CitySeed | Economic Development | Food Justice | Arts & Culture | Food Business | Culinary Arts | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

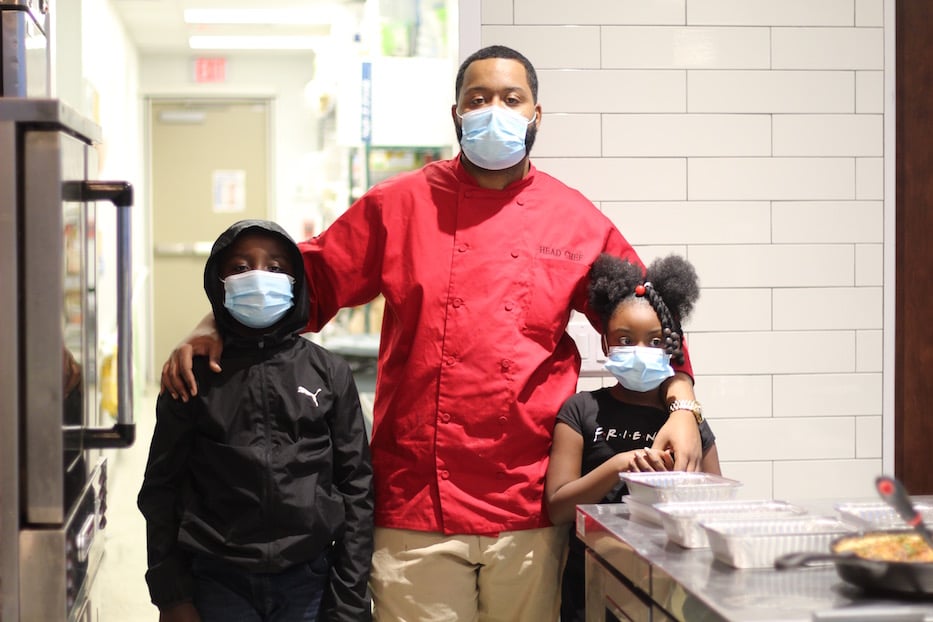

Aaron Lee of Heartfelt Eating. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Aaron Lee paused to see if the macaroni noodles were still whispering with heat, then made his first cut into the cast iron skillet. Beneath a layer of breadcrumbs and deep green parsley, the air bloomed with the sharp scents of cheddar and parmesan. There was a suggestion of garlic, then the nutty hit of truffle oil. Cara Santino took a bite, cheese stretching from the fork, and smiled. It tasted like home, like small comforts, like a Thanksgiving table laid out and ready to say hello.

It’s one of the ways that Santino, the food entrepreneurship program manager at CitySeed, is supporting local chefs, caterers, startups and small food businesses exactly one year into the job. As CitySeed continues to navigate the Covid-19 pandemic, Santino is building out new partnerships, sustaining existing programs, and sourcing suggestions from the community.

Santino began in that role full time in February 2021. For the longtime food justice advocate and founder of Emerge CT’s Restorative Justice Food Program, it is a culinary dream realized.

“My main role is just figuring out what this community of entrepreneurs needs support with, and streamlining it,” they said in a recent interview at Sanctuary Kitchen’s 109 Legion Ave. headquarters, while making truffle mac and cheese with Heartfelt Eating’s Lee. “Making it digestible and accessible.”

Cara Santino in the Legion Avenue kitchen. "My main role is just figuring out what this community of entrepreneurs needs support with, and streamlining it," they said.

At CitySeed, Santino’s work revolves around listening to and supporting early-stage and growing local food businesses and entrepreneurs, who may range from farmers pickling their veggies to refugee chefs building out their businesses. As part of the organization’s eight-person team, they are the sole member of the nascent CitySeed Incubates program, which supports the Food Business Accelerator from CitySeed and Collab and provides businesses with kitchen space and hands-on mentorship.

Following the sale of CitySeed’s 89 Grand Ave. building last year, they are also helping with rentals and use of the commercial kitchen space at 109 Legion Ave., where chefs from Sanctuary Kitchen at CitySeed work during the day.

