Co-Op High School | Downtown | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | Education

Jaiden Shoulders, who gigs outside of school as a church musician, with fellow senior Caleb Davis. In addition to piano and drums, he plays trumpet and trombone. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Patrick Smith raised his hands, tapped one foot, and scanned 17 pairs of eyes staring back at him. At the piano, Jaiden Shoulders eased into a rhythm that bounced under his fingertips. Drums wove their way between the keys. A trumpet warbled, and then bellowed to life from the back row. As three saxophones joined in with a squeal, flute trilled its way in.

The band was back. For the first time in 16 months, there wasn’t a screen in sight.

Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School (Co-Op) exploded with joyful noise Monday morning, as the school’s 576 students masked up and returned to their classrooms after a year and a half of remote and hybrid school. For some, it is the first time that they have been in the school building—or in a high school at all—since March 2020.

There are currently 162 freshmen, 160 sophomores, 132 juniors, and 122 seniors studying dance, drama, creative writing, visual arts, and musical performance at the school. Arts Director Amy Migliore confirmed that there is also a waitlist for the school.

Seniors Karla Campos (in foreground) and Brandon Carrera.

“It doesn’t feel real,” said clarinetist Karla Campos, a senior who finished both her sophomore and junior years online. “I woke up this morning. I went to the bus stop. I came through the doors. It feels like I never left.”

The school, which graduated 135 seniors last June and held summer and orientation programs for freshmen this year, was ready for her as she walked through those doors. Hallways sat decorated with stickers for social distancing, with arrows marking lanes for foot traffic and reminders to properly mask up. Student art covered all four floors of the building, from still life photographs to multimedia sculpture. A pair of narrowed eyes printed on vinyl waited for students who made it up to the fourth floor.

As students picked up their blue schedules and made last-minute dashes to their classrooms, it seemed that no one used the word “behind.” Hallways filled with one-armed hugs and elbow bumps. Students rocked curly fades, electrifying blue hair, long box braids and platform boots with bedazzled and polka dotted masks. Drama teachers waved open-handed hellos from outside the auditorium. A photography class on the first floor exploded in laughter that floated out into the hallway.

A Choir Returns

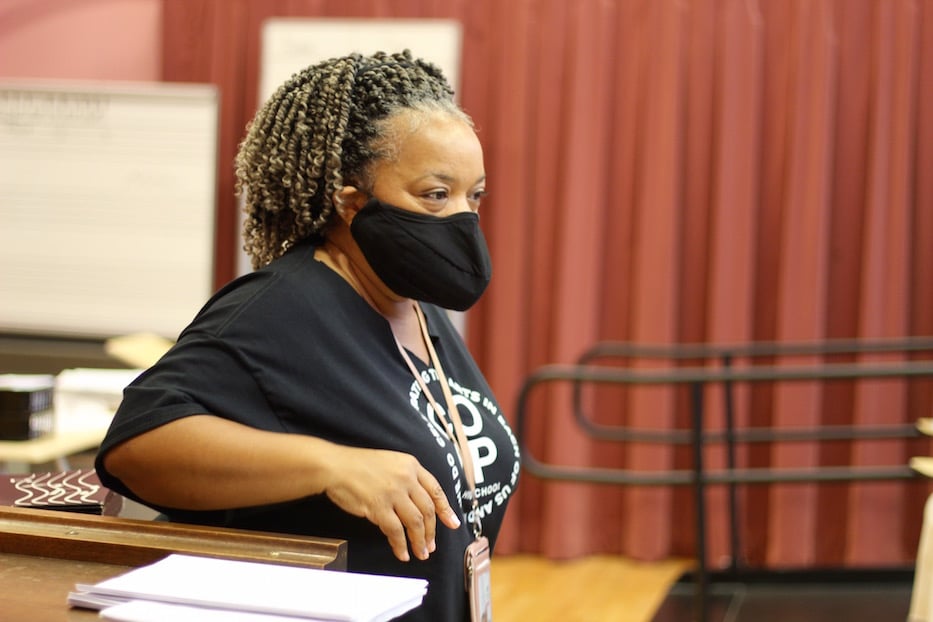

Choral director Harriett Alfred in a singing mask. Students may be using a second plastic mask that catches droplets in a compartment later this year.

