Co-Op High School | Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | Community Heroes

Patrick Smith, who has taught at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School since 1998. Pictured in the background is student Paris Bland. Lucy Gellman Photos.

A champion of music education has made the shortlist for one of the highest artistic recognitions in the country. He’s celebrating by doing what he’s done for a quarter of a century—walking into his College Street classroom, greeting dozens of young musicians, and striking up the band.

That teacher is Patrick Smith, the music department lead teacher at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School (Co-Op). Last week, he was named a semifinalist for the 2023 Music Educator Award by the Recording Academy and Grammy Museum. Since 1998, Smith has taught at Co-Op. Now, he is among 25 semifinalists from across the country, out of an original pool of over 1,205 nominees.

The semifinalists hail from 25 different cities across 18 states. Connecticut has a second finalist in Torrington High School music teacher Wayne Splettstoeszer.

Since arriving at the school, Smith has transformed the lives of hundreds of students, from Latin Grammy winners and Netflix executives to aspiring music educators, producers, and college students who credit him for getting them there. It will mark the second Grammy recognition for the school: Co-Op snagged an award for community engagement from the recording academy in 2017.

Smith on Monday, with his first period jazz band. The ensemble comprises juniors and seniors at the school. Senior Diana Perez (in yellow sweater) said that the stories Smith tells have helped her in not only her musical and curricular practice, but in life.

In addition to his work in the classroom, Smith is an accomplished professional musician and martial artist, and is trained in Kingian Nonviolence. Locally, he has done work with the anti-violence group Ice The Beef, which works to stem the spread of gun violence among youth in New Haven.

“I’m flattered, you know?” he said Monday, between sections of a junior-senior jazz band and a tight-knit percussion ensemble. “More than anything, I’m glad I’m having a positive impact on the kids.”

“For me and many others, he became a father figure, or a second father figure,” said Marcos Sánchez, a 2001 Co-Op alum who went on to become a professional artist and in 2018 won a Latin Grammy with Smith cheering him on from the audience. “’I'll be 39 next week, and I still call Smith all the time. He's always there for me. For him, music is about humanity.”

While Smith arrived at Co-Op in the late 1990s, his road to music education goes back decades to Washington State, where he was born and raised outside of Seattle in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. Music was perhaps in his DNA: Smith’s mother was a trained concert pianist, and his father played by ear. During a childhood that could sometimes seem tumultuous—he didn’t see his dad much, and “we bounced around a lot”—music became a constant.

He credits his mother, June Lee Smith, with those beginnings, he said Monday. As a young kid, he saw a teenager playing Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Flight of the Bumblebee” on xylophone during the Ted Mack Amateur Hour, and knew at that moment what he wanted to do. His mother found a xylophone teacher and secondhand marimba on which he could start. The instrument—on which he still plays—was $60, a fraction of what it would cost today.

By fourth grade, Smith had formed a band with fellow students, playing covers of Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass alongside flute, keys and drums. A few years after that, he began traveling with members of the Crossroads Quartet, four gospel singers who packed a keyboard and electric bass into their bus, and made stops from the West Coast to the Midwest. By high school, he was playing with Bellevue Philharmonic, which shut down in 2011, and subbing with the Seattle Symphony.

Even as his musical star was rising—most notably playing music with the Rolling Stones in the late 1970s—he faced adversity at home. When his mother became unwell during his last three years of high school, Smith “bounced around King County,” living on the street, in cardboard boxes, and later in the homes of families and fellow musicians who took him in. He jumped between three different high schools, continuing to study music outside of the classroom. He credited Robin Myers, then the principal tympanist at the Bellevue Philharmonic and a classical DJ at Seattle station KING-FM, for looking after him for a year when he was 15.

When he applied to college, it was to study music education, a suggestion of his mother’s that he took to heart.

Students Alanis Rios and Samaia Brantley in Smith's percussion ensemble.

