Arts & Culture | New Haven | Community Heroes | Film & Video

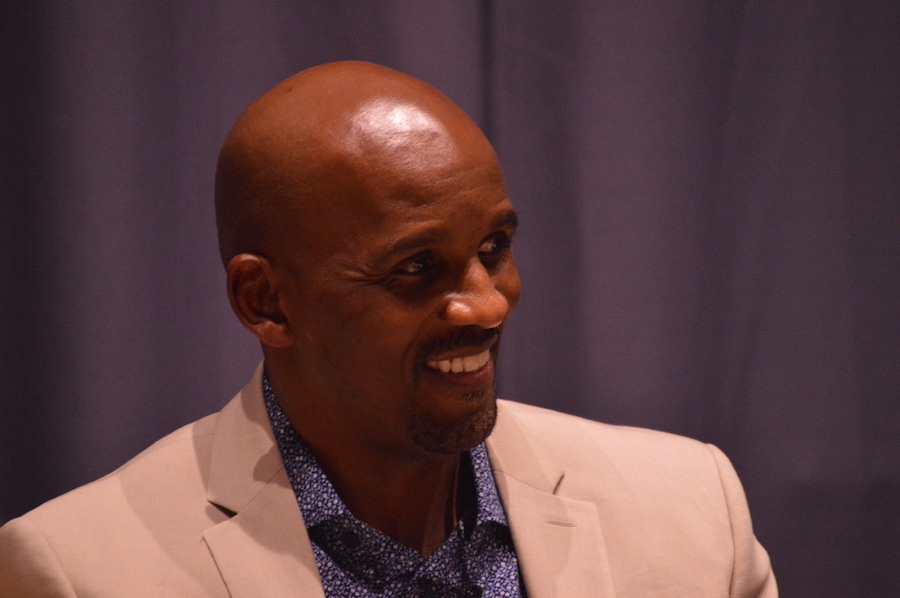

| Lewis at the event. Karen Marks Photos. |

Scott Lewis’s story begins with a stoplight. It ends 20 years later, when he is released from prison after being falsely convicted for a double homicide. Now, audiences get another look at everything in the middle.

Saturday evening, over 200 people filed into Henry Luce Hall at Yale University to watch 120 Years (watch the trailer here), a new documentary on Lewis’ case, wrongful conviction, and journey to freedom from Yale undergraduates Keera Annamaneni, Lukas Cox, and Matt Nadel. It tells the story of Scott Lewis, a New Haven man wrongly convicted of murder in 1990, and given a 120-year sentence in 1995. He remained in prison for almost 20 years, released in 2014. Last year, the city settled a wrongful conviction lawsuit that awarded Lewis $9.5 million. In the intervening years, he spent two decades of his life fighting authorities on a crime he didn’t commit.

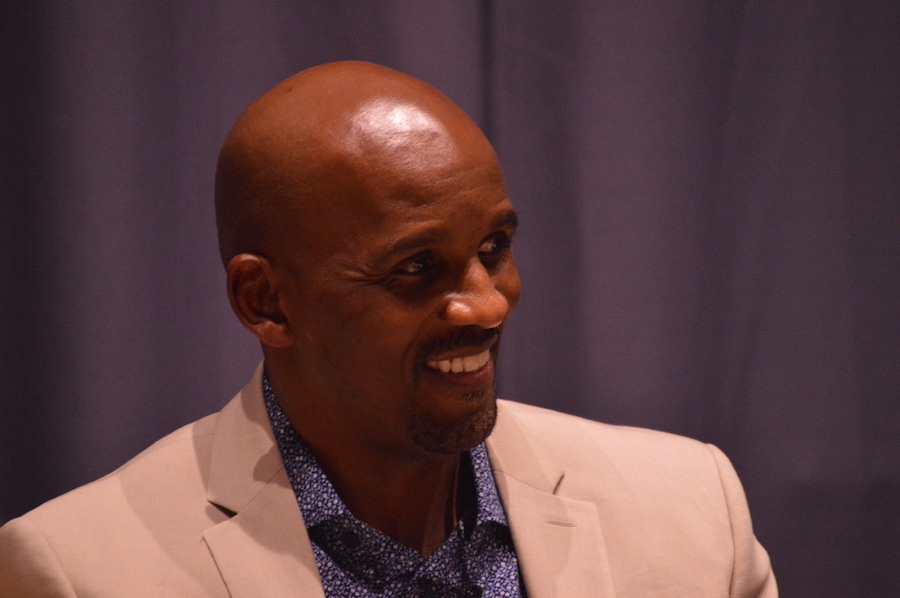

After the screening, Annamaneni moderated a panel that included Lewis, Columbia Law School Vice Dean Brett Dignam, Connecticut Innocence Project Directors Vanessa Potkin and Darcy McGraw, and recent exoneree Bobby Johnson. Each has played a kind of role in the history and aftermath of Lewis’ imprisonment: Dignam and her team were representing Lewis when he won an appealed case in 2014. The Innocence Project has fought with Lewis and Stefon Morant for two decades. And Johnson was wrongfully convicted of murder in 2006, for which he received a 38-year jail sentence. Nine years later, it was declared a wrongful conviction and he was released.

