Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School | Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | The Hill

Tavares Bussey: “When I tell you, I am excited to get up in the morning and come to work, because I get to have a hands-on impact on the thing that gets them [students] up in the morning. That makes them want to be creative." Lucy Gellman Photo.

Cyanotype exposures in science class. Dance as a way to crack algebra equations. Painting and sculpture in social studies, so a land mass becomes more than a concept on a map. Theater and spoken word as a pathway into world languages.

Those are just some of the ways that Tavares Bussey, the new arts coordinator at Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School (BRAMS), envisions folding arts education into curricular development as he begins his first year at the Kimberly Avenue public school. A published poet, spoken word artist, longtime educator and self-described “micro-influencer,” Bussey sees it as giving back to a community that has nurtured him for years.

He takes over for Sylvia “Ms. Pet” Petriccione, who retired last summer after 23 years at Betsy Ross, and almost four decades working for the district. Later this fall, the school plans to dedicate its auditorium to her in gratitude.

"I didn't know a role like this existed," Bussey said in a recent interview at BRAMS, in an office tucked off the school’s first floor hallway. "When this position opened up, it married everything that I love about the arts [and administration].

“When I tell you, I am excited to get up in the morning and come to work, because I get to have a hands-on impact on the thing that gets them [students] up in the morning. That makes them want to be creative. And to be a co-laborer with my colleagues, to support these dreams coming true—I don't think you can beat that, honestly."

Dancers at BRAMS last spring, during rehearsal for an end-of-year dance showcase. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

Bussey's love for both education and the arts reaches back to his childhood in Edgefield, South Carolina, a small, rural town that is historically known as the birthplace of segregationist Strom Thurmond. Growing up, Bussey was surrounded by educators, including his aunts and great aunts. As an only child, he fell in love with dance, music, and theater, using it to entertain himself at home and at school. His mother, who later went back to school, put her own education on hold to raise him.

Despite a town that clung to its segregationist mythology—including a high school that to this day is named after Thurmond— "I was very fortunate," Bussey said. He had Black teachers from kindergarten all the way through high school. His uncle was the town’s sheriff. In and outside of school, he had a support system pushing him to excel.

"Even though we had issues, I saw success," he said. "So for me, what I'm doing is expected. And I want to show that to other kids."

He credits the arts with a significant part of that growth. When Bussey was in middle school, he discovered poetry through the words of Maya Angelou, while listening to a community member perform “Phenomenal Woman” over and over again. By high school, he had joined the school’s gifted and talented choir and show choir, where he was able to build up his confidence. When he wasn’t singing, he was excelling in his classes, ultimately motivated by the work of his teachers to become an educator himself.

It led him to his undergraduate work at Clemson University, where he pursued a degree in elementary education and also jumped into creative writing. After a professor introduced him to Toni Morrison's Beloved, he began writing poetry—and didn’t stop. He found that the art form, just like theater and voice before it, unlocked in him something that he couldn’t access any other way. Years later, it would earn him the sobriquet “The King of Vulnerability.”

BRAMS strings students performing at BLOOM in June. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

"I often give poetry credit for saving my life," he said. "Poetry has a way of engaging emotions, helping you navigate through those emotions, helping you convey those emotions without being raw and stripped, but while being able to be vulnerable. It shifted my trajectory in terms of the joy and how I honed my skills."

His journey as a poet took off alongside his path to education. As he continued writing, Bussey's list of role models grew to include Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, Langston Hughes, Nikki Giovanni and James Baldwin (he has the recording of Giovanni's interview with Baldwin saved to his computer, so he can watch it whenever he wants to), as well as the contemporary voices of Kendrick Lemar, Warsan Shire, Sonia Sanchez, and Suheir Hammad.

At the same time, he was building his love for education. After finishing his studies at Clemson, Bussey taught elementary school in South Carolina for close to 10 years, then moved to Connecticut to pursue a graduate degree in education at Post University. The East Coast was a culture shock, he said—Connecticut’s cities were much more diverse than what he had grown up with—but it was also a place he fell in love with.

In 201o, Bussey began working in New Haven's public schools, part of a wave of teachers trying to turn schools around as they struggled to keep up with their statewide counterparts. After teaching third graders at Brennan-Rogers Magnet School, he switched to middle school students with the goal of becoming a math coach. Meanwhile, he continued to grow as a writer, publishing his first book of poetry soon thereafter.

Baila Con Gusto CT's Amanda Duvall and Jason Ramos with BRAMS Students Rhyon Christie and Edward Mathews, and rhythm tap dancer Alexis Robbins at a "Rhythm Exchange" from the International Festival of Arts & Ideas earlier this fall. One of Bussey's initiatives is getting students out into the community more. Tavares Bussey Photo.

He never intended to become an administrator, he said. Then in 2014, the University of Connecticut opened its Administrator Preparation Program (UCAPP), and Bussey became its inaugural fellow. As a resident principal at Quinnipiac Real World Math STEM Magnet School, "I learned that I could be a different administrator," he said. He credited Grace Nathman, principal at Quinnipiac, as one of the mentors who helped pull him through. He also pointed to Marcella Monk-Flake and the late Lillie Perkins as mentors who helped transform his career, he said.