It seemed that others could see the teacher in him before he could see it himself. Even as a freshman at Western Washington University, Smith was teaching percussion pedagogy to his peers and older students, a position he held for three years. Outside of school, he played professionally with the Seattle Symphony and freelanced where he could, landing gigs that ultimately included music for the the Rolling Stones, Paul Cetera, and Aretha Franklin. After realizing that all of the percussionists he looked up to had studied with musician Fred Hinger, who was on the East Coast, he applied to train with him at the Yale School of Music.

“Yale was my only shot,” he recalled Monday. After the program accepted him, he moved to New Haven to study, then took a gap year as the principal percussionist with the Hong Kong Philharmonic before finishing graduate school. He expanded his percussive footprint, becoming a member of the New Haven Symphony Orchestra (NHSO) and Orchestra New England (ONE), both of which he is still active in today. For the last eight years, he has also helmed ONE’s education committee.

Smith never planned on settling down, he said in an interview for the 41st annual Arts Awards last year. But when he met his wife, the percussionist and educator Melinda Alcosser, “I realized I had to change my life.” By his own description, he “dusted off” the degree in music education, and started applying for jobs. He became an adoring father twice over, to daughters Lucy and Jody Smith (the family also has two fur babies, named Santana and Ike).

Before arriving at Co-Op in 1998, he served as assistant director of bands at Yale, then taught at North Haven Middle School for three years. Even then, Co-Op was always in the background: he recalled early conversations with educators Keith Cunningham and Charles Warner, Sr. about the arts school as they were working to get it off the ground.

Then in late 1998, he arrived at Co-Op, when the school was still in a building on Dixwell Avenue (the move to 444 Orange St. came in 1991; the move to College Street in 2009). When he entered the classroom, the band was just five students. They included Sánchez and Pega Visão Salvador Club Founder Aaron Mitchell, a former Netflix executive whose musical foundations continue to influence him today.

Working with choral director Harriett Alfred, he grew that five-member group to a 65-piece wind ensemble, two 25-piece jazz bands, a 100-voice choir, and a 45-piece orchestra. In a phone call Friday, Alfred said she’s grateful for such a collaborative colleague, which has been true since the minute he arrived at the school over two decades ago. The two have become inseparable: they are sometimes mentioned as a unit (just try saying “MrSmithMsAlfred” 10 times) and now run an advisory together.

That collaboration has continued during the past three academic years, as students have transitioned from in-person to remote learning to hybrid and back to in-person. During the first months of the pandemic, Smith braved the online pivot with new technology, teaching himself, students, and staff how to use mixing and video software to keep playing apart, together. In lockstep with Alfred, he worked to keep students engaged despite the distance.

When they returned last year, he found that many had struggled to keep up. Because the district runs on a lottery system, he added, he never knows exactly what the band will look like. This year, it has him picking up a bass during jazz band, because no new students had the instruments in their wheelhouse. His percussion students will be backing Alfred’s choir during “Betelehemu,” a Nigerian hymn that they will perform at the winter concert.

“The pandemic killed us,” he said, although he does not tend to dwell on what’s been ostensibly lost. Now, “We’re building back.”

“He Let Us Be Us”