Just minutes before 9 a.m. almost two dozen sophomores found their way into Harriett Alfred’s choir class. Ebullient, sometimes sing-song cries of “Hi Ms. A!” christened the space. A few students exchanged high fives and grasped hands. Others ogled the pile of new fabric singing masks heaped on the piano like a pile of oversized fabric duck bills.

At her desk, Alfred checked students in, taking attendance and welcoming new faces. Every so often, she recognized a student who had been on screen and greeted them with delight. A video played over her desk, winding back the clock to sometime before March 2020. In it, Co-Op students swayed in long robes, their faces unmasked as they belted from the stage. This year, Alfred explained, it was going to look different—but students would still get to sing together.

Even before Alfred walked to the front of the room, an energy hummed among the desks. Friends caught up after months on Facetime, exchanging notes on summer jobs and answering gospel trivia as Alfred tossed it into the room as she pored over schedules. In the front row, Hayden Earnshaw sat with a bright, glittering lizard on their desk, as if it too was anticipating the start of a cacophonous year.

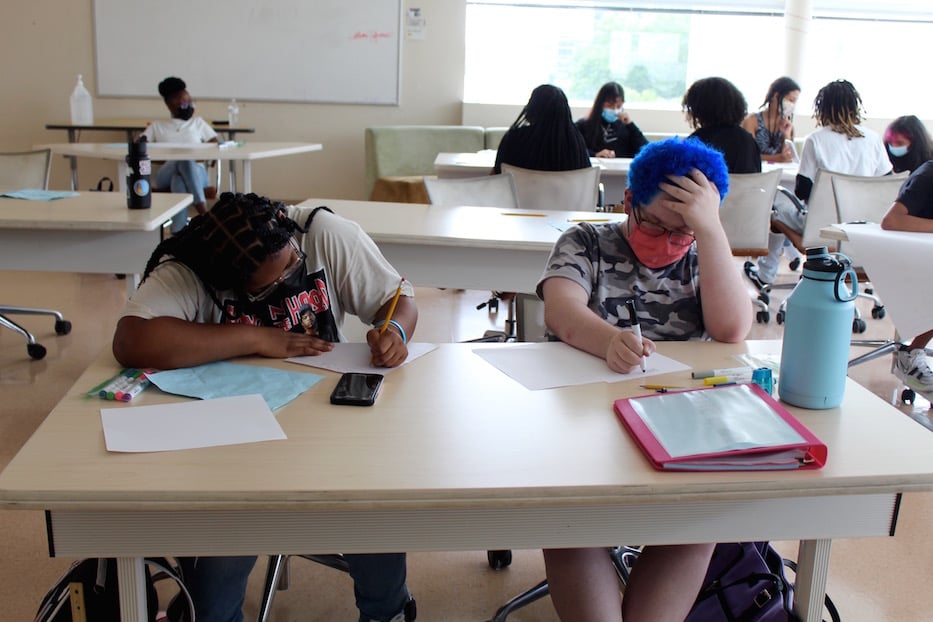

Sophomores Denise Ortiz and Hayden Earnshaw.

Hugs, fist bumps, and momentary squeezes rippled across the classroom. When sophomore Erica Arias hustled in and took a seat, the whole right hand corner of the room cheered her name, a rising wave of noise that could have been mistaken for a warmup. Last year, Arias remained online as some of her peers returned to the classroom in April. It was the first time that she and Alfred had ever met face to face. Alfred beamed and rose to address the class.

“Real quick, I would like to know what your personal claim to fame is,” she said. “For instance, I have been singing since I was four years old.”

She traced her own choral trajectory, from singing in a choir at four to a larger one at 12, to professional choirs and a path to music education in high school and college. Her love for choir followed her to the New Haven Public Schools, she said—first Truman School in the city’s Hill neighborhood, and later Co-Op downtown.