“I would say Cara's just leveled up our work around food entrepreneurship,” said CitySeed Executive Director Cortney Renton in a recent phone call. “As a chef in the kitchen, she just kind of sees it all and has taken it to a new level. I think most of all, she’s just really built a lot of trust and a lot of respect with our entrepreneurs. You can tell that she cares so, so deeply about each and every one of them. it's been really amazing.”

In the past year, that has translated to work with 56 chefs and local food entrepreneurs, and 14 graduates of the Food Business Accelerator (FBA) program that CitySeed runs with Collab (in the most recent cohort, Renton explained that it’s 14 people across nine ventures). Of those, 66 percent have gone on to legally launch businesses. Renton added that CitySeed Incubates has distributed $5,000 in seed funding in the last year alone.

For Santino, the work never looks the same—in part because every business owner or aspiring chef-entrepreneur has different needs. A given week might include poring over city licensing requirements with one food business, testing recipes with a second, and talking about how to start selling at farmers’ markets with a third (“I get a lot of questions about licensing,” they said, a nod to a labyrinthine, arduous, hard-to-understand citywide process that can become a deterrent for small food businesses). They’ve found particular success with one-on-one advising sessions in which they’re able to work closely with people to fit their individual needs.

In the past year, they’ve led new workshops on menu management, cost control, and pricing among other subjects. With Community Outreach Manager Frankie Douglass, they launched new tutorials on digital marketing, the need for which increased when many businesses were pushed online during the pandemic. As they look ahead, they plan to continue growing that footprint in a way that is responsive to the community.

“I’m grateful that they [CitySeed] gave me the free range,” Santino said. “I want everybody to have access to funds, and to food. I want everybody to be able to feed themselves. I want people to have the same access to resources that rich white guys have … and I just want to make people happy through food.”

For The Love Of Food

Lee and Santino dig in to the mac and cheese (this reporter did too, for the purposes of journalism of course).

That role, which they are still shaping each time they sit down with a chef or budding entrepreneur, has been decades in the making. Born in New Haven and raised in East Haven and North Haven, Santino was "obsessed with food" even as a kid, and became an early devotee of the culinary arts. In middle school, cooking helped get them through their parents’ divorce, during which “everything changed,” and the world shifted beneath their feet.

Food was a whole love language, from lasagna and meatballs to boxed mac and cheese with slices of hot dog mixed in. When they weren’t perfecting a now-signature oatmeal chocolate chip cookie recipe (their friends and family can thank a dog-eared cookbook they picked up at a tag sale) or tinkering with standard dishes, Santino was watching chefs perform alchemy on the Food Network. “I would cook as much as I could,” they said.

During those years, Santino also saw how access to food could be treated as a privilege and a luxury, rather than a basic human right. After once using the last stick of butter in the house to make cookies, they got in a fight with their mom over the need to scrimp and save, rather than waste the precious ingredient on something seemingly frivolous. Years later, the memory still remains in their mind.

It’s a relatable one: many of the city’s would-be or nascent food entrepreneurs struggle to build businesses because they can’t afford the classes, rental and permitting fees, extra time and ingredients they need just to get off the ground.

The pièce de résistance.

As they dipped back into their history, they leaned against the white wall of Sanctuary Kitchen’s Legion Avenue space, their hair haloed in light. Their crisp white mask glowed. They paused for a moment, and then went on.

Santino did not know it yet, but those economic factors were shaping their own career path. After losing their family home to foreclosure in high school, Santino moved in with their grandparents in New Haven and enrolled in liberal arts classes at Gateway Community College, working shifts at a local Boston Market. At some point, they said, a light went off. They were in school to study teaching, but their heart was in the restaurant business. They enrolled at Johnson & Wales University, moved to Providence, and “never looked back.”