Bussey's search for an administrative position temporarily took him away from the New Haven Public Schools, first for an assistant principal position in Meriden, and then as the inaugural principal at Booker T. Washington Academy's new middle school in 2019. He was there when Covid-19 hit New Haven, and schools had to navigate the virtual pivot. He helped the school steer a cautious return to in-person education. By the time he finished the last school year, "I was worn all the way out," he said.

"I lost joy," he continued. "I lost all the joy. Burnout is real ... the work that happens there is good work, but it's a lot of work. And so I made the decision that I needed my joy. I feel like this is my calling, to be an educator, and I did not want to be in a place or in a space where I did not enjoy the work that I was called to do."

He knew he wanted to get back into the city's public schools. When he saw the position at Betsy Ross go up, he was amazed by how perfectly it fit his skill set.

In the school, his priorities include supporting students, teachers, and parents—while also acknowledging that they are navigating a new normal—and creating what he called "a cohesive vision around arts." For years, BRAMS has focused on the fine, performing and digital arts alongside core classes, so that they run parallel to each other.

"Not just painting and sculptures and photography," he said. "How can dance be incorporated in mathematics? How can acting and theater be incorporated in social studies? How does science utilize the arts? It's getting teachers to understand that it's not a heavy lift, because arts is in everything. It's everywhere."

"I don't want students to feel like they have to do a punch-in, punch-out type job," he continued. "I want them to do pretty much anything they put their mind to, including the thing that makes their heart sing. Whether it's dance, whether it's art, whether it's photography, whether it's acting. I want them to see opportunities open up for them where they can see real-time benefits to that."

To encourage school-wide involvement, Bussey has started a weekly newsletter with research from across the field, showing that arts education boosts overall academic performance and social engagement, relieves chronic stress and anxiety, and is often a critical tool for problem solving. This semester, he also started a teacher spotlight series, shouting out teachers who are knitting arts education into their practice.

On a recent Thursday, they included fifth grade social studies teacher Kelly Mikulski, who turned a unit on geographical land forms into a chance for hands-on visual arts learning. Pulling out clay, markers, old shoeboxes and flattened cardboard, she challenged her students to design their own country, from its flag to its terrain, climate, and size.

Students, in turn, got explosively creative: finished designs show aqua-blue bodies of water and dense forests, raised yellow rivers with windmill-shaped flag insignias, and a sign on a shoebox that reads "Pixie Hollow."

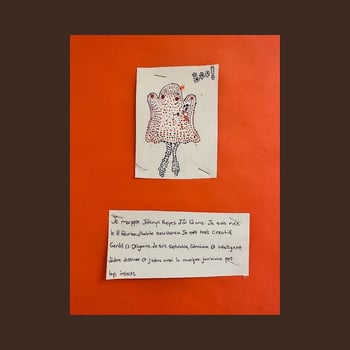

Other examples abound, Bussey said—he's never without his camera when he walks around the school. Earlier this month, sixth graders were learning about chromatography in science class, and used leaves collected around the school to document the process of separating out color. In a seventh grade French class three weeks ago, Bussey watched teacher Martha Combs guide her students through a lesson on pointillism. Once she had explained what it was, students made portraits alongside biographies written in elementary French.

In one, strings student Jolianys Reyes shows an oxblood-colored ghost, raising its blob-like arms as it daintily crosses its legs. In a text panel below, Reyes writes her name, birthday, and hometown of New Haven in French. Then she gets creative: I am very kind and diligent. I am helpful, generous, and intelligent. I love to make art and I also love music and I do not like insects.

In part, he said, he’s working to lift fellow educators up because he knows how hard their work is, he said. Currently, one of BRAMS' biggest challenges is recruiting students from outside of New Haven, which is baked into its DNA as a public magnet school. BRAMS has also not been immune to a district-wide (and national) teacher shortage: it currently has two vacancies, both in English Language Arts. Principal Jennifer Jenkins confirmed Friday that total enrollment is about 350 students at this time.

"Trying to figure out how we can support them in a world that shifted before our very eyes," he said. "In real time. There's a new normal that we have to be able to acknowledge. But in that new normal, there are ways ... there's a resiliency that we all possess. And if we tap into that resiliency, there are answers.”

In a phone call Friday morning, Jenkins said that she is thrilled to have Bussey joining the BRAMS family this year, with a skill set that marries artistry, teaching, social media and administration. She noted that middle school, particularly with BRAMS’ focus on the arts, is its own specific learning environment, and Bussey was the right fit for the job. Petriccione is not replaceable, she added: BRAMS isn’t changing the arts core that she nurtured for over two decades. "We want to keep her legacy alive," she said.

Instead, the school is working to grow it as it moves into a new normal. Jenkins said she’s been particularly impressed watching Bussey give teachers space to shine and take the lead. Prior to his appointment, she remembered asking herself: “What does the school need in this moment?” He stood out because of the balance of teaching and administrative experience, particulary in a middle school setting, that he could bring to the role.

“I’m very glad we were able to bring him onboard,” she said. “Everything else was in place—the way the program was set up, we’re not changing anything. But wherever we can enhance it, wherever we can grow, we will.”