Arts & Culture | Neighborhood Music School | COVID-19

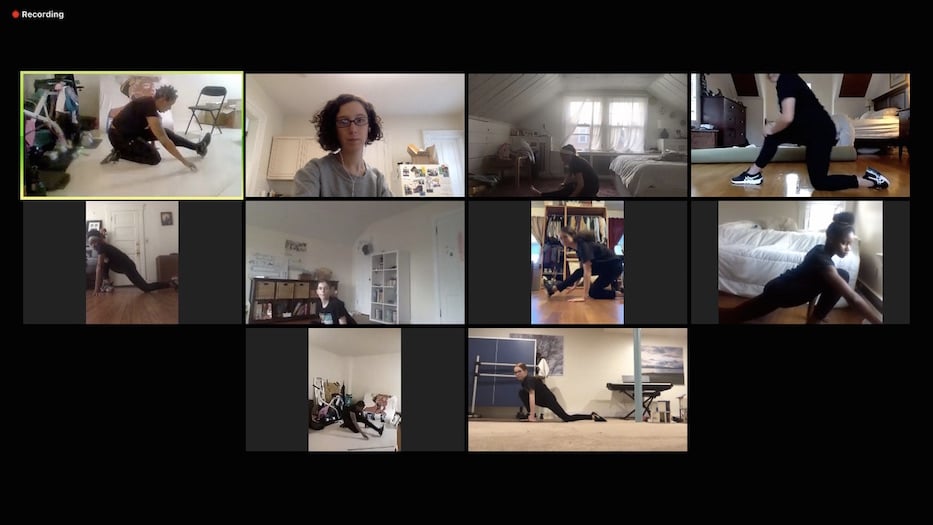

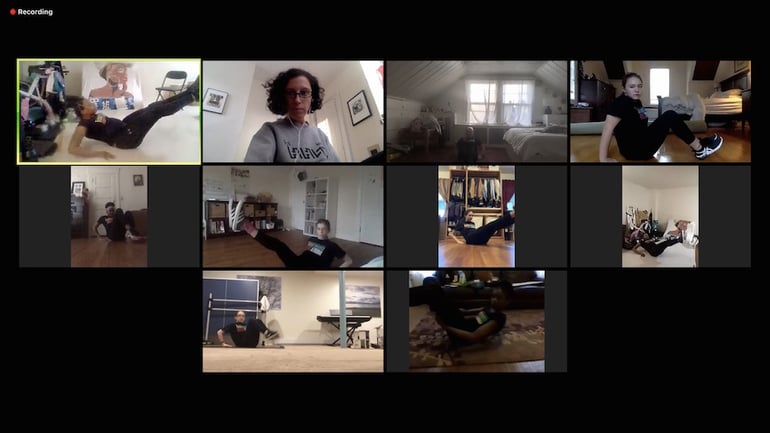

| Hanan Hameen teaches on a recent Monday. Screenshot from Zoom. |

The dancers stretched in one-inch squares. Ankles flexed. Legs extended. Arms windmilled. In at least one room, someone’s feet got close enough to the camera for toes to appear. Hanan Hameen pressed her face close to the screen and counted the students. Someone was missing. She waited for another minute, and then got started.

“So how’s everybody doing?” she asked. “How are y’all holding up? How are we?”

Hameen is one of the teaching artists at Neighborhood Music School (NMS) who are learning to dance, play, act and sing in virtual space. For two months, she has taken her weekly hip-hop and repertoire classes online, navigating a virtual world of intimate, in-person arts education through screen time and glitchy internet connections.

“Teaching online is definitely different, because you don’t have that in-person connection,” she said in a recent phone interview. “I’m a very hands-on teacher. They [students] love to hug each other and show their love. To be online, we have to rely a lot on me showing them the vocabulary.”

Hameen last year at an opening of the Blake Street Pocket Park. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

Each class comes with a new challenge. Before COVID-19, Hameen drove into NMS twice weekly from New York, where she grew up and is now staying in isolation. At the school, she would greet her students in the studio, then launch into choreography that they were working on together.

There were parts of teaching she took for granted, including being able to reach over and correct a student’s posture, or practice a step by their side. In her repertoire class, students were working on a dance that included a lift. In another piece, one student played a puppet master while another played a puppet. They can't do that over a screen.

Now, she logs into Zoom from an apartment in the Bronx, surrounded by home exercise equipment that helps her fight a decades-long battle with Lupus. Across a network of routers, wires and screens, students log in from their bedrooms, basements, and living rooms a state away. Most are in New Haven and Hamden; not all of them have stable internet connections.

More than once, a student has warned Hameen that their phone might die before the end of the lesson.

During a recent class, the group opened on stretches, trading bits of information as they stretched, lunged, and shook out a day of distance learning and quarantine. Naomi Gitelman, one of the class’ dance captains, spoke about how good it had been for her to catch up with a friend she hadn’t heard from in a while. Lily Liu-Ballard had just found out that she’d been admitted to New Haven Academy. Naomi Borenstein had gotten into the Educational Center for the Arts.

