Education & Youth | ARTE Inc. | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism | Education

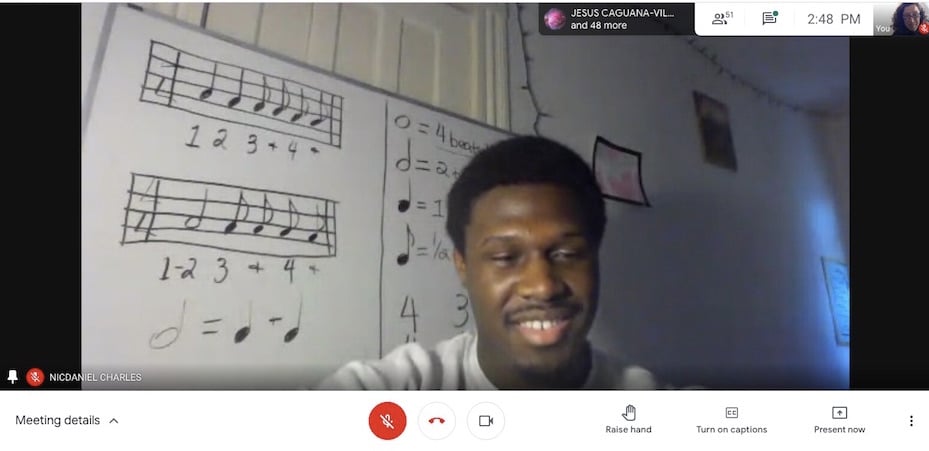

Nicdaniel Charles drew a fleet of blue eighth notes on a makeshift music scale. In a glowing one-inch box beside him, Mia Rivera watched carefully. Her pink headphones glinted above her matching pink t-shirt. A few boxes away, Lysha Owuor tracked the notes one by one as they appeared. Charles looked away from the score and peered into the screen.

Nicdaniel Charles drew a fleet of blue eighth notes on a makeshift music scale. In a glowing one-inch box beside him, Mia Rivera watched carefully. Her pink headphones glinted above her matching pink t-shirt. A few boxes away, Lysha Owuor tracked the notes one by one as they appeared. Charles looked away from the score and peered into the screen.

“Can someone, a brave soul, demonstrate what this would sound like?” he asked.

After a beat, Mia raised her hands and began to clap out a rhythm. Her painted nails shifted in and out of focus on the downbeat.

Charles is a senior at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School. Mia is a fifth grader at John C. Daniels School. The two are learning from each other as part of ARTE, Inc.’s weekly Saturday Academy, relaunched online due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Almost 11 months after the pandemic first hit New Haven, ARTE co-directors David Greco and Daniel Diaz have shaped the program around peer- and student-led instruction and social and emotional learning. The second has become a pillar in New Haven’s educational approach to Covid-19.

“We’re planting the seed,” Greco said over Google Meet on a recent Saturday. “We’re putting instruments in the hands of the kids that don’t have them. We insist that the kids have their cameras on. It’s about social and emotional learning. I think that the engagement piece and the social connection piece is so important.”

The model works on a tiered structure, just as it did in person prior to last March. Each Saturday afternoon, a fleet of high school and college students teach the bulk of courses, working under the supervision of New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) music teachers Dan Kinsman and Matthew Chasen. In turn, their students are elementary and middle schoolers from the city’s public schools. Currently, ARTE offers instrumental and vocal music; Greco said they are adding visual art this session.

The format is meant to create an arts incubator that looks more like New Haven than many of its classrooms. As of 2019, the Connecticut Department of Education reported that 46.3 percent of NHPS students identified as Latinx, while 37 percent identified as Black and 12.9 percent identified as white. That number is flipped for educators: 75.5 percent identified as white, while 14.6 percent identified as Black and just 8.6 percent identified as Latinx.

At ARTE, "if you look at this screen, it is like a carbon copy of New Haven public school,” said Diaz. Several classes are offered in both English and Spanish, with teachers who shift between the two languages when they need to. Some of the teachers went through ARTE’s program themselves; others jumped into teaching with the organization because they want students of color to see themselves reflected in their mentors.

