Co-Op | Culture & Community | Downtown | Education & Youth | Music | Arts & Culture | Yale Schwarzman Center

Top: Rakhshona Tulkinov. Bottom: Students including Kayla Gomez check out the machines. Lucy Gellman Photos.

High school freshman Rakhshona Tulkinov leaned forward in her chair, listening as the room turned a fiery orange around her. On all sides, conversations fell to a hush. In front of a window that glowed yellow, Ash Fure stepped onto an elevated platform, and began a sonic conjuring. As she lowered a sheet of polycarbonate to a table, the sound clicked and undulated, part electricity and part human.

Tulkinov could feel herself listening with her whole body. She’s played the flute for seven years—but she’d never heard a sound like this.

On a recent Friday, those worlds collided at the Yale Schwarzman Center, as sonic artist Ash Fure opened up her “ANIMAL: A Listening Gym” to band and strings students from Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School. For just over an hour, Fure both performed in and showed students around the gym, a circuit of vibrating rubber cords, interlocking metal bars, sheets of thick polycarbonate, hunks of foam and other sonic machinery designed to create experimental and otherworldly sound.

Like workout equipment, all of the machines operate with human touch—meaning that physical engagement is a necessary part of the process. For Co-Op students, some of whom are just beginning their musical journeys and others of whom are applying to conservatories and taking AP Music Theory, it presented an entirely new way of both listening and understanding sound.

Fure on a recent Friday.

“I think I consider that space as an invitation into a certain kind of relationship with one's body and [with] full listening, awakeness, and connection,” Fure said Friday afternoon, following the visit. “You’re not following a story. You’re invited into pretty vulnerable grounding positions, and it does something to the collective nervous system.”

From the moment Fure welcomed Co-Op students into the space, their bodies still waking up in the gray morning, that approach was on full display. Seated on a foam-padded, overturned milk crate—her seat of choice for the installation—Fure looked around, taking in the five dozen soft, curious faces that stared back.

“Does anybody know … can anybody tell me what sound is?” Fure asked.

“It’s a vibration,” ventured Miles Sclafani, a freshman at the school who is studying the drums with teachers Patrick Smith and Matthew Chasen. Sclafani, who got into music through his dad, went on to describe sound waves, his voice steady as if to show a wave in real time. Fure nodded, listening carefully to the contours of each word.

“Yeah,” she said. “So it’s a wave, it’s a vibration. Does anybody know which vibrations the ear tends to hear?” There was a beat, then Tulkinov and Sclafani raised their hands. When they spoke, they were so quiet that Fure leaned in to listen. In the intervening silences, it seemed that every body in the room was more attuned to the tiny bones in their inner ears than they ever had been.

“So, sound moves in pressure waves,” Fure said, as her voice traveled out to the ears across the room. “Basically, there’s a vibrating source that bumps a bunch of molecules, and if you’re near enough to that … you hear it.”

She motioned to an installation to her right. From a black rubber mat on the floor, a chrome-colored machine rose to well over six feet, parts fitted neatly together and suspended by thick rubber cables. Behind it, two long black rectangles tilted upwards, toward the dome’s oculus. At a quick glance, it looked like a piece of gym equipment, just waiting for someone in basketball shorts and a sweat-stained t-shirt to take a turn.

Instead, Fure explained, it was there to help people hear and visualize sound differently. Beside her, Tulkinov and Sclafani came forward to test out the equipment. As the machine turned on, a percussive, almost industrial rattling filled the room, as if someone had jumpstarted an assembly line in the middle of an Ivy League university. Fure lifted and lowered a long, solid black sheet, urging the room to listen closely without ever having to use the words.

“We’re really trying to build on our ability to hear one another,” she said before moving across the room with another call for volunteers. From a second machine, a network of black rubber cords dangled above the floor, as if they belonged to some weight lifting device from the future. This time, the machine came on with a meditative hum, the vibrations mimicking pressure and sound on a cello string.

Yaki Francisco.

As if on cue, Lugo, who had been standing near the back of the room, stepped forward to watch. Now in his second year teaching strings at Co-Op, he’s been working to build back the school’s orchestra since last year. He’s also a working musician himself, with a deep love and decades of experience on the double bass. As a Co-Op student slipped the rubber cables carefully over her neck and shoulders, he watched the sound travel through the device, and make its way across the room.

A few whispers and giggles floated through the room; students were now sufficiently interested. The next time Fure called for volunteers, half a dozen hands went up. Jaden Cuapio, a junior studying the violin, beamed as Fure called on her. As she made her way across the circular room, she eyed her destination: a metal contraption that rose toward the ceiling, with cylinder-shaped speakers hanging down from its four sides.

Slowly, Cuapio took two black cylinders, and pressed them to her ears. The sound closed in around her. As fellow students did the same, some did a double take; others leaned forward and moved from side to side, as if the sound had knocked them temporarily out of space and time. Fure stood at attention, back straight and legs shoulder-length apart, as she moved the cylinders around her head.