“It’s my life,” she said. “Right now I’m trying to be motivated because I don’t like this.” She paused and brought her hands to her mask. “I like to see your faces.”

Personal claims to fame bubbled up from her students, each followed by an immediate burst of applause. Some students noted that they were singing for the first time. Others had been singing since middle school. At the far side of the classroom, one student who said she had been singing “since I was very little” drew extra cheers. Many had started in their churches, where they still sing every Sunday.

When the class reached Arias, she said that it was her first time singing with a choir. Alfred corrected her: it was the first time she was singing in person. She had been singing through a screen for a year.

Pulling back from the exercise, she reminded students that all of them would need to take an assessment, regardless of skill level. She assured students that it wasn’t something to worry about: Co-Op was a place with a class for all of them.

“Don’t fret about it,” she said before students packed up and headed back out into the hallways. “Don’t be afraid of what you don’t know.”

And The Band Played On

Teacher Matt Chasen with students Jaiden Shoulders and Caleb Davis, Jr. and teacher Patrick Smith.

One classroom over, second period band erupted into sound as juniors and seniors launched into an F natural scale without screens, Zoom and Google Classroom logins, or mute buttons for the first time in over a year. As students took their seats, several cautiously lowered their masks and blew slowly, deliberately into their instruments.

Within minutes, they were running through scales, turning the classroom into a sound bath. While the school ordered dozens of specialized masks and stop covers for brass and woodwind instruments this year, Smith said he realized very quickly that they were ineffective. Flutists, for instance, couldn’t breathe properly in them. Droplets still escaped through the instruments' tone holes. When he asked students if they were vaccinated, he said that most hands in the room went up.

Monday, horn and flute mingled and floated through the air. At the front of the room, seniors Caleb Davis, Jr., Jaiden Shoulders and Vincent White, Jr. spread out across two keyboards and a drum set. The three, who play in church together each week, looked instantly at home. They hammered out ribbons of sound as other students waited for Smith’s direction.

Senior Anthony Rydlewski: "Online, I had trouble finding the motivation to practice."

A few rows back, senior Anthony Rydlewski leaned over his book, wearing his saxophone as if it were an extra limb. He said that Monday felt like a milestone—he hasn’t been in a full band classroom since March of his sophomore year. During his junior year, he struggled to practice at home as he took care of his young nieces. He stopped playing for the first time since the fourth grade.

“It’s awesome to finally be back in person,” he said. “Online, I had trouble finding the motivation to practice. When you’re by yourself, you don’t feel that same motivation or want to bother the neighbors at 9:30 in the morning.”

Moments later, Smith had him sliding into a smooth saxophone solo, the instrument wailing its return to Co-Op. Closer to the front of the classroom, Campos waited for her cue to come in. The number turned into a coordinated ballet. When Davis rose to exit the classroom briefly, drummer Vincent White ambled over to the piano, slipping into his place without missing a beat.

Shoulders, who had been on the piano, hustled over to the drums and settled in. A treble and bass clef drawn in black marker peeked out from a dry erase board right on cue.

When the band finished the piece, Smith looked around. He studied students’ expressions. After gently pointing to a mistake—"an accidental on an accidental,” he said, drawing a few easy smiles, scrunched faces and chuckles—he asked students to close their eyes.

“Raise your hand if you practiced during the pandemic,” he said. A few hands went up.

“How many people found that practicing your music helped you get through the pandemic?” he continued. A few students looked around; some kept their eyes closed. More hands went up. The band dipped into a chromatic scale to finish its first practice back.

Some students, who gig outside of school, said that music became a form of survival. Each week, Davis, White and Shoulders play at Trinity Temple on Dixwell Avenue and Agape Christian Center on Goffe Street. In addition to drums and piano, all of them play bass; Shoulders also plays trombone and trumpet and Davis plays sax and viola. White also plays in Southern Connecticut State University’s Blue Steel Drumline. It helped them get through the pandemic.

As the classroom emptied out, Smith said he’s not focusing on what some educators and parents have called a “lost year.” He motioned around the space, conjuring the music that had just filled it to the ceiling and crawled into its corners and crevices.