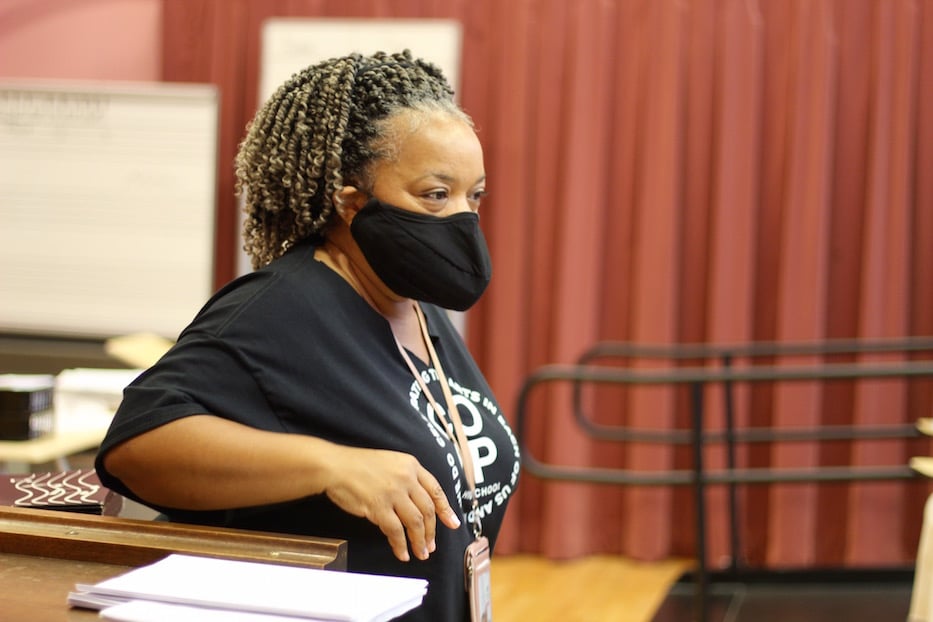

Harriett Alfred, who has worked with Smith since 1998, pictured in September 2021. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

As news of Smith’s semifinalist position spread last week, fellow staff and alumni alike reacted with excitement, pointing to the honor as both well-deserved and long overdue. While Smith’s work has garnered recognition in the past, including with the Duke Ellington Fellowship from Yale and the Mary Hunter Wolf Award at Co-Op, this may be the most high-profile national honor he has received.

Alfred called their relationship “a yin and yang situation.” Smith knows how to keep his cool “when things get a little hairy,” she said. In return, she’s detail-oriented, calm in the face of mountains of paperwork and clerical minutiae.

In over 20 years working together, “we have learned how to choose our battles wisely, and we have seen a lot of things in the district change, and we have learned to be flexible and just be ready come what may,” she said. “But we have also learned to speak [up] when necessary on things that need to be addressed.”

They have also kept each other level-headed, from collaborative concerts and “several in-depth spiritual talks” to online programming during the pandemic, she said.

During the first months of Covid-19, it was Smith who often helped Alfred push through the isolation of online learning and quarantine. If she gets her way, she said with a smile in her voice, they will retire at the same time, and leave the building dancing. With a laugh, she said it would be the professional equivalent of Heathcliff and Clair Huxtable dancing “right off the stage.” She can't imagine a classier and more fitting exit, she said.

“Talking about Pat is easy, because I love the dude,” she said, before heading to a church choir rehearsal last Friday. “That's my boy.”

The musician and producer Marcos Sánchez talking to students at Co-Op in October 2020.

In conversations with former students, he was often simply “Smith,” a nickname that has withstood two decades and three moves. In a phone call last Friday morning, Sánchez recalled the impact Smith had on his then-nascent career, from late-night rides home to in-school production projects where he got a taste for the recording work he now does for a living.

Growing up on Congress Avenue—Alfred was actually his teacher at Truman school before she came to Co-Op—Sánchez saw firsthand how some teachers shrugged him off as another kid from the Hill who wouldn’t go very far.

Smith was never that person, he said. During his time at Co-Op, band students recorded an album every year, each of them tasked with a track. It became an exercise in group work and problem solving, Sánchez said. Smith would wait for students to finish their work after school, sometimes staying as late as nine or ten at night before driving them home in his blue Subaru.

Smith drove them to masterclasses and concerts across the state, including one at Western Connecticut State University that “changed my life as a musician,” Sánchez said. He didn’t scoff or second guess a student based on where they lived or how they showed up to class: he just gave them the space to play. When Sánchez runs into a musical snag even now, “I always go back to that basement at Co-Op, to that music room,” he said.