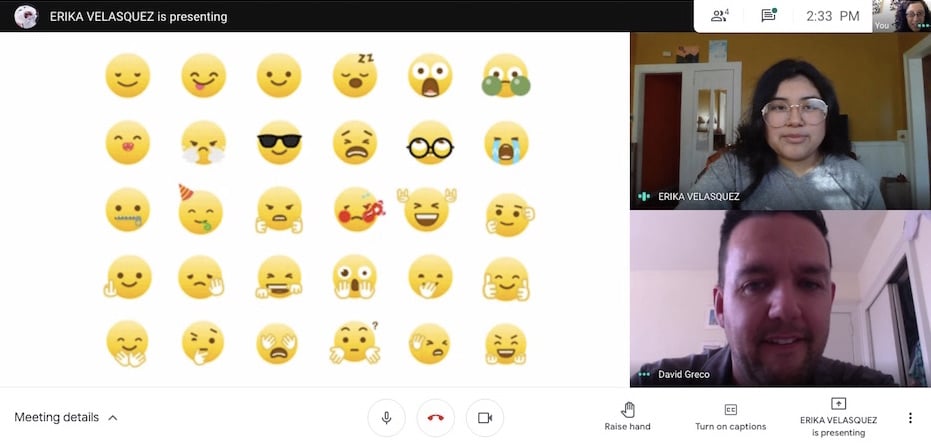

Each one of them has relative flexibility in their work. Saturday, Wilbur Cross High School junior Erika Velasquez started her recorder class by pulling up a page with emoji characters, checking in with students through the cartoonish yellow faces. As students logged into the class, she gave them a chance to pick out the face that they most identified with.

Each one of them has relative flexibility in their work. Saturday, Wilbur Cross High School junior Erika Velasquez started her recorder class by pulling up a page with emoji characters, checking in with students through the cartoonish yellow faces. As students logged into the class, she gave them a chance to pick out the face that they most identified with.

Some went for the smiley icons. Others veered toward the sleepy, red-cheeked, and frowning faces. Velasquez walked students through a self-soothing exercise, each lifting each of her hands on screen and shaking it out. She said that the exercise reminds students of their physical bodies in a time when they may feel isolated or far from their classmates.

“It’s upsetting when that happens,” she said after class. “You can’t be there to comfort them. My way of helping them cope is, I say, ‘Do you want to talk about it?’ You know, you can send private messages, and I talk to them that way. Or I try to change the subject, where I can make them de-stress. I say, nothing’s going to harm you. You’re safe here.”

She also uses music to ground the students. Saturday, she pulled a copy of a copy of “Old MacDonald Had A Farm,” holding her recorder up to the screen to model the fingering. Because students aren’t in the same room, she can’t help them reposition their instruments in real time.

The virtual pivot has pushed her to listen closely, and try to talk students carefully through what they might be doing wrong. Saturday, she focused as students worked through the melody, some playing it for the class.

In another Google Meet classroom, Wilbur Cross junior Gabriella Xavier pulled up “María Tenía un Corderito,” (Mary Had A Little Lamb) writing out the lyrics in a Google Doc as she played the song for students. Framed by four white walls, she sang the notes into a screen, her voice clear as a bell. She asked who wanted to try a few bars. Students hesitated for a moment.

In another Google Meet classroom, Wilbur Cross junior Gabriella Xavier pulled up “María Tenía un Corderito,” (Mary Had A Little Lamb) writing out the lyrics in a Google Doc as she played the song for students. Framed by four white walls, she sang the notes into a screen, her voice clear as a bell. She asked who wanted to try a few bars. Students hesitated for a moment.

“I am putting the letters in Spanish just in case,” she said, urging them to follow along.

Juliet Garza Pluma took a deep breath and unmuted herself. She jumped into the song. Xavier beamed, her face so close to the screen it seemed for a moment like she could have reached through.

