syrian boy who drowned off the coast of Turkey, is projected onto the screen. The image went viral in 2015 as a symbol of the Syrian refugee crisis.

Just before the image appeared Saturday, the interviewed children recounted their journeys across Mexico riding La Bestia, a network of freight trains that run from the southernmost border with Guatemala to the United States-Mexico border. More than 500,000 people ride La Bestia every year many of whom are from Central American countries.

The children recounted the struggle of staying awake for entire days, too afraid to sleep and fall off the top of the train. Some stood in between freight carts holding on for hours until a spot on top of the cars opened up.

Jaramillo said he believes it is impossible to discuss localized current migratory patterns without a global perspective on the history of migration both present and future.

|

Gumuzzio performing Miguel Hernandez's Eulogy. Erick Sarmiento Photo.

|

“The migratory crisis is the norm,” he said. “All of the migration from Africa to Europe, [the] Middle East, and so on, is all interrelated. The migratory crisis is an essential issue in our modern times.”

In one of the early vignettes, the children are asked the first question from the form, “Why did you come to the United States?”

Their answers vary widely across age and gender. Some of the younger members simply respond that their parents told them to do it. The older interviewees describe facing overwhelming economic hardships or threats from gangs such as MS13 and Calle 18.

One of the girls recounts her father physically abusing both her and her mother. The mother eventually left for the United States leaving her behind. The local gangs began to threaten her in addition to her father’s abuse, leaving her with no option but to flee and find her mother.

The United States government asylum process favors the most violent of circumstances. At one point in the show, Gumuzzio explodes with frustration, begging the children to give her the most violent answers possible because it will bolster their case for asylum. But they are children and do not understand the weight of their answers.

The children are asked: “Have you ever had any problems with your government’s country?”

Gumuzzio poses the question. The boy in the video does not understand. She rephrases the questions. He still does not understand. She smiles and forces enthusiasm behind the question hoping that her warmth might unlock something.

Often these minors speak Q’anjob’al, Kaqchikel, Mam, Chuj and other Indigenous languages. They either speak little Spanish or have learned it as a second language. In the process of translating, Gumuzzio considers how she can break down formal English into child friendly Spanish which a child with limited Spanish could answer.

The problem not only lies with the questions but the children. Their stories are convoluted, scrambled, and sometimes torn beyond recognition. They might have moved various times to avoid conflicts or not have seen their parents since their birth. It is impossible to impose a linear narrative on their stories when they’ve never lived linear lives.

As the questions fall apart, the truer criminal nature of the questionnaire unfurls. The goal was never to build a robust defense but mount cases for deportation against them and their families in the United States.

“Do you have any close family members whom you will live with in the United States?” she asks. “What is the migratory status of this relative?”

| Erick Sarmiento Photo. |

An honest answer could lead to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) tracking down and deporting their family members. A “no” means the child has a weaker case for asylum compared to children who do have a relative.

In posing these impossible to answer questions, the play succeeds in exposing the labyrinthine nature of the United States immigration system, in which very few escape and most are trapped inside. John Lugo, community organizing director of ULA, said he believes the work successfully captures the struggle of encountering the united states legal knowing that it will be against you.

“The work shows how criminal it is to migrate to this country,” he said. “The system is built on privilege, and those without it have to suffer.”

ULA representative Megan Fountain emphasized the importance of researching the history of Central American countries and learning how these countries came to be hotspots for emigration. She cited the United States history of backing right-wing authoritarian military regimes over left-wing leadership in Guatemala and Honduras.

In 1954, a US-backed coup overthrew the democratically elected president Jacobo Arbenz. The overthrow resulted in a bloody civil war with more than 200,000 civilian casualties and lasting impacts on the country’s economy.

Cary Mehta also pays her respects to the countless children and adults who die before ever reaching the border or leaving their homes. She includes an excerpt from Miguel Hernandez’s Eulogy for Ramón Sije, Hernandez’s childhood best friend. In 2010, members of the Zeta drug cartel killed 72 Central and South Americans who were traveling to the United States.

Saturday Gumuzzio embodied Hernandez' eulogy, as she clawed at the ground filled with grief and anger trying to dig up her best friend’s body. Each swipe was more desperate and wild than the one before it. As she dug, Lucia della Paolera sang the poem’s crushing lines, “I want to dig up the ground with my teeth… and kiss your noble skull.”

She reached Sije’s body and cradled the body in her trembling arms. Shaking, she hugged the imagined body one more time before putting it to rest for the last time.

Like the other cast members, Gumuzzio has a personal connection to migration. Two years ago, she planned on abandoning her life and traveling to Greece to aid with the refugee crisis long-term. Instead, she began looking for projects that told the stories of child refugees, and thinking how she could elevate those through theater. When Jaramillo reached out about the part, she felt it was the perfect opportunity for her to merge her personal interests with her acting.

“The importance of the work is that it be told over and over and over,” she said. “If we don’t, it will be forgotten.”

By refusing to answer any of the 20 questions, the work leaves space for the viewers to consider their own journeys and ends. The goal will never be to answer the questions, but to continue posing them countless times as an act of remembrance for the tens of thousands of unaccompanied minors worldwide who undergo these perilous journeys without a guarantee of safety.

Los niños perdidos (Parte 2)¿Por qué viniste a los Estados Unidos? Todos tenemos una historia que contar ... Esta es una de las preguntas centrales en "Los niños perdidos: una pieza en veinte preguntas" - un monólogo adaptado del libro de Valeria Luiselli, basado en sus experiencias trabajando como traductora voluntaria para niños migrantes que buscan representación legal en los cárceles de Inmigración. Esta obra de teatro incluye entrevistas con jóvenes y niños migrantes que forman parte de Unidad Latina en Acción. Les agradecemos a los niños y a sus familiares que presenciaron el estreno de la obra el 29 de agosto de 2020 en el New Haven Peoples Center. Los Niños Perdidos de Valeria Luiselli Presentada por ID Studio Theater & Unidad Latina en Acción - ULA Adaptada por Linn Cary Mehta Dirigida por German Alberto Jaramillo Gallego Actuación: Sändrä Gumuzzio Música original: Pablo Mayor & Carlos Durán Arte visual: Montserrat Vargas

Posted by Unidad Latina en Acción - ULA on Saturday, August 29, 2020

To watch the full performance, click on the embedded video.