“My philosophy is you are where you are, so don’t mourn the past,” he said. “Every one of them has come back more mature than they left.”

The Quiet Art

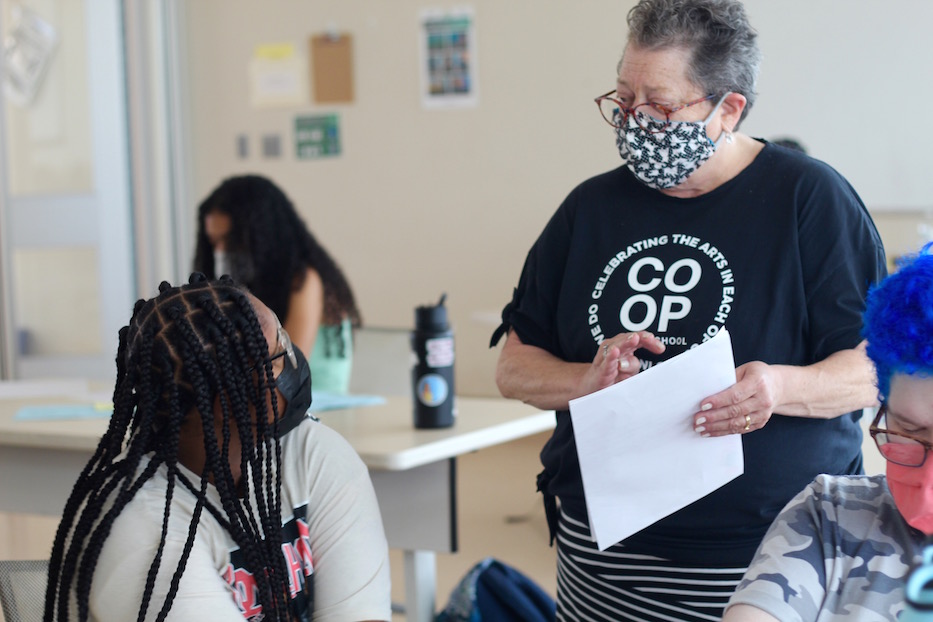

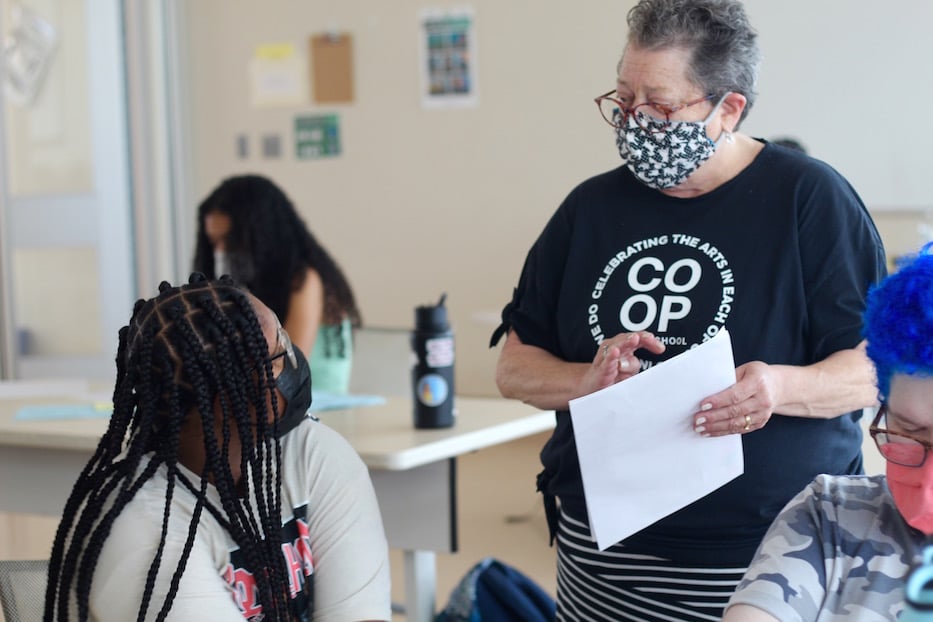

Freshman Teonna Costin with creative writing instructor Judith (Judy) Katz.