“Teachers! Be Brave!”

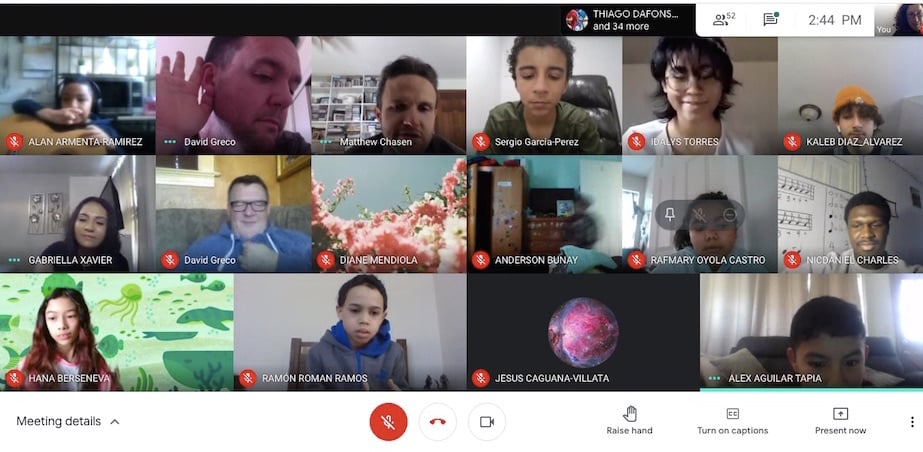

When students finish their classes, they head back to the main session for an arts show-and-tell before they log off. Prior to last March, ARTE held the same sort of final session in the large recreational room of the Atwater Senior Center in Fair Haven. Now, they listen to each other from one-inch boxes. Miraculously—and because it is one of the program’s rules—almost all of the cameras remain on.

Greco said he tries to add incentives, like a recent pizza-themed trivia game that ended in pizza delivery for three students. The main session also alerts supervisors to holes the program is still trying to patch, including NHPS students who need instruments for their classes. Kinsman, a teacher at Fair Haven School, has organized a series of socially distanced drop offs.

“Welcome back!” Kinsman greeted them on a recent Saturday. “You guys did such a good job in your classes … who wants to show and tell?”

There was a beat as he looked around at the faces that crowded the screen. The chat, which had been aflutter just moments before, slowed to a hush. Mics remained off. A smile teased at the edges of Kinsman’s mouth. He scanned the screen, waiting for a volunteer.

There was a beat as he looked around at the faces that crowded the screen. The chat, which had been aflutter just moments before, slowed to a hush. Mics remained off. A smile teased at the edges of Kinsman’s mouth. He scanned the screen, waiting for a volunteer.

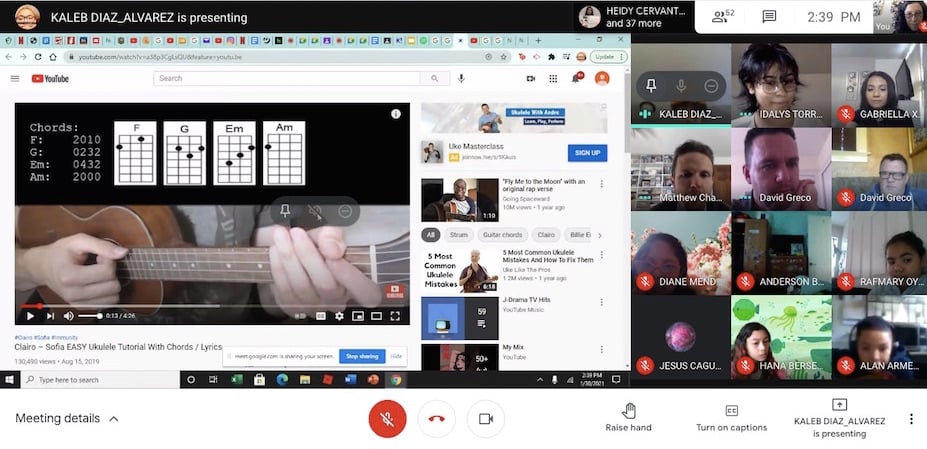

Kaleb Diaz unmuted himself. A junior studying strings at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School, he teaches all-ages ukulele in the program. He’s been working with his students on Clairo’s “Sofia,” an indie rock ballad that was written in 2019, when gathering didn’t seem like such a scandalous thing to do.

