Public art | Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Ninth Square | Skateboarding | Arts & Anti-racism

14-year-old Justus Graham (in green and white cap) was one of dozens of skateboarders who came to Friday's launch. Lucy Gellman Photos.

In a George Street parking lot, 14-year-old Justus Graham balanced his skateboard on the lip of a new skate bowl that had traveled 300 miles to get to New Haven. A live bass guitar thrummed around him. He pressed his left foot forward, focused on the curve, and was suddenly in motion.

Three blocks away on Crown Street, Elida Paiz Pineda ducked beneath a doorway and watched as a film flickered to life. Seashells stretched across an open beach. Sunlight scattered through trees in Edgewood Park. A Bridgeport street revealed itself one step at a time. This was the artist’s world, upturned in a pandemic.

Those two scenes took place just blocks away from each other Friday night, as Artspace New Haven launched its 2021 Open Source Festival, a reimagined version of City Wide Open Studios that stretches across two weekends this month. Friday night, artists and skaters alike fêted the arrival of a prefabricated skate park on George Street, as well as several outdoor films at Artspace’s Orange Street building.

The festival continues this weekend with open studios on Oct. 24 and 25.

Viewers watch Elida Piaz Pineda's film.

“For me it was a perfect example of young Black people in New Haven who were running small organizations, who were working as creative people—musicians and artists and writers—and had to create a world for themselves that incorporated their practices,” said Lisa Dent, executive director at Artspace New Haven. “I knew skateboarders to be visual artists, to be interested in performance, and to create and find ways to show each others' work.”

A Skate Bowl Takes Shape On George St.

Friday night, that shift began with a new skate bowl at Orange and George Streets, in a parking lot turned DIY space with merch booths, a painting pop-up, and a skateboard repair station on site. Up a sturdy wooden set of stairs that still smelled of sawdust and cedar, four dozen skaters gathered around the basin, watching as one or two dipped in at a time.

Every few seconds, a roar went up from those on deck, as skaters turned their boards vertical, and pounded them to the wood in a show of support. Push To Start NHV Founder Steve Roberts buzzed around, delivering praise through a bullhorn as his eyes gleamed. Below, someone had already tagged the bowl with scrawls of black graffiti.

The modular skate park, which first appeared at the Kennedy Center in 2015, is the brainchild of designer Ben Ashworth, himself a skateboarder and member of the D.C-based Workingman Collective. Earlier this month, it made the journey from Washington, D.C. to New Haven, where it was reassembled before last weekend’s raucous christening. It is a collaboration among Scantlebury Skate Park leaders Roberts and J. Joseph, the Kennedy Center’s Finding A Line initiative, and the City of New Haven. Roberts said that it will be there for a full year, waiting for skaters to make it their own.

“Honestly, it feels like the completion of something that I’ve had in my head for a while,” he said. He pointed to the number of unsanctioned space he and his board have recently gotten kicked out of, from Beinecke Plaza to the “tree bump” on Broadway where a hotdog place now stands. “I’m excited to do stuff like this. We’re constantly looking for new spots.”

Nearby, Graham found his place at the edge of the bowl, waiting to take another spin. A freshman in theater at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School, he is one of Roberts’ “Scantlebabies”—a skater who began with Push To Start NHV, and has been learning through near-daily practice at Scantlebury Park since it opened last year. For him, a wooden, wheeled board has become a lifeline during the pandemic.

In just 12 months, he said, skating has helped him ditch video games and screens, regulate his emotions, and learn to dust himself off and get back up when he falls. When the last school bell rings, he skateboards to Scantlebury Park, where he spends the next six to seven hours of his day. Only then, after dark, does he head to his home on Dickerman Street. A year in, he’s working to get his 10-year-old brother off video games and into the skatepark.