As almost two dozen seniors filed into a peer leadership seminar on the first floor, creative writing teacher Judy Katz prepared for a class of freshman in “the fishbowl,” a fourth-floor classroom so named for windows that look out onto College Street on one end of the room, and onto the hallway on the other.

A poet herself, Katz has spent the last several months writing a poem a day—including 70 inspired by the I Ching that she is hoping to publish in a book. In the fishbowl, she prepared to teach a mix of poetry, fiction, nonfiction and drama to wide-eyed first years, some of whom finished seventh and eighth grade online. Students trickled in, a few dragging their feet as others bounded through the doorway in glittering masks and bright backpacks.

Downstairs, seniors Piper Zschack and Ajibola Tajudeen fretted about the future of creative writing as they waded through their peer leadership seminar. The class, which is supervised by teachers Valerie Vollono and Ryan Boroski, gives seniors a chance to create in-school programming meant to strengthen the Co-Op student community.

Students Eva Berthelot-Hill and India Williams.

Among ideas for town hall meetings with teachers and administrators, Tajudeen said he worries that faculty forget about creative writing because it is such an understated art. While other departments have end-of-year performances, creative writers have the school’s literary magazine Metamorphosis and seasonal showcases. They are a far quieter art, he said.

“The creative writing department, every year that I’ve been here, it keeps getting eaten away at a little more,” Zschack said.

Back upstairs, the form hummed to life. Cassandra Clermont, who finished eighth grade in person at Davis Academy for Arts & Design Innovation Magnet School, said she selected creative writing because it’s something she already practices at home. A lover of science fiction and fantasy novels, she said that she’s ready for creative writing classes to push her to become a stronger writer.

“Are we alive after all this day?” Katz asked the class as students filled the seat, some sitting in pools of afternoon sunlight. She asked students how they were feeling on a scale from one to 10.

Cassandra Clermont.

The room was quiet at first. Then students tentatively raised their hands. Most were at a six or below, they half-mumbled. In the back row, freshman India Williams said she was at a nine. Katz smiled beneath her mask. When she paused and asked for favorite ice cream flavors, some of them sat up a little straighter. Suddenly, the room buzzed with mentions of chocolate, pumpkin, and at least three different kinds of cookie dough.

In the front of the room, Teonna Costin and Abbey Esposito jumped into their first graded assignment of the year: listing "roses and thorns" from summer vacation. They watched as Katz pulled colored markers, sheets of blank paper and small plastic baggies onto the desk. Students lined up at the desk, selecting four markers each that they could use for the year. Every so often, Esposito snuck in a page of Julia Walton’s Words on Bathroom Walls.

Costin, who matriculated from Benjamin Jepson Magnet School, said she was inspired to study creative writing by her sister, who graduated from Co-Op last year. As she bent over her page, a list of thorns bloomed across it. There was her sister’s departure for college, and a personal bout with Covid-19 in January of this year. Last semester, her best friend died from pediatric cancer, causing her to stop focusing in school. Her marker scratched and whispered across the page.

“It feels like time flies by fast, and I can’t take anything for granted,” she said. “It kind of made me see the world from a different image.”

Teonna Costin and Abbey Esposito sketch out their roses and thorns.

There are roses too, she said: her family spent the summer months volunteering at a homeless shelter on Dixwell Avenue. She’s excited to be back in a school building for the first time since March of last year, when she was finishing seventh grade at Jepson. She likes getting out of her house, where she lives with four brothers and a younger sister. She looked up as other students completed their papers, some illustrated with bright, blooming flowers and prickly vines, and turned them in.

“Ms. Katz, why did you start writing?” she asked.

“I had things to say!” Katz answered, eyes lighting up above her blue medical mask. “And I was quiet. I didn’t want to talk.”

There was a beat. “Do you have things to say?” Katz asked.

Costin smiled beneath her mask and looked down at the desk, then up again.

“Yes I do,” she said.