Culture & Community | Ely Center of Contemporary Art | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

The artist Jihyun Lee, whose show Interstice is one of several running at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art (ECoCA) through December 18. Lucy Gellman Photos.

At first, it seems like a tangle of stuffed and embroidered limbs, the cotton batting pressed snugly against the fabric in which it is encased. There is a donkey-shaped body in the corner, its head hanging down on its chest; a floating head stuffed into a purled gray sock; a horse-elephant hybrid suspended upside down. A pair of legs, dressed in bright red stockings, appears to drift in midair, and it takes a moment to find the head to which they are attached.

The longer a person looks, the more each detail reveals itself: the faces, rendered in sunny, blotted watercolor; the suggestions of full lips and wide eyes; beads and baubles that become body parts. A crown of red, pink, blue and orange yarn adorns one face; orange braids frame another. Light filters through the stand, casting huge, dramatic shadows onto the wall.

The work is part of Interstice, a solo exhibition from artist Jihyun Lee running through December 18 at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art (ECoCA). A poignant meditation on making and memory, it has become an affecting goodbye to the 51 Trumbull St. space, which will officially close its doors to the public later this month. At that time, the collections will move to the first floor of CitySeed, located at 162 James St. in the city’s Fair Haven neighborhood.

As it does, Lee is taking stock of the moments that make a life—and inviting her viewer to do so, too. She’s in good company: fellow exhibitions include Jillian Shea’s A Rare Look From Some Old Red Oak; Danielle Giroux’s If the blocked artist were free, would the world breathe easier?; a collection of work titled Untitled, India from the multimedia artist Vani Bhushan, and a sweeping group show that pays homage to artists who have called the building home at various points in their careers.

“I just capture moments around me,” Lee said on a recent walkthrough of the exhibition, standing in front of her piece “Doll Cage,” from the series Re-Portal. “Here, these are all my self portraits. That’s how I understand the world. They’re really similar to prayers for me.”

Prayers, yes, and also meditations. In “Doll Cage,” which Lee assembled in 2017, stuffed, child-like figures pop out from every direction, an island of misfit toys entirely of the artist’s own making. On the bottom racks, there’s a pillow with a huge, calm face, a downtrodden-looking unicorn, a bare spool of thread, pulled in at the middle like a corseted waist. Across from it, a woman appears to have sprouted rust-colored butterfly wings on the wide, uneven and pillow-like left side of her body.

Many of them hang between the tiers of this cage, their heads, necks and feet stuffed into the holes on the structure’s shelves. Somehow, though, none of them seem quite trapped, so much as curiously exploring their surroundings. In part, that’s owing to the piece’s whimsical inspiration: Lee used to sew small dolls for her son to play with when he was a baby, just as her mother had for her and her sisters. Fifteen years after his birth, she’s still doing it as a kind of ritual practice.

“It became art later,” she said of the dolls with a soft smile. When he was still young, her son, Leehahn, helped her paint several of the pieces with watercolor paints that blurred, bled and expanded on fabric in just the right ways. For her, it became part of the piece’s inextricable tie to memory, as did the structure itself. Before she owned it, the “cage”—an old pipette holder—belonged to her beloved neighbor Andy DePino, who used it as a cookie rack. DePino died earlier this year.