It felt like a reunion. Hameen scanned the Zoom space and called students by nicknames that she’s been using for months, and sometimes years. Zara, became Z-Money. Another, named Janae, was suddenly Nae Nae. A few minutes in, another one-inch square popped into the screen. Dressed in a black NMS shirt—the class' de facto uniform—Alana Rose appeared with a huge smile on her face. Hameen cued up Alessia Cara’s “Wild Things” and got down to business.

In a screen full of tiny squares, students moved to the lyrics. Arms lifted toward the ceiling. Legs and torsos sunk into deep lunges. Shoulders loosened after a day spent at computers. Backs straightened. The track switched; suddenly Jussie Smollett was belting “Sometimes you feel insecure/trust me girl I understand!” Hameen began to hit the floor with a yardstick to the rhythm.

“I want to see your knees to your chest!” she said into the screen.

Across the squares, knees lifted on command. She switched to jumping jacks. In eight frames, legs unlocked and flew into motion. The track flowed right into the Black Eyed Peas. At one point, the song cut out without warning.

“If something happens with the music, the WiFi, just keep dancing,” she said. “The point is just to keep dancing.”

When the class first switched online in March, Hameen concentrated on existing choreography. Her model is peer-centered: dance captains lead the class, and she steps in only after other students have tried to answer questions their classmates have. In the past weeks, students have been adding new parts to a piece dedicated to social media, online bullying, and school shootings.

In the dance, titled “ICEolated,” students work backwards, showing how online and in-person harassment can lead to physical violence and school shooter situations. As they work through it online, the piece’s title has taken on an entirely new meaning.

It’s not alone: the dance department, which is also responsible for NMS’ multi-site “Dancing With Parkinson's” program, is still figuring out how to put performances online. Hameen praised her students for adapting to the technology that they have.

“I’m just grateful that I was able to share the love of dance and the therapy that comes with it,” she said. “I want them to experience dance families. It’s about: how do you become your best self and help everybody to improve? It’s a give and take. We all learn from each other. It’s helping them to cope now. This thing is affecting all of us. We’re all traumatized now.”

In the meantime, she said, the classes also help keep her sane. Many of the symptoms of Lupus mirror the symptoms of COVID-19. Her muscles ache constantly. Her temperature spikes multiple times a week. She is used to becoming short of breath. Her daily routine entails battling exhaustion. She is never not in pain, she said—so “how would I even know?”

That exhaustion is also emotional, she said. She misses her parents, who are both in Connecticut (her father is also a teacher at NMS; her mother is a writer, filmmaker, and organizer in the community). While taking out the garbage last month, she learned that a neighbor had died.

She got back to the apartment, made sure her hands were clean, and broke down. The next day, she taught a class for three hours. She danced for her life.

“Being with my students, it changes everything,” she said. “It changes everything. They may need me. But even more, I need them. I need it. I need that connection. I’m getting them to a place where they can feel better and they can feel a sense of normalcy. The uncertainty of the world is one thing. This is a place where they can have some control over what they do.”

“An Incredible Whirlwind”

/NoahB.jpg)

| Noah Bloom photographed at NMS last year, when he took over as ED. When he goes into the building to check mail, "I still get all sad and tingly," he said. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

Hameen’s approach reflects a shift in teaching that is happening at NMS more broadly. On March 13—ominously a Friday, and the same day that New Haven Public Schools closed across the district—the school closed its Audubon Street doors indefinitely.

At the time, NMS employed close to 200 instructors and was serving 2,300 students, including 1,200 students who were taking one-on-one lessons and students enrolled in its preschool and middle school programs. Since taking the helm last summer, Executive Director Noah Bloom had been dedicating its fundraising efforts to raising the number of need-based scholarships the school is able to offer. COVID-19 meant that effort would go on the back burner.

By that weekend, Bloom had started the process of furloughing over 50 faculty and administrative staff members, with a commitment to paying their healthcare as long as the school was able to (eight weeks in, he said that commitment remains). He spent a week calling them, breaking the news to each person. Meanwhile, he shrunk the school’s leadership team and had everyone take a pay cut.

“The expectation is that we will bring back everyone we can,” he said. “These are people who built the institution and have done so much for it.”

With a skeleton crew that remained, he asked teachers to prepare content for one-on-one and group classes in music, voice, and dance. He made a decision to close down the preschool entirely, with no online option. Teachers at ATLAS, the organization’s private middle school, prepared to go virtual immediately.

“It’s been an incredible whirlwind,” he said in a phone interview. “We’ve been doing deep thinking about how we continue to maintain relevancy and try to connect with more and more people. The spectrum of what we are trying to do is so wide, and that’s been quite a journey. We’re artists and we’re adaptable. It’s really a range.”

Student Christopher Rogers in a recent voice recital.