“I’ll be brave, because my students are ready,” he said.

The strings crackled, tinny but certain as he brought the small instrument to his chest and began to strum. He eased into the lyrics, his voice undulating as they washed over the screen. Over the internet, it drifted in and out of the speaker, still clear as he sang. Students clapped at the end, dozens of hands moving across the frame.

“Raise your hand if you can think of singing that song,” said Kinsman after applauding. “Teachers! Be brave!”

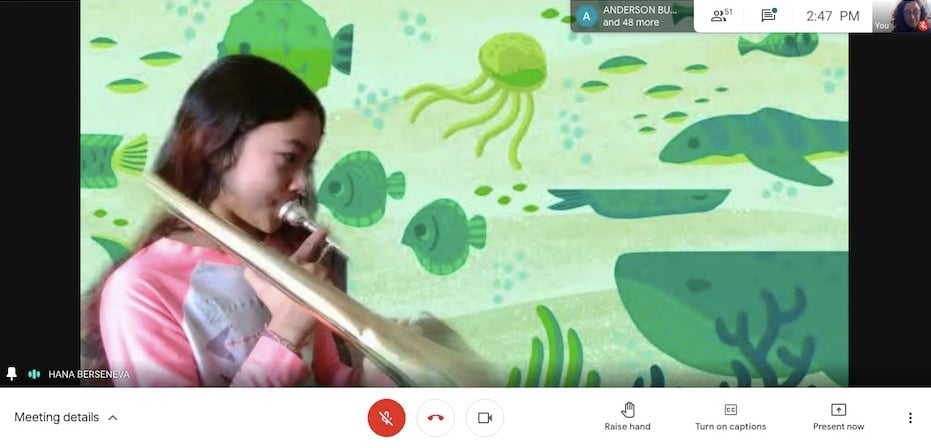

It was as if Diaz had opened a valve. Third grader Alan Armenta-Ramirez hopped into a version of “Happy Birthday,” checking in with Kinsman on the possibility of an instrument drop off in Fair Haven later that week. Student Hana Berseneva jumped into a rousing version of “How Far I’ll Go” from Moana.

It was as if Diaz had opened a valve. Third grader Alan Armenta-Ramirez hopped into a version of “Happy Birthday,” checking in with Kinsman on the possibility of an instrument drop off in Fair Haven later that week. Student Hana Berseneva jumped into a rousing version of “How Far I’ll Go” from Moana.

Elementary schooler Richard Rodriguez de Fonseca backed up from his screen, pulling up a clarinet. His mom began to record on a phone, bouncing a baby on her hip. Mia sounded out the final rhythm that she’d worked on in class. When she added an extra three notes, Charles gently suggested she try again.

That’s part of the program's mission, Kinsman later said. Students get excited when they see fellow NHPS students, some of whom are only a few years older than they are, making music. It encourages them to practice during the week, when their teachers are students themselves, making it through the daily slog of remote high school. He pulled up a video that Xavier, a junior at Wilbur Cross High School and the Educational Center for the Arts (ECA), recorded in Texas a few months ago. The song was a collaboration with the guitarist Chris Rocha, who runs a Christian label in Texas.

In the video, Xavier stands in front of a band in a white blouse, her arms lifted to the sky. She begins to sing in Spanish, pulling her arms over her heart. The scene shifts: she is looking longingly out of a window, a denim jacket pulled snugly over her shoulders. Her voice lifts off and crescendos. As the final notes rang out over the screen, students and fellow teachers raised their hands in applause. Some gushed in the chat.

