Education & Youth | Foote School | Lighthouse Point | Morris Cove | Arts & Culture | New Haven Museum | COVID-19 | Cold Spring School

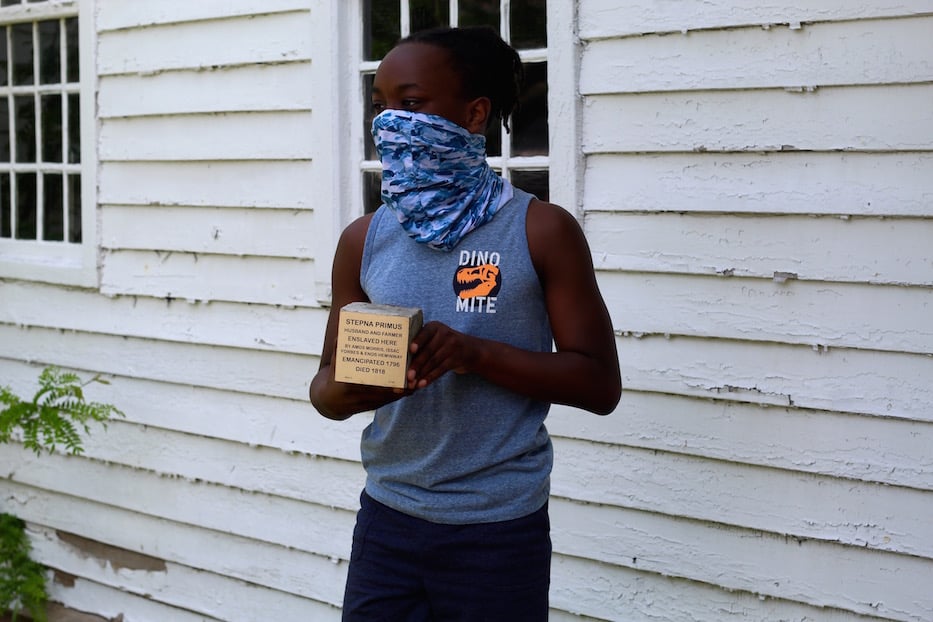

Cold Spring School sixth grader Kymani Chapman. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Sixth grader Kymani Chapman held a heavy cube steady in both hands, the letters on its face glinting. A name caught in the light: Stepna Primus, once enslaved by Amos Morris, Isaac Forbes and Enos Hemmingway in New Haven. Chapman steadied himself, feet spread wide as he lowered the stone into the ground. As he did, over two centuries of untold history came rushing back to a city that has tried to wipe them clean.

Poetry, tribute and song filled the lawn outside the Pardee Morris House Wednesday, as students from Cold Spring and Foote Schools joined the Witness Stones Project and the New Haven Museum to remember and honor Stepna and Pink Primus, a husband and wife who were enslaved at the house during the eighteenth century. During their lifetimes, they were two of 11 known enslaved people at the house. They were emancipated in 1796 and 1800 respectively.

“I thank you on behalf of Pink, and her husband Stepna,” said Ashford State Rep. Patricia Wilson Pheanious, who is the sixth-great-granddaughter of formerly enslaved Guilford residents Montros and Phillis and the descendant of a Black soldier who fought in the Revolutionary War. “This is what the work does. It restores some of their humanity.”

Top: Dennis Culliton, who taught social studies at Adams Middle School in Guilford before starting the Witness Stones Project. Bottom: The newly installed stones.

The Witness Stones Project began in 2017 as the brainchild of Guilford resident Dennis Culliton. A former eighth grade teacher at Adams Middle School, Cuilliton has spent years looking at how primary documents can fill historical gaps that dominant, largely whitewashed narratives are quick to leave out. As the grandchild of Canadian immigrants who came to work in New England’s mills, “I’ve always been interested in the stories that aren’t told,” he said. While living in Guilford, he started to think about the lives that unfolded in the eaves and attics of old Connecticut homes.

What he discovered in town ledgers, church and vital records, census data, property transactions and news bulletins was a story of Connecticut’s intimate relationship with slavery. In New Haven there is a Morris Cove and a Forbes Avenue, for instance, but no mention of the humans these men kept as property. At one point, the state laid claim to the highest number of enslaved people of any of the colonies.

The more he found, the more he wanted to tell its story. The Witness Stones are based on the German Stolpersteine or “Stumbling Stones,” concrete blocks that bear the names of Jews who were taken from their homes to concentration camps during the Second World War. After starting in Guilford, the project has expanded to multiple towns across the state.

“If you do it right, it has a ripple effect in different parts of the state,” Cuilliton said. “Our country hasn’t dealt with truth and reconciliation yet. So if we at least do the truth part, maybe we can get to reconciliation. If we want to cure Connecticut [of racism], we can’t focus on other places. We have to start here.”

Khalil Quotap, director of education and engagement at the New Haven Museum, with Col Spring School students. “It makes me feel proud to be able to tell these stories, along with the other stories we tell at the house,” he said. “We are giving a voice back to these people.”

Wednesday marked the project’s arrival in New Haven. For over a year, both Culliton and New Haven Museum educators have been working virtually with students and teachers at Cold Spring and Foote. He praised Joy Burns, a member of the Yale and Slavery Working Group and the Amistad Committee, for her research into the lives and stories of not only Stepna and Pink, but the other enslaved people who lived in the house, in New Haven, and across the state.

In back-to-back visits to the house, students from both schools arrived to tell those stories. Speaking on Stepna, Cold Spring students Nala Annes and Ava V. noted that one of the cruelties of enslavement is how much it erases from the historical record. They are more certain that consumption ultimately killed Stepna in 1818, for instance, than they are of his early life and the work he was forced to do while enslaved at the house. Charting the history of the Triangle Trade, they estimated that he was stolen from West Africa and brought against his will to Connecticut in the second half of the eighteenth century, possibly the 1770s.