He acknowledged that the time has also been particularly trying for faculty, many of whom were part-time, contract employees who are suddenly without reliable work. Where they once met with students in person, many instructors now have found themselves recording duet tracks or accompaniment for live lessons. Recitals are programmed with background tracks. Ensemble rehearsals require a delicate balance of muting, unmuting, and close looking—all over internet connections that may or not be reliable.

As teachers settled in, students started coming back. Of the 1,200 students taking one-on-one lessons before COVID-19 closures, about 900 have stayed on. More have returned for group classes. Some have been shut out of their lessons because of the digital divide. Others have instruments that are still sitting in their cases inside closed public schools.

As he tries to work through the fact that “all the equity issues at the forefront of educational opportunities are accentuated now,” he’s also working to bring in funding. NMS has expanded its reach to Hartford and Fairfield Counties, with new enrollment from students who want the connection. Since mid-March, the school has received $600,000 in Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) relief funding and raised $65,319 in the Great Give.

At ATLAS, students are in class from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. each day. Bloom knows that firsthand; his oldest child is in the program. He said they are trying to troubleshoot some of their performance issues in real time—like the fact that students were supposed to do A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Long Wharf Theatre at the end of the school year (it helps that they spent the fall reading dystopian fiction, he joked).

The show will go on, Bloom said—he and ATLAS staff just don't know how or when.

Initially, he said, he also worried about a technological generation gap. Twenty-five percent of the organization’s students are over 65 years old, and use classes as a way to socially connect and continue lifelong learning. But many of those students have come back online, performing for each other in classes and recitals that are now held over Zoom.

If the sound quality isn’t always there—Zoom and Google Hangouts both use compressors, which makes audio tricky—Bloom suggested that the emotion still comes across.

“We haven’t had to define ourselves as essential,” he said. “Our audiences have done that for us.”

While the state may start its four-phase reopening on May 20, virtual classes will likely continue for much longer. As of this week, the school has not yet made a decision on whether or not to run some version of its Audubon Arts summer program, which is typically 15 percent of its overall budget. He acknowledged that any program will look drastically different than it has in years past, because large groups cannot be part of the program.

He also doesn’t know what long-term closures may look like, if waves of COVID-19 prove to be cyclical. In the interim, virtual classes fill part of that void. When he goes into the building to check mail, he said he still gets "all sad and tingly" thinking about how long it may be until the classrooms are safely full.

“We’re not first responders, but I do think the arts and culture are so critical at this time,” he said. “We have to keep making art if we want things to change. And we have to be real patient because it’s gonna take a long time for things to change. It’s like the preventative medicine that society needs.”

“All of the other work, whether you’re in a pandemic or not, has to happen in conjunction with the community,” he added. “I know we’re going to be asking them and working hard to serve them.”

The Rhythm Of A New Normal

Across the region, the model has become the new normal for hundreds of students who are continuing their lessons online. Some have been working with their teachers for over a decade; some have just started in the midst of distance learning.

On a recent Monday, 18-year-old Anton Kot sat down with his drum kit and called his teacher, Jesse Hameen II. Kot is a senior at the Educational Center for the Arts, meaning his commute to lessons was once as simple as crossing Audubon Street. Hameen first took him on as when he was seven. The two have been working one-on-one for 11 years, a near-weekly presence in each other's lives.

In the months before the pandemic, Hameen worked with Kot on his audition tapes for college. One of them earned him a full scholarship to the Steinhardt School at New York University. As they work through their final months before he goes—if classes are in person at all—there are the logistics of positioning FaceTime, accounting for volume issues, and hoping the internet won’t get glitchy.

“It leaves an opening for new opportunities,” Kot said. “There’s this whole other aspect of online learning that I didn’t expect. It’s allowed me to pay more attention during the lesson—I’ve found myself to be more focused on what’s going on. I think it’s given me a chance overall what’s being shown to me in a different sense.”

During a recent lesson, the two resumed work on a piece by the drummer Ari Hoenig that Kot has been interested in. In the past weeks, they’ve also been doubling down on rhythms that let Kot work on triplets and quarter notes. He said that he’s trying to concentrate on the positives of online learning, like the fact that Hameen can send him clips and images to work from, or that he finds himself practicing as soon as a lesson has ended.

Hameen, who is taking on online teaching for the first time, said that the experience has pushed him to teach with a different vocabulary, not unlike his daughter’s approach to dance. He praised Kot for continuing to work, noting that “I would send him straight to the NBA” of music.

“Situations teach you how to teach,” he said. “The environment dictates the work you do. I teach to a person’s heart and ability. I try to teach where the student is alive. I try to think outside the box—and the universe is the box.”

Hameen added that what he is able to do over FaceTime or Google Hangouts with Kot is very different from what he’s able to do with a new student, like the 9-year-old he took on this week. When teaching, he listens for every student's rhythm. He tells them to trust their ears. He trusts his, too—and observes how they are playing through the screen. He makes it work across the distance.

“There’s nothing that beats one-on-one and in person,” he said. “But it’s a great opportunity. This is a great growing experience."