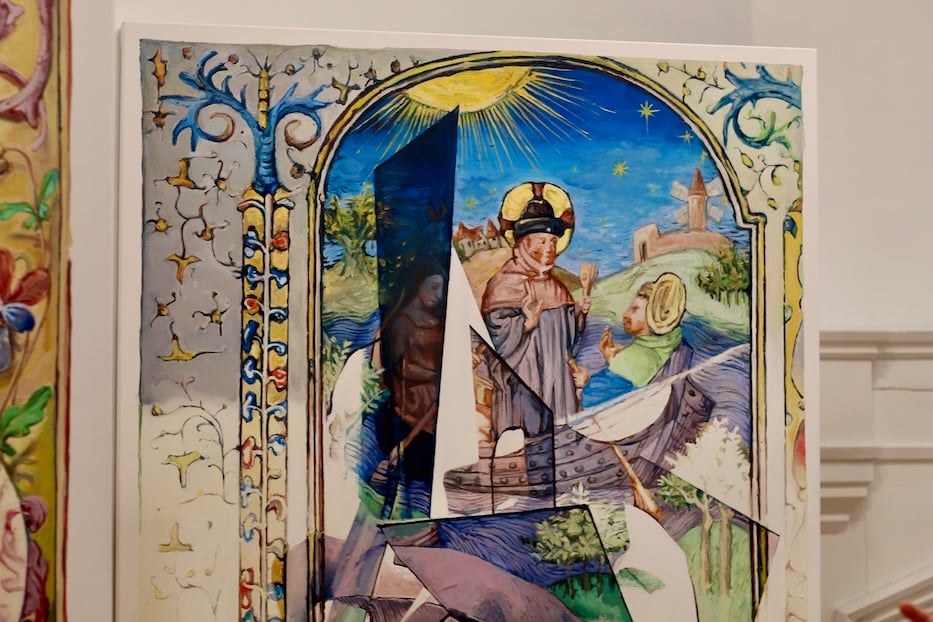

That sense of multiple generations, layered into a single piece or pieces, moves through the show, from a series of large-format, magnified “Doll Cage” photographs to a room filled with lush, richly decorated canvases inspired by the Spinola Book of Hours. In the latter, Lee has taken divine scenes and symbols from the book—which has its own roots in Christian 16th-century Belgium—and recreated them in vignettes that seem to shift and slice through space.

Initially, the series helped Lee reckon with her own sense of time five years ago, when the Covid-19 pandemic first hit New Haven. Working for hours in her Erector Square studio, and forced to stay at home because of lockdowns, Lee started asking herself “what did a day in the life look like,” she said. She thought back not just to the Spinola Book of Hours, but to manuscripts she pored over years ago at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

As she listened to other people mourn the new world in which they were living—which often separated families across the distance, and left people feeling increasingly isolated—she wondered how much of her own experience had actually changed. Lee is an immigrant from South Korea, meaning that much of her family is hundreds of miles away most of the time.

“When the pandemic hit, I felt like, I’ve just been living this life forever,” she said. Working in fastidious detail, she illustrated scenes from the manuscript, from stars twinkling against that Renaissance-blue night sky to trees, churning water, saints in bright, gilded haloes, and several small, exotic birds. On these, even the tailfeathers are treated with the utmost care, inviting a viewer to come as close as they can without actually touching the piece.

Behind the pieces, Lee has left another artistic Easter egg: a set of hinges that holds each panel to the wall, as if these wood frames are actually giant books. They work seamlessly with her “Pinwheel,” a sort of oil-on-canvas labyrinth in which she has pictured her home worktable, folded in portraits and memories from her own life, and added a blocky, geometric spiral that is so very her. When Lee installed it in the space, she placed it on a pedestal, with a black square in the center that is meant to draw a viewer in, and then invite them to look outward.

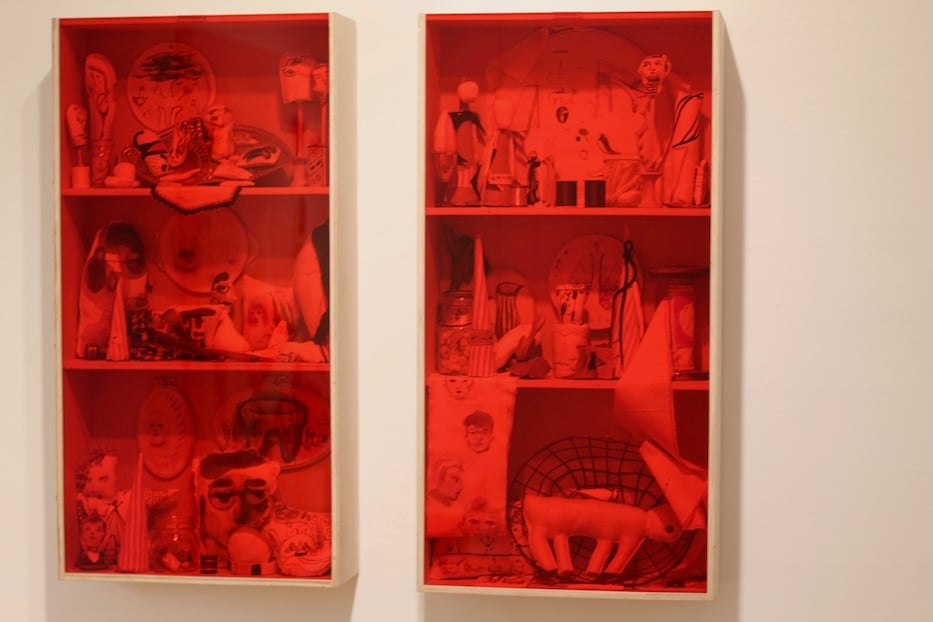

If the works marry process and memory-making (and motherhood on multiple levels, with a kind a gestation and birth that is clear in each), that carries through to a final room, in which Lee has installed several of her doll shelves and memory boxes alongside her canvas “Creases of Contemplation 깊은 생각의 주름.” As she took in the piece anew, she explained that the boxes are inspired by the glossy red paint that adorn her mother’s kitchen cabinets.