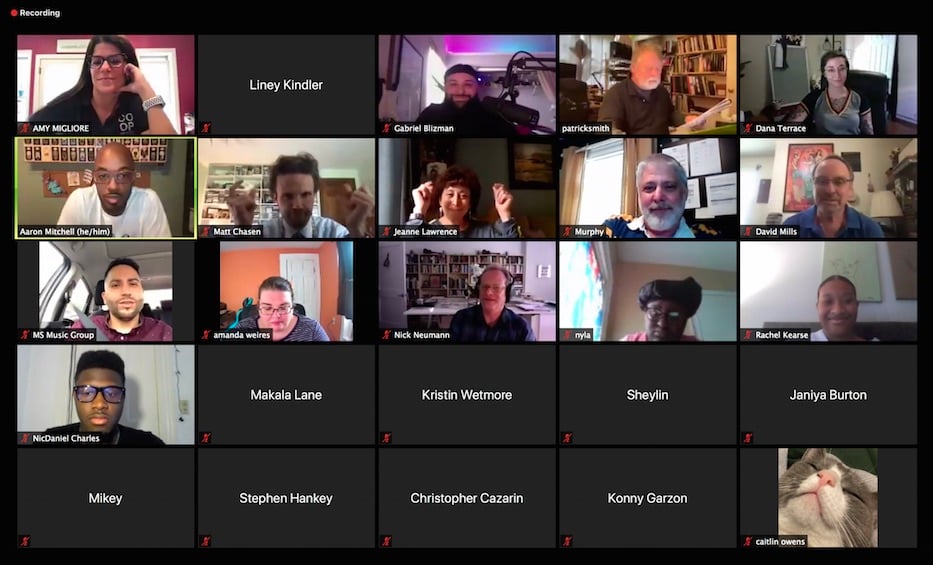

Alumni and students meet on a virtual panel in June 2021. Screenshot via Zoom.

He’s not the only one. Aaron Mitchell, who graduated in 2000, remembered meeting Smith his junior year of high school. Mitchell didn’t take to Smith immediately, he said: he seemed too unstructured, with a belief in letting students experiment that wasn’t exactly Mitchell’s speed. Smith gave him space until he came around. He ultimately helped Mitchell get his first saxophone through the Hamden-based nonprofit Horns for Kids.

“He meets everybody where they are,” Mitchell said in a phone call Friday morning from his home in Los Angeles. “He treated us all as individuals. He let us be us. He gave me my distance and he let me sulk in the corner” until Mitchell was ready to dig into the music.

“I didn't see myself as having a personality that was worthy of merit, and he kept seeing something in me,” he added. Like Sánchez, Mitchell grew up in the Hill in the 1980s and 90s, during a time now remembered for violent crime and a crack epidemic that ravaged the city. For years, “I remember having teachers who said, ‘I don't know why I bother with you kids, you're gonna end up dead or in jail.’”

Then there was Smith, who saw his students’ humanity on full display. After Mitchell graduated, the two stayed in close contact; Smith was one of his entry points into the Yoruba culture and history on which he is now building the Pega Visão Salvador Club. If New Haven was, by and large, “an environment that was telling us that we did not deserve to succeed,” Smith was an exception.

“He saw himself in all of us,” Mitchell said. “Not in an 'I'm an ally’ kind of way. He never felt like the guy from Guilford who swooped in to teach the poor Black kids ... he just wanted to make a connection. It was just really about being a really amazing human being.”

That feeling of deep, often effusive gratitude echoed among younger alumni. Stephen “Gritz” King, who has continued to make music as a solo artist and a member of the band Phat A$tronaut, praised Smith for pushing him when he got to Co-Op in 2006. After years as “musically a big fish in a little pond” in elementary and middle school, King arrived at the school and realized that he hadn’t been taking his practice as seriously as he could.

“He [Smith] was never one of those guys who was like a drill sergeant, he made it fun,” King said in a phone call Monday afternoon. When students stepped into Smith’s classroom, they learned about more than music: Smith brought in stories from his life, and from his time learning martial arts to lessons he picked up from professional music work.

King playing at The State House in 2019. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

King remembered one such story, in which Smith encouraged students to use the principles of Qigong to be more aware of the way energy flowed through and from their hands. When in 2009, King was part of a student band called Urban Love that played during lunch, Smith cheered them on.

