Culture & Community | Downtown | Arts & Culture | History | trinity church on the green | Arts & Anti-racism

Top: Rev. Luk de Volder talks to students. Bottom: The stones are placed at the church. Al Larriva-Latt Photos.

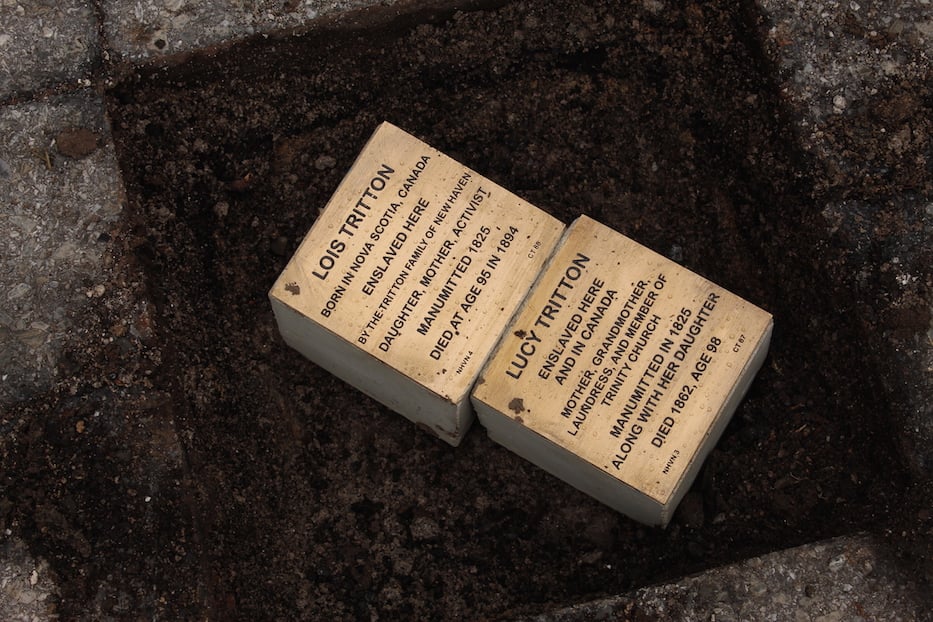

At the steps of the Trinity Episcopal Church on the New Haven Green, a dozen New Haven private middle schoolers in dress clothes crouched around two metal-plated stones. To the right, colorful posters displayed family trees, timelines, and key word definitions. The students leaned closer, studying the stones.

“Lucy Tritton enslaved here," read one. “Lois Tritton enslaved here,” read the other. The sounds of the New Haven Green—busses being dispatched, police car sirens blaring, passerby conversing—cut in.

Last Thursday morning, middle school students from The Foote School and St. Thomas’s Day School joined historians, educators, and Witness Stones Project Founder Dennis Culliton to remember Lucy and Lois Tritton, a mother and daughter who were sold on the New Haven Green on March 8, 1825. The Witness Stones Project is a still-nascent attempt to find and commemorate the lives of enslaved Black people who lived—and often died—in Connecticut. Roughly 70 people attended.

While Connecticut allowed slavery through 1848, Lucy and Lois Tritton marked the final documented sale of enslaved people in New Haven, according to records in the New Haven Museum.

