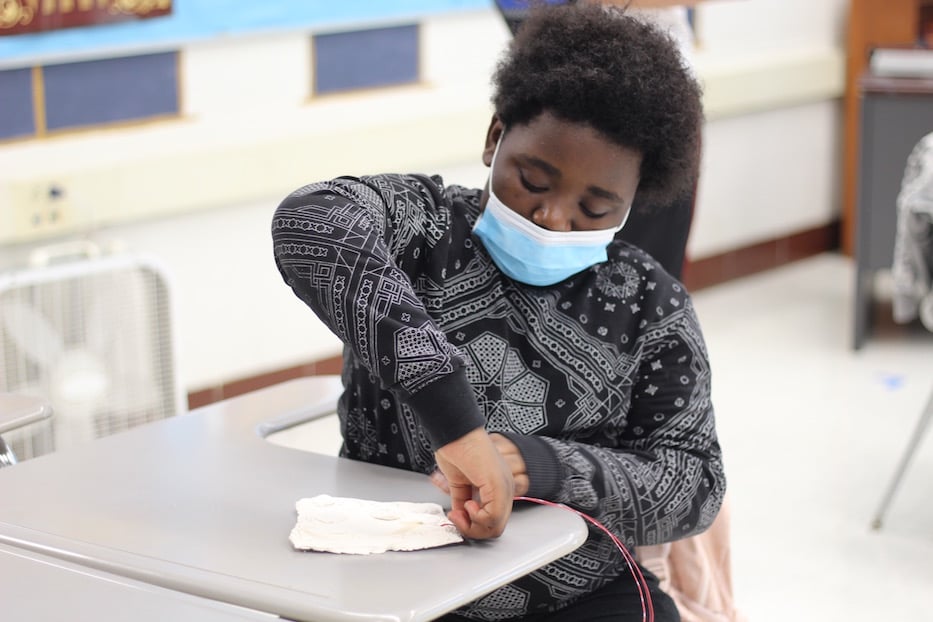

Angel Athumani, who is 11. Lucy Gellman Photos.

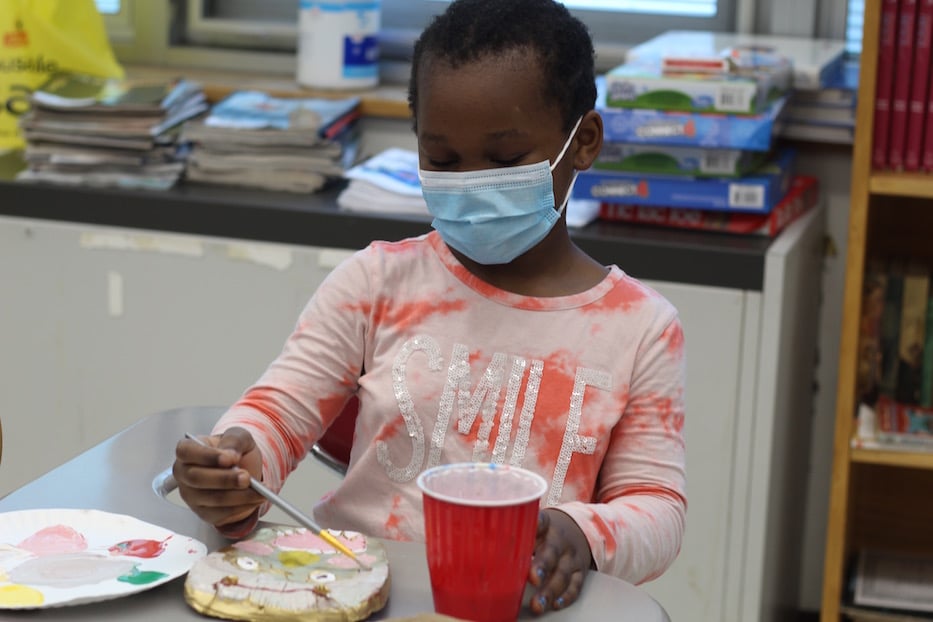

Angel Athumani studied the paint colors carefully, mixing red and white into a marbled pink. Two flushed cheeks appeared above a heart-shaped mouth. She compared oranges and browns against a first coat of gold until she got the hair just right. A likeness to her friend Zawadi bloomed from the clay.

Athumani, who is 11, came to New Haven as a refugee from Tanzania. This year, she is one of 61 students to return to in-person summer education with Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services’ (IRIS) Summer Learning Program. Held at Wilbur Cross High School in the city’s East Rock neighborhood, the program marks the first time since early 2020 that IRIS has been able to welcome students back into a physical classroom.

It seeks to use the arts, alongside academic mentorship, to kick language learning into gear. While just over five dozen students are currently enrolled, roughly 50 show up on a daily basis.

Top: Muzhda Jamal, who came to New Haven from Afghanistan. Bottom: Students work on their masks.

“Getting the summer learning program back in-person is our first step into post-pandemic operations,” said Ann O'Brien, director of community engagement at IRIS. “During the pandemic, we never stopped delivering all of our services. we just changed how we were doing it. Now, we are looking at how we come back and plan for a pretty big increase in refugees.”

At Cross, the school has transformed into a pandemic-proofed celebration of cultures, where medical masks, squirts of hand sanitizer, and temperature checks go hand in hand with sculpture, art making, writing, reading, and music. This year, students hail from Afghanistan, Syria, Guatemala, Ecuador, Haiti, Congo, Tanzania and Sudan, with ages that range from elementary to high school.

In the hallways, students shuffle past each other in hijabs, bright batik prints, and all manner of Frozen and Disney paraphernalia on their way to class. On any given morning, it’s not uncommon to hear a mix of Kiswahili, Pashto, Creole, Arabic, Uzbek, Nuba, and Spanish among other languages as they move from their classrooms to recess outdoors.