Based on the life and story of Venture Smith, they said that Stepna was likely made to farm or mine salt for Amos Morris, a salt merchant who had a business mining salt out of the Long Island Sound until his supplies were demolished during the Revolutionary War. Morris’ operation relied on filling huge vats with seawater that would then evaporate, and the two guessed that one of Stepna’s tasks may have been lifting huge, heavy pots of seawater. In their research, the two found evidence that Stepna was “rented out,” as if his body were a piece of property.

Top: Ava V. and Nala Annes. Bottom: Livia Doran.

Top: Ava V. and Nala Annes. Bottom: Livia Doran.

There are a few things that remain certain: he and Pink were able to marry each other in a church in May 1791, meaning that there is a record of their union. Together, they had one known child named Chloe. After Hemmingway emancipated him in 1796—perhaps propelled by the Manumissions Act of 1792—he bought land that Pink later owned. He was 50 years old when he died of consumption, leaving his wife and child. Until Wednesday, the museum did not include a record of his or Pink’s existence anywhere in the house.

“We think it’s an important story to tell,” Annes said. “He was more than an enslaved person.”

Later in the day, Foote School students pieced together what they could of Pink’s history, one that they have mapped onto timelines and posters that tell her story in clear, accessible text. In the second half of the century, Morris enslaved Pink through 1800. During that time, “her jobs would likely have consisted of churning butter, cleaning, spinning wool, and taking care of the house,” students wrote.

Initially, Pink lived on and then acquired land and a home through Stepna. But at some point, she lost that land. In 1850—two years after Connecticut formerly abolished slavery, and 23 after the last recorded sale of a human on the New Haven Green—she died in an almshouse. Students said they do not know what became of Chloe.

“We hope that by sharing Pink’s story today, her legacy will live on forever,” said seventh grader Veena Scholand.

Hartford Poet Laureate Frederick-Douglass Knowles II.

Across both presentations speakers personalized the history, from found poetry and original verse to a sweeping tribute from Hartford Poet Laureate Frederick-Douglass Knowles II. In her poem “Open And Unfinished,” Cold Spring student Livia Doran used Amanda Gorman’s “The Hill We Climb” as a template, but imagined it as a way to give Stepna a voice that history erased.

When she read the lines “I imagine heavy weights/heavy weights on my shoulders,” her body bent almost imperceptibly with the words.

An hour later, Knowles unspooled a meditation on Pink’s name, asking listeners what her favorite color might have been (“Was it the color of her stark eyes/Dark as a North Star night?”). Before reading, he thanked students from the Foote School for sharing their research with him. He said he hadn’t known that Connecticut was the largest player in the colonial molasses trade, which used the labor of enslaved people at multiple stages of the process.

“When I walked into the museum today for the very first time, I have to be honest that it was cold,” he said. “Not just cold as in chilly in there, but there’s a chill in the air. When I looked at the timeline of the house and how it was passed down and inherited and so forth, it makes no indication of Pink and Stepna. Or the history of this soil.”

Top: Students from the Foote School. Bottom: Patricia Wilson Pheanious.

Others made the history feel intimate, familial—because for so many people in Connecticut, it still is. Wilson Pheanious was in her 60s when Culliton found her through her father’s obituary. Her father, Lt. Col Bertram Wilson, was a Tuskegee Airman. Through Culliton, she learned the history of Montros and Phillis, which led her to discover that she also had family members who had fought in the Revolutionary War and led very early repatriation efforts.

She is now able to trace 11 generations of her family’s history, including her grandchildren. She said she’s excited for the students to be learning that history early—particularly that “you don’t have to be white to be a patriot.” That knowledge would have helped her decades ago,when she was the only Black girl in a classroom full of white kids.

“When you don’t know your story, you can’t know your true value,” she said. “Finding my family, finding those roots I was disconnected with, had a profound impact on me. It gave me a sense of entitlement and ownership to this country. We were here before America. My ancestors didn’t inherit America. They shaped and fought for my freedom.”

“Real history is our children’s legacy,” she later added. “It is their right and it is their truth. If we do this right, it can also be their power.”

“Millimeter By Millimeter”

Joy Burns (in the salmon-colored cardigan) talking about the project between stone laying ceremonies.

Between stone laying ceremonies, Burns said that the historical research behind the project—and uncovering untold stories of enslaved people in Connecticut—happens “millimeter by millimeter.” When Covid-19 hit last year, many of the archives and libraries on which she relied closed for months.

Last June, as protesters grieved the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd, she got in touch with Culliton and asked him to talk. She pulled in Thomas Thurston and Michelle Zacks from the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition at Yale to see “how do we keep this going despite the uncertainty.” She pivoted to working with Khalil Quotap, director of education and engagement at the New Haven Museum. When libraries reopened, she kept digging.

“When we think of slavery in the South, it’s these run down shacks down the road from the big house,” she said. “In New England, the enslaved people lived in the house because they were valued property. These people lived very intertwined lives.”

She said that one of the reasons there are records—and a history of resistance—is because enslaved people in Connecticut could usually read. Congregationalists believed that both enslaved people and indentured servants should receive and be able to read the Bible.

Once it was possible to read the Bible, Burns said, “you could read the Declaration of Independence. That’s why all of the enslaved people were able to gradually lobby the state legislature for emancipation.”

She added that the work motivates her. When Donald Trump was elected in 2016, “all the white people around me were crestfallen,” she recalled. Already deep in research, she knew that this history had happened before, many times throughout and sometimes in service to American history. She got up and kept going forward.

To find out more about the Witness Stones Project, visit their website.