The film begins by introducing us to Lewis, and to his story. In 1990, Lewis was 25 years old with a history of drug dealing, but but no criminal record to suggest violence. In fact, he was turning things around—he had declared an intention to stop dealing and start a career in real estate. Then one night, the cops pulled him over for turning on a red light. He was arrested for a double homicide that had taken place in early October of that year, and charged with the killing of former Alder Ricardo Turner and Lamont Fields in New Haven’s Hill neighborhood. In spring 1995, despite evidence and an alibi that suggested Lewis’ innocence, he was tried for and convicted of a crime he didn’t commit. (Read Paul Bass’ decades of reporting on the case here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.)

| Recent exoneree Bobby Johnson. Brett Dignam is pictured in the background. |

In the documentary, Lewis recalls Detective Vincent Raucci telling him during his processing, “You should have never stopped selling drugs in Fair Haven.” In fact, the reality was more complicated: Raucci, a decorated cop with the New Haven Police Department who was then called a community hero, trafficked cocaine in the city during that time. He made up facts for the case. And ultimately, he cost Lewis almost two decades of his life.

Lewis said he understood that the system was loaded against him. There was evidence of his being at work during the time of homicide. There were previous complaints against Officer Raucci. They fell on deaf ears. Instead, Lewis spent years in prison learning the logistics of his own case and the law.

“I told myself I wasn’t in prison, I was at work,” Lewis recalled in a post-screening panel. Watching prison guards come in and work 16-hour shifts inspired him—with some irony—to work his mandated hours a day and then spend more time studying his case.

After his workweek, Lewis received a payslip with his expected year of release in the 22nd century.

“But I knew that was my reality, not theirs,” he said. In what he joked was a characteristic move as a “hard-headed” person, Lewis decided all he had to do was work hard enough to clear his name. Upon lowering his own bond and getting an appeal through, Lewis worked with Dignam and law students from Yale and Columbia Law Schools—his “legal angels”— to develop his case and push it through to his eventual release in December 2013. While Lewis has been cleared of the charges, he still carries a felony conviction that affects his life outside of prison.. So does his co-defendant Stefon Morant, who was released from prison in June 2015.

| Vanessa Plotkin. |

“I don’t think the hardest part is over,” Lewis said. He was referring, he said, to rebuilding his life and relationships after his sentence, as well as fixing a system rife with false convictions. Ten percent of inmates are estimated to be wrongfully convicted of felony crimes, even in cases such as Lewis’s where evidence is collected but defense does not pull through.

When asked if they thought the justice system had improved since Lewis’s charge in 1991, Dignam and Connecticut Innocence Project director Vanessa Potkin gave a disappointed but emphatic “no.” McGraw asserted that she herself had been a prosecutor, which gave her insight to deep issues in prosecutors offices. Prosecutors, to her, wield a huge amount of power, usually under the assumption that “if there’s smoke, there’s fire … if he didn’t do it, he did something else.”

“I don’t think any prosecutor has ever been disciplined,” McGraw said. Still, Lewis had to work to believe in a system he knew was corrupt to get out, he explained when asked how he kept from feeling angry in prison.

Dignam and Lewis reminded attendees that those actually responsible for the homicides were never found or convicted. In working to have his own conviction reversed, Lewis said he was also fighting for the victims and said that resolving wrongful convictions was also a “public safety issue.”

After the screening Nadel told attendees, “I hope that you do your best to be skeptical.”

And then, “It’s about trying to relearn each other.”

Donations from the screening and panel went towards the Innocence Project, which uses DNA testing to exonerate the wrongly convicted and works to reform the criminal system. Annamaneni invited others in the auditorium who had been wrongly convicted to stand, showing that Lewis was not a unique case even just in New Haven. On the panel, Lewis and exoneree Bobby Johnson reflected on trying to catch up with the expectations and evolution of family members, readjusting to a new social landscape, and coming to terms with being older.