For Fure, that ability to think and listen differently is part of the hope. “It’s so hard to be alive and in our bodies together and waking up to the intensity of this moment,” she said in an interview afterwards. “It’s a pretty simple invitation and I think the sonic energy … it’s sort of there to activate a somatic experience and to kind of shape time.”

She added that there’s something about collective listening that helped birth the installation. During her time in quarantine—when many of Co-Op’s current students were still in middle school, and struggling to move through remote classes—Fure began to think about sound differently, wondering how she could warp, alter, and play with it in a small and enclosed space like a home with a laptop.

It was the early days of Covid-19, and Zoom was turning the world completely upside down for musicians and other performing artists. “All of your artistic experiences were getting compressed,” she remembered. So she started experimenting—first just with what she had at home (pint glasses, for instance), and later during a 2022 residency at the Schwarzman Center. The life-sized gym pieces come from stock-a-studio, which brought Fure’s vision to life.

Nowhere was her interest clearer, perhaps, than in an excerpt from “ANIMAL” itself, which she will be recording in L.A. this month. As Fure stepped up onto a slightly elevated stage, lights fading around her, she became bird-like, rotating a sheet of polycarbonate over a platform fitted with two bowl-like apparatuses. As it glowed with a butter-yellow light, the vibrations sent a hammering pulse through the room, tempered to a whirr when Fure lifted the sheet. In the low light, it became a mirror, beaming Fure’s reflection back in shades of yellow and clementine.

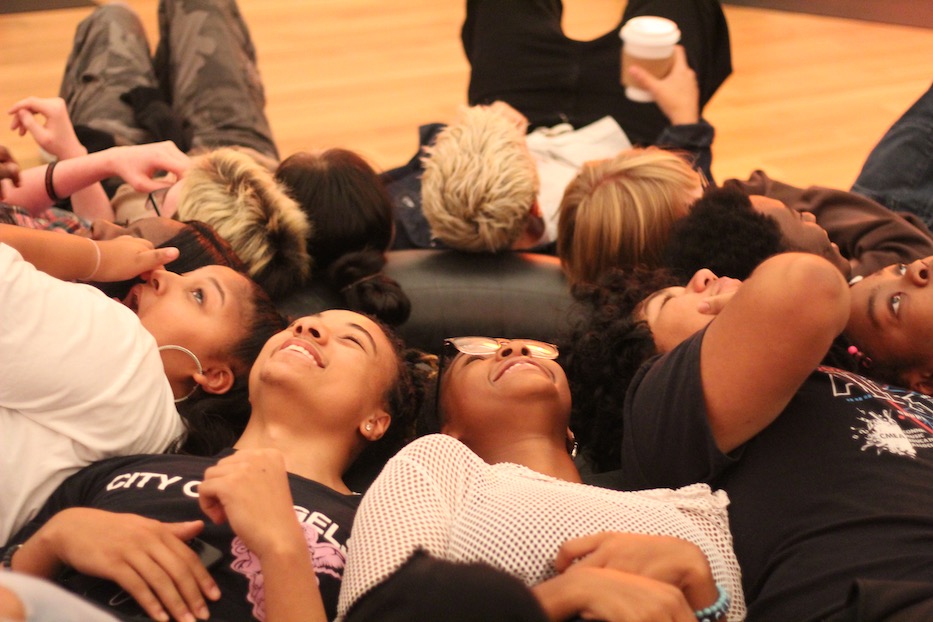

After the burst of applause that followed, Fure encouraged students to explore the gym, watching as they dispersed to different corners of the room. On one side of the dome, a small line formed beside a wind tunnel that could have passed for a bench press. Other students rested their heads on a rubber donut in the middle of the room, backs to the floor as they giggled at the sound, and looked up to where the dome’s oculus met the clearing sky above.

Beside it, Tulkinov took her turn at a seated sonic machine fitted with metal balls that rolled loudly across the top. At the humming, cello-like device nearby, Yaki Francisco leaned in, letting a length of rubber vibrate over her arms and shoulders. A junior at the school, Francisco started playing the cello years ago, but said she’d never thought that sound could do what Fure asked it to.

“It’s not something you usually hear,” she said. “It makes you think, ‘Oh my God, there’s so much more to music than I realized.’”

As she took her last walk around the space, junior Kayla Gomez agreed. Her freshman year, she picked out the viola, which she thinks of as “the middle voice in the orchestra,” for its sweet and tempered sound. Friday opened her eyes and her ears, she said: she left the dome thinking about “how music can be made in different ways.”

Outside the dome, Smith made sure all of his students were present and accounted for before heading out. Back inside, Fure waved goodbye to the last stragglers as the room again fell silent. She would perform again, filling it all the way with sound, in just a few hours.

“Oh, I loved it, I loved it,” Smith said. It’s vital, he added, “for them [students] to have a visceral experience that connects them to the sound.”