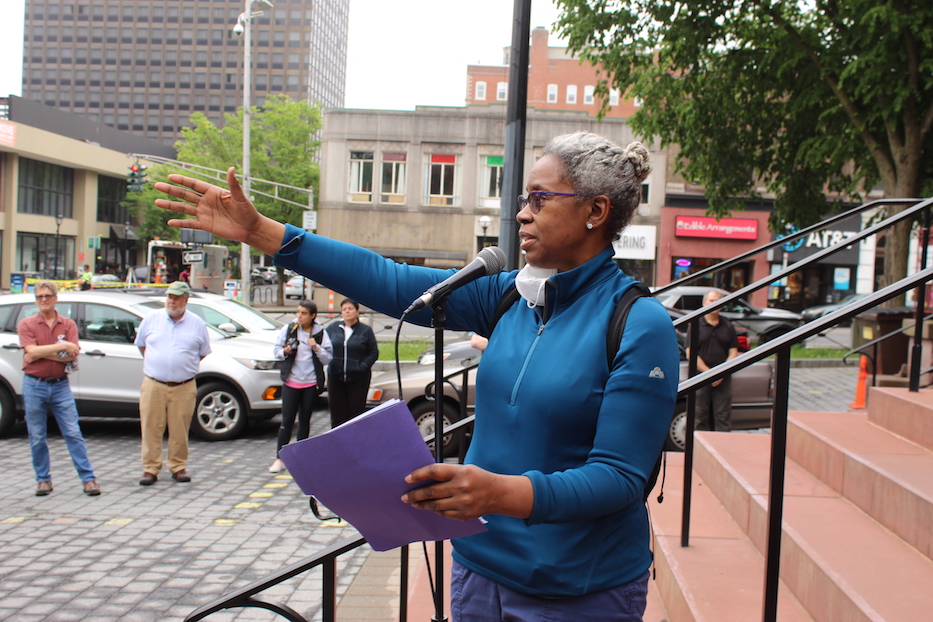

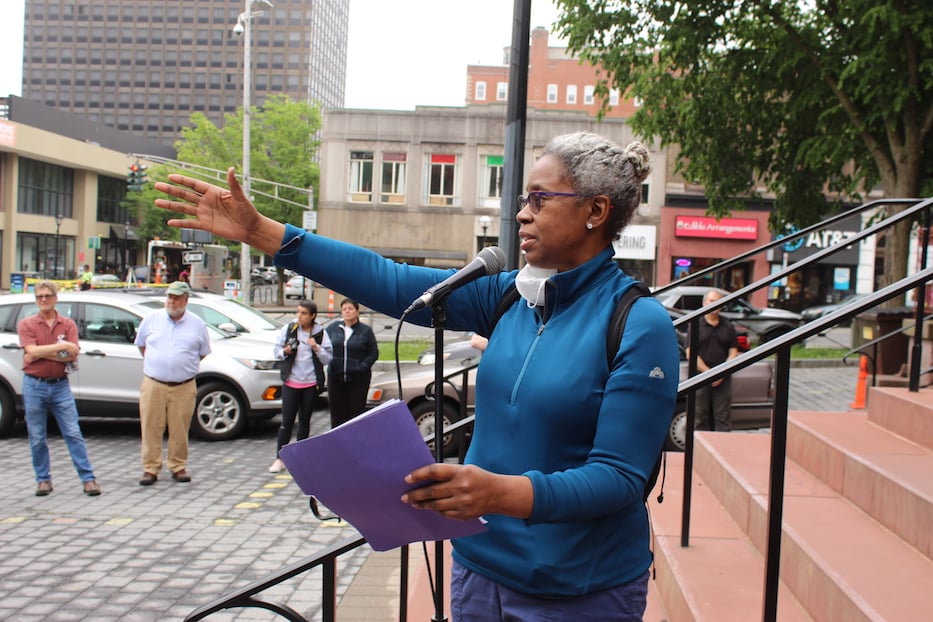

Burns encouraged students to ask: "Who lived here?"

“You’ve all heard of citizen scientists,” said Amistad Committee, Inc. member, public historian and physician’s assistant Joy Burns, describing the process by which everyday people contribute to scientific study.

“But you can also be a citizen historian and do things like dig into your families’ attics and find old pictures and old letters or go to historical societies or historic homes and ask them questions about ‘Who lived here? Where were they buried?’ and ‘What were their stories?’”

A former eighth grade teacher, Culliton founded the Witness Stones Project in 2017 to combat the erasure of enslaved and formerly enslaved people from Connecticut’s history. The Tritton stones are the second to be placed in New Haven; two stones honoring Stepna and Pink Primus arrived at the Pardee Morris House in Lighthouse Point last year.

Top: Students from St. Thomas's Day School sang "Lift Every Voice and Sing." Bottom: Students pore over narrative materials.

The ceremony capped off a multi-week project for Foote School and St. Thomas’s Day School seventh and sixth graders, representing the two schools’ efforts to use project-based learning to engage students more deeply in the history of chattel slavery in Connecticut. The two private schools split the research workload: Foote studied Lois, and St. Thomas studied Lucy. During the process, students cultivated new skills: deciphering several-centuries’ old documents, interpreting Old English, and reaching across time and space to empathize with individuals they’d encountered only through historical documents.

Students used primary sources—original and transcribed—including newspapers, censuses, court records, and city directories. The New Haven Museum and Witness Stones Project team helped compile the research documents. During an hour-long hour-long program, students used song, poetry, and informational speeches to honor and celebrate the lives of Lucy and Lois Tritton.

Lucy was most likely born in West Central Africa in 1764 and later kidnapped and trafficked to the island of St. Thomas, where she was sold into chattel slavery. General R. Tritton, a merchant who sailed ships in and out of New Haven, enslaved Lucy. The enslaving Tritton family was based in Nova Scotia, Canada and owned property in New Haven, where General Tritton’s children attended school for several months a year.

