Co-Op High School | Education & Youth | Music | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

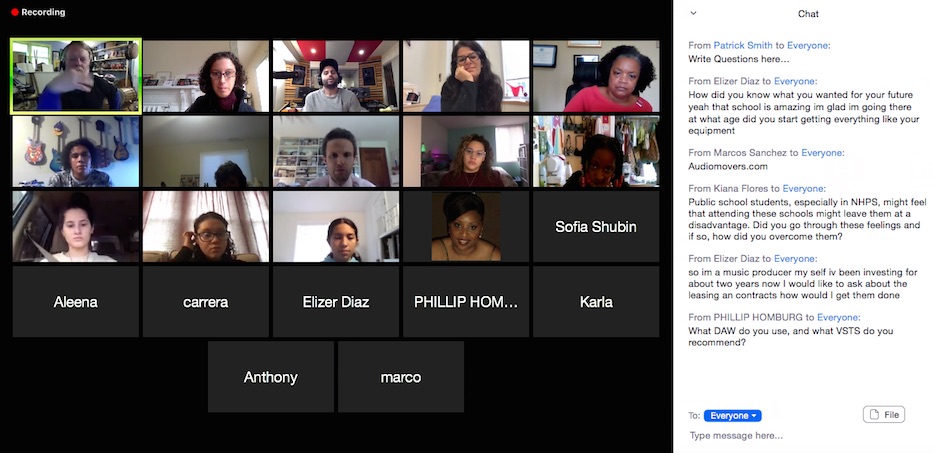

| Marcos Sanchez: “Co-Op is a huge part of what I do every day, and it helped me define what I want to do in the future.” Screenshots via Zoom. |

Marcos Sánchez turned to his neighborhood high school when he had dreams of breaking into the music industry. Nineteen years and one Latin Grammy later, he’s giving back to its students in a semester turned on its head.

Tuesday, the Grammy-winning producer and musician dropped in on music theory students and teacher Patrick Smith at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School (Co-Op), where classes have been remote since the beginning of the year due to COVID-19. In an hour-long conversation that spanned New Haven, Puerto Rico, production work, structural racism, and music theory, he encouraged students to double down on their studies even as they learn from home. He joined the class from his home studio in Puerto Rico, which he built seven years ago.

“It’s been a while,” he said at the top of the hour, gleeful as he greeted former teachers Smith and Harriet Alfred, who are both still at the school. “Co-Op is a huge part of what I do every day, and it helped me define what I want to do in the future.”

That attitude comes from his own experience in New Haven, where he was born 36 years ago. Sánchez grew up on Congress Avenue, the son of a Pentecostal Minister in a proudly Puerto Rican household. Church put music in his blood before formal education ever did: his first exposure to a drum kit and piano both came before his fifth birthday. It would be a decade before he heard anyone use the words “music theory.”

As a young kid, Sánchez attended Truman School, a large brick building that rises off Washington Avenue just before Ella T. Grasso Boulevard. It was there that he first met Alfred, who worked in the city’s elementary schools before transferring to Co-Op in the late 1990s. For weeks, he begged to use the piano that sat in her classroom.

Only after she relented did she realize that Sánchez could play—and wanted to build a life around the instrument. Tuesday, she praised his work ethic before cracking a warm, wide smile.

“Marcos, you look the same,” she said, keeping one eye trained on the screen as students arrived. “You got a little peach fuzz but you look the same.”

As students came in—”Cameras on!” said Smith with limited success—Sánchez dipped into his past to talk about his present. From Truman School, the young musician went to Roberto Clemente Leadership Academy and then to Co-Op. In the late 1990s, the high school was still nestled at the intersection of Orange and Bradley Streets, in a building that now houses New Haven Academy.

He met Smith his sophomore year, when he was starting to produce demo tapes and Smith was a new face in the hallways. During the day, Sánchez worked for hours on his demos, sometimes staying at the school until nine at night. He recalled spending afternoons at Neighborhood Music School, where he was a student with Jesse Hameen, and then returning to the Orange Street building to rehearse, record, and hone his music theory skills.

He remembered learning to read charts that he now has a version of in his studio. Earlier in the session, Smith and Alfred had joked that they sometimes thought of just keeping a cot at the school, because dedicated students worked so late into the evening.

“I knew that was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life,” he said of his time at Co-Op. “There’s no excuse. You gotta make it happen, [and] believe in what you’re doing.”

It was during those years that Smith gave him a mantra that he now lives by. Smith told Sánchez that artists don’t have control over when they’ll get a call that could change their careers. What they can control is whether or not they’re prepared to take it.

Tuesday, Smith added a second saying: “It’s not the school you’re going to. It’s the person you take to school with you.”

The Latin Grammys first started in September 2000, in the fall of Sánchez’s senior year and just two months shy of his 16th birthday. Before he graduated in 2001, Sánchez told Smith he was going to win one of the awards. Smith listened intently: he believed the young musician’s words. He watched as Sánchez signed a contract with Sony and produced large-scale events including American Idol in Puerto Rico. When the musician won that Grammy in 2018, he brought his music theory teacher to the ceremony.