In Providence and later Boston, Santino found themselves drawn to jobs that sat at the nexus of food policy, education, management and social justice. In 2012, they became the food program coordinator at Rosie’s Place, founded in the 1970s as the first official women’s shelter in the U.S. It was a job they loved (”at the time, that was the best job that I’d ever had,” they said) and held down while also working in restaurants and cafes across the city, and sometimes back in Providence too. From Rosie’s place, they worked a string of positions across cooking and food justice, including Haley House, Marriott Hotels and Cambridge Public Schools.

Because the hospitality industry pays so poorly, there was never just one job. Santino recalled living in Quincy, Mass. and budgeting over an hour and a half to get to work each day, in a commute that included a bus to the subway to a second bus. By their eighth year of working in the city and its fast-paced schools, cafes and kitchens, “the wear and tear on my body was starting to show,” they said.

Then a friend “dragged me to a grad school fair.” Santino initially balked thinking about the cost of graduate studies. Syracuse University’s Evan Weissman, then an associate professor of food studies and nutrition, convinced them that a degree could be in the cards. He told them about teaching assistantships, which existed for students who needed help with tuition. They went, not knowing it would ultimately lead them back to New Haven.

“I dealt with huge imposter syndrome,” they recalled. They weren’t sure what they were doing among some of the other students, who walked around the campus like they had always belonged there. The second semester they were there, Covid-19 hit, and classes went online. Then Weissman died unexpectedly. Santino knew they wanted to do a project, rather than write a thesis. As they were pushing through to finish, a capstone requirement led them to Emerge CT, where the Restorative Justice Food Program now explores and fights the intersection of food injustice and the carceral system. It also brought them to CitySeed.

“Above And Beyond”

Chef Aaron Lee with his kids Noah, 9, and Aaralyn, 7.

Lee, whose small food business Heartfelt Eating flourished under the Food Business Accelerator from CitySeed and Collab last year, said he is incredibly grateful to Santino and members of the CitySeed team for the guidance they’ve provided. On a recent Thursday, he bounced around the kitchen, his coat a blur of red among the stainless steel surfaces and flickering gas burners. His hands performed a careful culinary ballet, laying cajun seasoning, truffle mousse, and fine shreds of cheddar cheese over bubbly noodles. At just the right moment, he transferred the cast iron skillet from stovetop to oven. Santino made sure it was snuggled safely inside.

What is now second nature was a culinary dream not too long ago. Born in New Haven, Lee lived in New Haven and then Virginia as a kid, then moved back to New Haven as a high school student. At home, his dad was a chef, and Lee grew up in the kitchen watching him cook big breakfasts for himself and Lee’s siblings after working the night shift. It inspired him to start learning to make dishes early, a flair for which he’s only grown since becoming a dad himself twice over.

Nine years ago, he was working in a dishroom at Yale University when his son Noah was born, and he “took that as my opportunity to grow.” From a dishroom, he went on to work in the kitchen at the Yale School of Management, becoming a sous chef in their reopened Whitney Avenue building. “I was just freestyling,” he said. “I would just create things that worked well together.”

He founded Heartfelt Eating in 2017 as a way to give back to the city that raised him. After expanding the business through catering events in New Haven and New York, he became part of the Food Business Accelerator with CitySeed and Collab in 2020, and presented his work in spring 2021. “I’m still growing my flavors as I’m cooking,” he said. “That’s what I’m figuring out.”

In the midst of the pandemic, he has pivoted to grow the business in new ways. When large catering gigs dried up, he found that more people wanted private catering experiences, including in small rental kitchens where they were vacationing. Last August, he was able to leave Yale to pursue the business full time. As he worked carefully over a single, fragrant dish of macaroni and cheese, he made time for the youngest chefs in the room, nine-year-old Noah and seven-year-old Aaralyn.

When he had finished the dish and had a filmmaker take B roll for an Instagram reel, he cut in and doled out small, still-steaming and just-gooey-enough portions out in takeout containers. Santino smiled as they inspected their fork, and took a bite. In between updates on the business, Lee started filling them in on his next big dream of finding a food truck.

“CitySeed has been amazing,” he said. “They really go above and beyond to help.”

To learn more about CitySeed Incubates, visit its website.