Lucy’s daughter, Lois, was born in Nova Scotia in 1799, and despite laws that prohibited the import of enslaved people into the United States, the Tritton family persisted in enslaving her. In 1825, Lucy and Lois were sold to the abolitionist and Trinity Church member Anthony P. Sanford on the New Haven Green, who emancipated the two of them.

Lois, affectionately known as “Auntie Louis,” was a laundress, a member of Trinity Church, and a mother to her child Henry. She lived to the year 1894, dying at age 95, the second-oldest person in New Haven at the time.

A common theme amongst the students from both schools was the challenge of connecting with Lucy and Lois Tritton when provided with only historical documents—a challenge shared by historians everywhere.

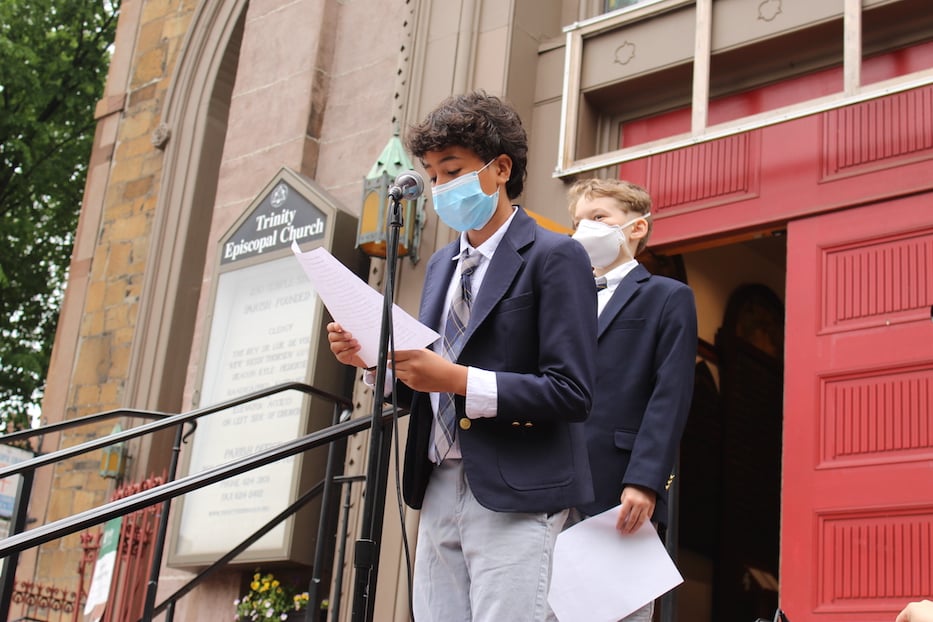

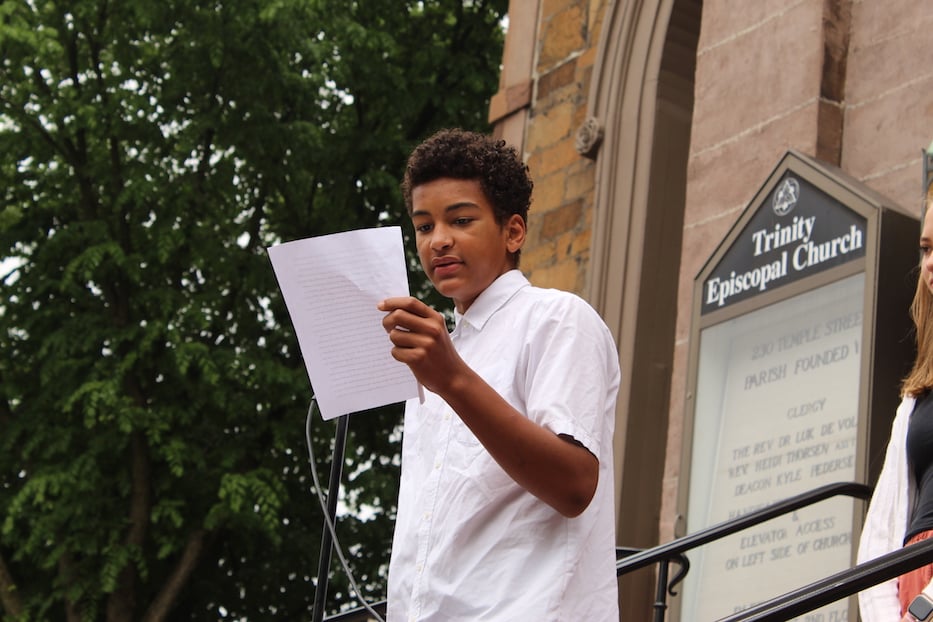

Top: Some of the materials. Bottom: St. Thomas's sixth grader Kaleb Gomez.