During King’s senior year, Smith helped him prepare for an audition that got him into the music department at Western Connecticut State University, where he switched majors, but continued to play. His belief in education—and educators—ultimately brought him back to the school. He is now the outreach and engagement coordinator for Co-Op After School (CAS).

He said he counts Smith among his favorite educators, a list that also includes Alfred and Co-Op drama teacher Robert “Espo” Esposito. “Even now, you know, I look at him like an uncle,” he said. “He's always been that way.”

“I think he is a great example of what teachers, educators, instructors need to be,” he added. “I want my children to meet Mr. Smith.”

And The Band Played On

Members of the jazz band.

In Classroom 215 Monday morning, that tenderness was on full display as students slipped into first period jazz band, and started the day with a run-through of “Happy Birthday.” In the second row, senior MacHenry Charles rested his saxophone on his lap and looked around at his classmates. The clip was for his brother Nicdaniel, a 2021 Co-Op grad who is now studying music education and vocal performance at the University of Hartford.

The class was ready to record, he and fellow students agreed. At the front of the room, a bass hung on Smith’s front, so natural it seemed like an appendage that had been there, unnoticed, for years. On the count of three, vocals entered the fray, horns following on their heels. In the trumpet section, Caleb Nierenberg lifted his horn in a Ghostbusters uniform, a reminder that even high school students celebrate Halloween.

The morning was just getting started—although by then, Smith had been there for hours. Before school starts, he’s often there to work one-on-one with students who request extra help and individualized attention. From their warm up scales (he uses a "light to dark" chromatic framing, which he demoed in a video for the Grammy audition) he directed the group to “Take Five,” which it is rehearsing for a Dec. 20 winter concert.

On percussion, DeMarcus Nixon laid down a carpet of drums and cymbal, a low, swishing sound working its way through the room. When trumpet wove through the front rows, sax responded with a full-bellied wail. Flute and keys jumped in, rising to meet the sound of brass and woodwind. Beside Charles, band instructor Matt Chasen helped lead the group on sax. To a solo, horns and flute responded with quick, high-pitched bursts of sound.

In the front row, senior Diana Perez watched every movement of Smith’s hands, listening as Chasen counted musicians out from behind her. A flutist who has been studying the instrument since the sixth grade, she said she likes being in band with Smith, because she learns from the stories he tells the class. He often talks about his undertaking of both music and the martial arts as a reminder to students to practice, she said.

“I apply that not only to my studies at Co-Op, but to life,” she said.

Back at the front of the classroom, Smith started handing out copies of Victor Lopez’ “Burritos To Go,” joking that this year’s winter concert has taken on a culinary theme (the set also includes Kris Berg’s “Tastes Like Chicken”). After listening to the group play it through once, he directed his attention to Alanis Rios, a junior who picked up the saxophone earlier this year.

Senior MacHenry Charles. After picking up the sax two years ago for the first time, he said he wants to continue it in college. He hopes to attend Howard University next year. Lucy Gellman Photos.

When she came into the class this year, Rios had been playing the bassoon for seven years. But Smith needed another sax player. "He saw my potential," she said.

“Let me hear you again,” he said. The room was quiet as Rios leaned in, and a steady, low sound unfurled from the bell-shaped mouth of her instrument.

“Put a smile on that,” Smith said. It lifted the note, as if the movement of Rios’ mouth had pulled the measure up off the ground. When she did, he nodded approvingly.

He turned to the end of the song, walking over to the white board toward the door of the classroom. Drawing an f with curled edges—the forte sound—he told the group that they were going to go for volume. When the classroom exploded in sound, he listened, then rewound the clock. He looked at the trumpets warily.

“You’re so late it’s tomorrow!” he said. The comment was gentle at the edges; students smiled as it reached them, and they stood to run the last bars over again. There were just over six weeks left until the concert, and they had work to do.

Smith checked the clock, then lifted his hands to cue them in.

To watch more of Smith's jazz ensemble, click on the above videos.