A detail of Lee's Creases of Contemplation 깊은 생각의 주름.

Throughout, these works meet the moment, leaving a trail of memory that is now part of the Ely Center’s legacy, even and maybe especially as the building prepares to change hands. Initially constructed as a private residence in 1901, the Trumbull Street mansion was for years the home of John Slade Ely and Grace Taylor Ely, the first of whom died very young in 1906.

Grace Ely lived another five decades, during which she developed a passion for the visual arts and the people who practiced them. Before she died in 1959, she drew up plans for the Grace Ely Trust, which honored her wishes for the space to become an incubator and a haven for artists in perpetuity. For years, it was, first with a show from the New Haven Paint & Clay Club in 1961 and then with dozens of exhibitions and collaborations that followed.

Then in 2015, the house—which was falling into disarray and struggling to keep up with the costs of maintaining an old building—announced it was closing its doors. By then, Wells Fargo managed the Grace Ely Trust, and all of the original trustees had died. It seemed like the end of an era, until Area Cooperative Educational Services Corporation (ACES), which runs the Audubon Street high school Educational Center for the Arts (ECA), bought the building (read about that in the New Haven Independent here) for under $400,000 (a decade later, it has gone for a little more than three times that).

When ACES bought the building in 2016, the nonprofit Friends of John Slade Ely House kept exhibitions running there, as ACES assessed the building’s structural needs and the changes that it would have to make before students could reliably use the space for their classes. And for a few years, it seemed like artists had reached an equilibrium on Trumbull Street. Then in 2022, ACES announced that it was selling the building.

In a kind of miraculous hail mary, Friends of John Slade Ely House was able to buy back the building for nearly $1 million—but not without strings attached. The $800,000 that the organization spent at the time was part of a loan from brothers and business partners Carmine and Vincenzo Capasso, who reserved the right to end the loan. They did so in early 2024, buying the building back in April of that year for $1.2 million.

After a long search, Director Aimée Burg said, the organization settled on CitySeed, a former warehouse where artists will continue the center’s new Keyhole Residency and hold exhibitions several times a year. The center plans to rent the entire first floor of the building—where the pizza-themed play Family Business was earlier this year—for $2,500 per month. You can read more about that in the New Haven Independent here and here.

On the cusp of those changes, it is a building where the walls teem with memory, from the cracking paint, leaky roof and perennial scaffolding to sunlight that falls in long, warm rays across the floor. In the past decade and a half alone, it has seen shows turning trash into treasure, celebrations of artists like Imna Arroyo, Linda Lindroth and the late Levni Sinanoğlu, artists fundraising for cancer research, and of course, a continued outpouring of work from the New Haven Paint & Clay Club.

There are shows welcoming back the world after near-closure, shows in which artists have declared, boldly and en masse across media, that dissent is patriotic, Nasty Women’s second annual show in 2018, and a celebration of the watershed book Our Bodies, Ourselves a year later. At the same time, it’s also been a site of trauma and discord, with a recent staff resignation and call for board turnover that took over a year to happen.

And of course, there are artists saying goodbye in a myriad of ways. Downstairs, the group exhibition Unfolding Between Walls becomes a poetic adieu (or for many of these artists, just an à bientot), with work that jumps from Shaunda Holloway’s shimmering monotypes on paper to book art from Christian Crowley and sculpture from Linda Mickens.

Upstairs, Bhushan’s work challenges the very nature of memory and witness itself, with photographs that recreate pivotal moments of truth-telling and simultaneous censorship in her home of New Delhi, India. Tucked away to the side, Kristin Eno’s Materials Kitchen suggests a bright future for the artists and educators using the space, who will continue their work long after the doors have closed.

Burg, who has served as the Ely Center’s director since 2023, said she is excited for the move to Fair Haven. Since ECoCA announced the transition earlier this year, she’s heard “a lot of positive feedback” from artists and New Haveners more broadly, particularly those hungry for an exhibition space in Fair Haven.

“It’s really nice that people want us there,” she said.

Read the Arts Paper’s coverage of previous exhibitions at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art here.