In a plaid tie and navy sports coat, St. Thomas's sixth grader Kaleb Gomez mused on the process of getting to know a person. Does it involve “Learning their quirks, flaws, and idiosyncrasies? Learning their likes and dislikes? Or is it something deeper?” he asked.

The end goal, he said, is “to make a person from history a human.”

Dozens of minutes later, Foote seventh grader Kachi Ikekpeazu took the stage to dwell on the same idea: Lois’ enduring humanity. He repeated the words “a human” a total of 10 times to reiterate the message that, in the face of her enslavement as property, Lois Tritton was first and foremost a human being.

Projecting his voice into the microphone, Ikekpeazu declared: “Today, we recognize Lois Tritton as a human.” The audience released a wave of applause.

Daven Kaphar: "Yes, she was a mother. Yes, she was a daughter and, yes, she was slave. But that didn’t define her."

During his reflection on the project, Daven Kaphar let the audience into his evolving thinking about who Lois Tritton was. When asked by their teacher to choose one word to describe Lois, he and his classmates all echoed the word “mother,” Kapahr said. Disappointed that Lois’ life was being reduced into a single word, he went home that night and generated a list of adjectives to reflect what he knew about her

“Lois’ life was way too complex to be described in one word. Yes, she was a mother. Yes, she was a daughter and, yes, she was slave. But that didn’t define her,” said Kaphar.

The students also made interventions into conventional narratives of Connecticut’s participation in slavery as minimal.

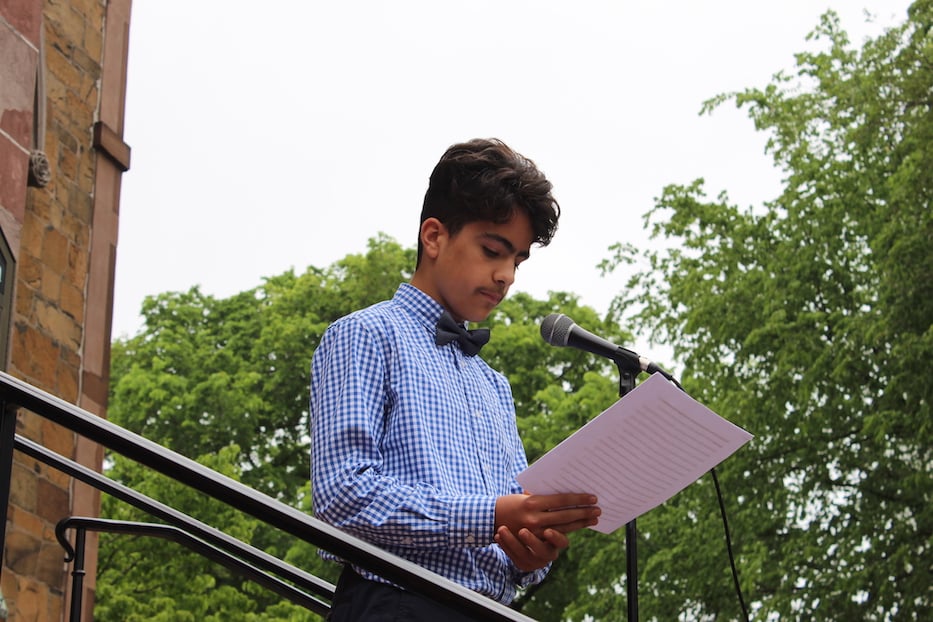

Top: Anushka Gupta. Bottom: Foote seventh grader Poyraz Deniz.

Connecticut was an outlier in New England, said Foote seventh grader Poyraz Deniz. More enslaved people lived in Connecticut than in any other New England state. Contrary to popular belief, living conditions for enslaved people were just as inhumane as were those in the South. And Connecticut was the last state in New England to fully abolish slavery, said Foote seventh grader Gus Witt.

“The reality is, everyone in America, enslaver or not, benefitted from the economic profits of slavery,” Deniz said.

Burns added that the stones will add context to the sparse markers of Black and African history in New Haven’s built environment. Those currently include Ed Hamilton’s Amistad Memorial outside of City Hall, a bronze statue of William Lanson on the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail, and now Witness Stones in Lighthouse Point and downtown.

New Haveners stopped by to read the panels.

She noted that in 1831, New Haven residents voted 700-4 against the establishment of the first ever historically Black college in New Haven, which would have been built in the Long Wharf area.

These markers are too few and far between, she said, calling the student citizen historians to action to add onto New Havens’ history.

“What y’all are doing is you are bringing us a piece of truth today. And it’s our job–the adults’ job–to commit to reconciliation. It’s long overdue and we can’t wait to hear what you have to say.”

To find out more about the Witness Stones Project, visit their website.