As he spoke, Sánchez focused on the importance of focusing on rehearsal, music theory training, and collaboration even when COVID-19 may make it feel impossible. He pointed out that musicianship is never a solitary act: he always works with a team, whether it’s in the studio or on a stage. It’s an approach that he picked up at Co-Op, somewhere between “trying to be the best pianist” he could be and refining his skills on trumpet, saxaphone, guitar and drums.

“It’s all teamwork,” Sánchez said. “What’s happening in our brain when we are in a band or an ensemble is that we are asking: what is our function?”

He told students to keep making and recording music from their homes, even with minimal equipment and improvised recording setups. Theory is part of that equation, he added: he’s landed gigs that other artists are unable to take because he can sight read music and has a sharp ear. Smith noted that students have been leaning into that on-the-fly approach with a multi-part recording of “Oye Como Va” that he is now tracking and sewing together.

Those same skills have helped Sánchez during the pandemic. When COVID-19 hit the United States in late February and early March, he was on tour in Mexico. Within days, he flew home to Puerto Rico. His studio was quiet for the first time in years. Work on his calendar disappeared. He estimated that he lost $15,000 in a single week from cancelled performances.

In the strange quiet, he realized that he had rare, unstructured time to practice. He pulled out music theory books. He started studying Johann Sebastian Bach, a factoid he shared with the class in the same tone one uses for eating Wheaties. He looked up new works that he could sight read just to stay fresh. He played his scales, and then played them again.

He also stuck with a daily ritual—going for a run, and listening to top 40 songs just to analyze them. Instead of allowing himself to fall into a COVID-19 funk, he pushed himself to practice his skills each day. He urged students to do the same.

When record producers started coming out of hibernation, he was waiting. From his home in Puerto Rico, he worked with artists who have spent the past eights months recording beneath blankets and in closets. He landed a major record deal for a Spanish-language album that has yet to be released (Co-Op students have the exclusive scoop, he joked; the rest of the world will have to wait for it).

Because he can master a piece of piano music quickly, he’s made up for lost revenue by tracking songs and turning them around to fellow musicians. The hours are long, he said—he wakes up at 6 a.m. and sometimes doesn’t leave the studio until after midnight—but he loves what he does.

As he spoke, questions poured into the chat. Between queries on recording equipment and his backup plan (there really wasn’t one, he said), senior Kiana Flores virtually piped up. Flores lives in the city’s Fair Haven neighborhood, where she is active in the New Haven Climate Movement.

“Public school students, especially in NHPS, might feel that attending these schools might leave them at a disadvantage,” she wrote. “Did you go through these feelings and if so, how did you overcome them?”

Sánchez was quiet for a split second, mulling the question over in his mind. Then he reached behind him, and grabbed a glinting, pint-sized gold gramophone. It was the Latin Grammy that he won two years ago for Victor Manuelle’s 25/7. In addition to his production work on the album, Sánchez played piano on several of the tracks.

“The reason I’m doing this is I come from the New Haven Public School district,” he said. “I grew up on Congress Avenue. I’m straight from the Hill. I never see myself as a disadvantage. I feel that if you really want it, you’re gonna make it. You gotta stay focused. Don’t let anything block your sight.”

He added that it doesn’t mean music making has always been easy for him. Sánchez’s undergraduate work at the Hartt School ended after a year, when he became a father to a baby boy who is now a senior in high school. He has worked long, often grueling hours with other musicians. He acknowledged that he has also encountered fellow producers and executives who underestimate him because he is Puerto Rican.

Smith told the class a story from 2018, the same night that Sánchez won his first Latin Grammy. He was with Sánchez in Las Vegas, the only white guy in a group of eight to 10 people. They'd gone to a restaurant to eat, and found it packed. When they spotted an empty chair beside a white patron, Smith asked for it without hesitation.

No one else in the group was comfortable asking for it, he said. He called it representative of the systemic racism and microaggressions endemic to not just America, but also to the music industry.

“I can’t compare that to what the African-American community is going through,” Sánchez said, noting that he has remained very close with fellow Co-Op grad Aaron Mitchell, an executive at Netflix who is Black. “They deal with it at a different level. I’ve dealt with it, and it’s tough.”

His answer, he said, is in his music. While there are biases within the music industry—Argentine producers “think they’re the Europeans of the Latinos,” he joked—he spends time honing his work instead of fixating on them. If a musician is good enough, he said, that’s enough to get any of their detractors “to shut up.”

“If you can’t respect me, then with all due respect, I’m out,” he said. Then he turned back to the class. He summoned some Bossa Nova, the notes ready beneath his fingertips. He urged them to keep up with their studies.

“It takes a lot of discipline,” he said before playing the class out. “If you don’t build that up in high school, it’s not gonna happen.”