“I’m gonna say, I knew you when,” Chasen said. “Boys and girls, that could be you. Gabi was exactly like you. Gabi worked really, really, really super hard.”

“It was cute and it was amazing,” student Diane Mendiola chimed in. “And it was in Spanish, and it was so adorable. It was like Ariel from The Little Mermaid.”

Filling A Gap

In a conversation after class, teachers said they come to their classes for themselves as much as for their students. It’s a model that Diaz refers to as “upwards mentorship:” as an administrator in the city’s public schools, he wants to encourage students to become educators by giving them on the ground experience as early as possible. That’s especially true when they are interested in arts education, where years of specialized training often become a socioeconomic hurdle.

In a conversation after class, teachers said they come to their classes for themselves as much as for their students. It’s a model that Diaz refers to as “upwards mentorship:” as an administrator in the city’s public schools, he wants to encourage students to become educators by giving them on the ground experience as early as possible. That’s especially true when they are interested in arts education, where years of specialized training often become a socioeconomic hurdle.

At ARTE, classes are filled with educators who seem much older than their teenage years. When he logs on to his computer, Charles transforms his own remote learning setup into a music classroom with a whiteboard, a few dry erase markers, and an internet connection. He said he’s learned from his own teachers at Co-Op and Morse Chorale, where he’s studied under Stephanie Tubiolo for the past eight years.

In front of students, he is patient and methodical, swiveling between the board and the screen as students clap out rhythms. When they mess up, he notes that they’ve added or subtracted extra notes before asking them to try again. The word “mistake” isn’t part of the class’ vocabulary.

After high school, he plans to follow in an older sister’s footsteps and study music education. At home, he tries to flex his teaching muscles with his younger siblings, who are also learning remotely during Covid-19. He said that he has that same kind of “brother-sister relationship” with some of his younger students at ARTE.

"I have one student, and as soon as I come on, he says something slick, and I say something slick back," Charles said, laughing a little. “I’ve always loved passing what I know. It just feels good to have someone see what I do, they go out and learn more about it.”

He’s doing it while taking classes and finishing college applications himself. He joked that it’s given him a new appreciation for how hard it is to teach students when they don’t turn their cameras on—and also reminded him of the value of representation in the classroom. At 17, he’s only had three or four teachers of color. He wants to do for students what many of them did for him.

He’s not the only one. Sergio Garcia-Perez, who teaches guitar, is a freshman at Guilford High School. As one of the few non-white people in his town, he said he instantly relaxes when he has a teacher of color. When he pulls out his guitar and teaches his class, he’s showing his students that they have the same right to be in those historically white spaces.

“I could relate to them more,” he said. “The biggest part of ARTE is just getting that connection with the students.”

Others feel like they are giving students a chance they may not get in their classrooms. Xavier said she sees herself in the students, particularly the ones who are shy and quiet when they begin her class. Like Charles, she has spent several years in Morse Chorale, and said that Tubiolo pulled her out of her shell.

“When I was presented with this opportunity to teach, these students reminded me so much of myself when I was younger,” she said. “I’m part of this safe space.”

Now a sophomore at Wheaton College, brass teacher Juan Pablo Rodriguez said he wouldn’t be studying music had he not been part of the Music in Schools Initiative (MISI) through Yale University. When he was in that program, sometimes his teachers were only five or six years older than he was. Now, he sees that same age difference in his eldest brass students.

“The mentorship aspect of the program is probably one of the most effective in teaching a student,” he said. “We can kind of return that same mentorship not as teachers, but almost as peers.”

Velasquez, who teaches alongside her 14-year-old sister Paola, agreed. While remote teaching is difficult for her—she can’t be in-person to soothe a student who is having a bad day, or correct poor posture—she wouldn’t trade it.

“You get to be involved in a kid’s life,” she said. “That’s a future generation, you know? I think it helps me a lot. Sometimes, you need that new energy.”

To learn more about ARTE, Inc., visit their website.