Clinard: "Every day, I come home and I’ve learned something about what it means to be human.”

Last Thursday, sculptor Susan Clinard stood at the front of a second-floor classroom, motioning to a row of clay masks that students had sculpted the day before. On the board behind her, a spray of bright magnetic letters peeked out in primary colors, spelling out the word “hola.” A tan poster read “Coexist” with beside the doorway. She raised her hands and the classroom, lively with morning chatter, fell silent.

“Does anybody know why the clay got so hard yesterday?” she asked. Sun streamed in through the windows as if on cue.

Athumani’s hand rose from the back of the classroom. “The sun was coming into the car!” she exclaimed.

Clinard nodded, her eyes crinkling at the edges. Holding up a clay mask that was missing its nose, she explained that sculptures tend to break and warp when the clay is not applied thickly enough in a single place. That’s not a bad thing, she added—she learns from each crack, each unexpected dip, each craggy edge that appears after the firing process. She hopes that students can too.

“Sometimes they break, and that’s okay,” she said. “It happens. It’s part of how art is made.”

As students walked down a flight of stairs to the school’s sun-soaked courtyard, Clinard took an informal survey, asking how many students wanted their sculptures spray painted gold. Every hand went up at once. As she snapped on a respirator mask, summer learning interns and teachers fanned out across the grass, pulling out brightly colored streamers and rods that soon became dancing sticks.

Clinard said she thought of the idea when she realized how cathartic movement could be for herself. Her sister, Wendy Clinard, is a professional dancer in Chicago. She has been known to burst into dance in her studio, swaying among the sculptures.

Soon, students were dancing to Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” with Clinard as they pulled ribbons of color through the humid air. The spray painted masks gleamed in the sunlight as they dried nearby. Seven-year-old Bibi Sadra Zareen Adnan watched the colors flap and fly around her. In 2017, her family arrived in New Haven from Afghanistan. She and her older sister Zahra (Bibi Sadra Zareen Adnan) are in the program; both said they are excited to make art.

Muzhda Jamal, Bibi Sadra Zareen Adnan, and Marya Shikh Issa Alhafez.

Back in the classroom, Clinard watched as students began to paint their masks. Long black eyelashes sprouted across the upper half of one face. A starfish grew powder-blue limbs and a pink smile. Four versions of the Afghan flag appeared across two tables, with thick stripes of black, red and green. Clinard buzzed around the room, answering questions, administering squirts of green and red paint and wiping down messes with clorox wipes.

“I think that without a common language, it’s that tactile expression,” she said. “Every time I do this, I’m blown away. Little stories come out. Students will say, ‘I want to make one for my brother. I want to make one for someone who is in my home country.’ Every day, I come home and I’ve learned something about what it means to be human.”

Around her, students connected over their artworks. Marya Shikh Issa Alhafez, a rising fifth grader at East Rock School, said that she loves the summer learning program, in part because the teachers don’t give homework. Noela Daudi, who moved from Congo last year, showed off a smiling self-portrait, in which her mouth opened to reveal her bright white teeth. Around her, three of her classmates compared notes in Pashto.

Top: Noela Daudi. Bottom: Angel Athumani with her finished mask.

In a corner of the classroom, Athumani filled in a set of brown bangs and dedicated the piece to her friend Zawadi, a 11-year-old Tanzanian refugee who she met five years ago when both of them arrived in the United States. When Athumani came to the U.S., Houston was the family’s first stop. At the time, she was five or six years old and lived in an apartment with multiple families. Zawadi’s family was one of them.

When the Athumani family moved to New Haven, many of their friends stayed in Texas. While the two still talk on the phone as often as they can, Athumani said it isn’t the same. Once painted, the mask made the distance between them feel that much smaller. She held it gingerly between her hands.

The summer learning program comes as IRIS navigates not only a pandemic, but a new presidential administration that raised the cap on refugee admissions in May, only after fierce pressure from refugee resettlement organizations and on-the-ground activists. Three years ago, IRIS started allocating more resources to the crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border in response to a need from the community. Their Spanish-speaking case managers grew from one to three as they began seeing more immigrants and asylum seekers from Central and South America.

While the summer learning program is technically smaller than it’s been for some time—in 2018 it served about 70 kids, and in 2019, closer to 100—the organization has been growing. Demand for its case management and legal services, employment assistance and language training has ballooned in the past year. O’Brien said that employment assistance has seen the highest demand, with applications that can take up to four hours virtually because of a language barrier.

For 16 months, all of those have unfolded online or in limited, outdoor in-person interactions (IRIS’ food pantry remained in person, with Covid-19 precautions in place). As it moves toward more in-person programming, the organization has come close to outgrowing its Nicoll Street space and is in the process of opening a satellite office in Hartford. With a raised cap on arrivals, IRIS is expecting 400 refugees and asylum seekers to arrive in the coming fiscal year, which begins on Oct. 1.

Roughly 250 of those refugees will end up in New Haven. Another 100 will be resettled in Hartford. IRIS plans to work with its regional and statewide partners to resettle the remaining 50.

Both staff members and refugee families are waiting to see how many refugees are able to come from majority-Muslim countries that were barred through Donald Trump’s travel ban. In particular, O’Brien said, IRIS has its eyes on Syria and Sudan. She said that on hard days, IRIS’ success stories keep her going—like the fact that three refugees are headed to the University of Connecticut this year. Or the fact that every one of Clinard’s students went home with a mask.

“This is why we do what we do,” she said.

Learn more about the work Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS) is doing through its website.