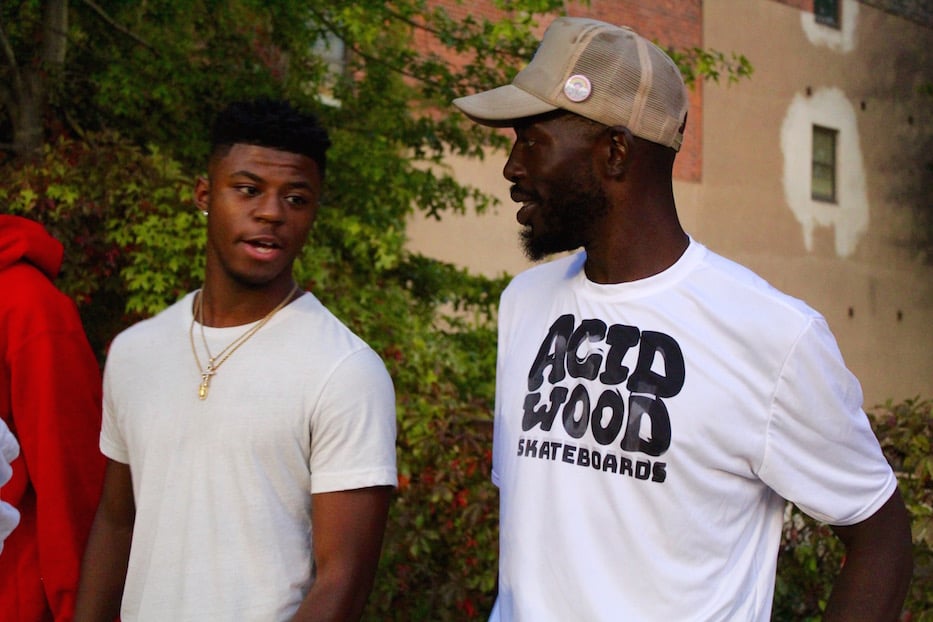

Top: Steve Roberts (in cap) Friday night. Bottom: Justus Graham takes the plunge.

“It’s the community,” he said. “There’s just a lot of really good people.”

Friday, Graham kept his eyes trained on the bowl’s C-shaped slope and curved bottom. He leaned his torso forward and waited for another skater to exit the bowl. As he left the ledge and began to accelerate, his green-and-white snapback transformed into a ribbon of green. Above him, 40 voices rooted him on, some yelling his name as others slammed their boards to the ground.

As dusk fell, U.S. Ambassador of Skateboarding Neftalie Williams made his way through knots of sweatshirts, baseball caps, newly-bruised knees and elbows, and well-loved boards to one side of the bowl, and then the other. A visiting fellow in race, culture and community at the Yale Schwarzman Center, Williams looks to skateboarding as bridge and catalyst for cross-cultural dialogue, an approach he has brought to a New England skate camp, work with Syrian refugees in the Netherlands, and most recently Scantlebury Park (read a story about that from the New Haven Independent's Maya McFadden here).

Every so often, he stopped to study skaters as they gathered speed and went airborne. He pointed to the way that skateboarders communicate with each other in a shorthand of locked eyes, nods, whoops, and pounding boards. Several pumped their arms, sending out clouds of sweat and body odor from their soaked shirts.

“This becomes a space where we develop a language on how to be together,” Williams said, noting that for both new and experienced skaters, a new bowl levels the field. “Everybody is learning.”

Street Films Light Up Crown St. Gallery

Top: Artist Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez interviews dancer-turned-filmmaker Alexis Robbins. Bottom: Elida Paiz and Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez.

Top: Artist Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez interviews dancer-turned-filmmaker Alexis Robbins. Bottom: Elida Paiz and Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez.

Down Orange Street and onto Crown, artists and passers-by milled around Artspace’s street-facing windows, watching as light spilled onto the sidewalk from videos playing on loop. This summer and fall, Artspace commissioned work from cross-disciplinary artists Alexis Robbins, Elida Paiz Pineda, and Amira Brown. Viewers have a chance to weigh in, by making a short response video that Artspace will share to its website.

Artist Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez, who served as the project manager for the films, referred to the process as a “closed call”—an effort to diversify the artists working with the festival by reaching out to them directly. As attendees nibbled on tamales her family had dropped off at the event, she brought them over to watch the films, sometimes chatting with the artists as their work played a few feet away. On Orange Street, she spoke animatedly as Amira Brown’s cartoon film played behind her.

“We’re really acknowledging the work that artspace has to do with rebuilding its relationship with the community,” Gonzalez Hernandez said. “Any work has to reflect the people who are actually from here. This is where rebuilding starts.”

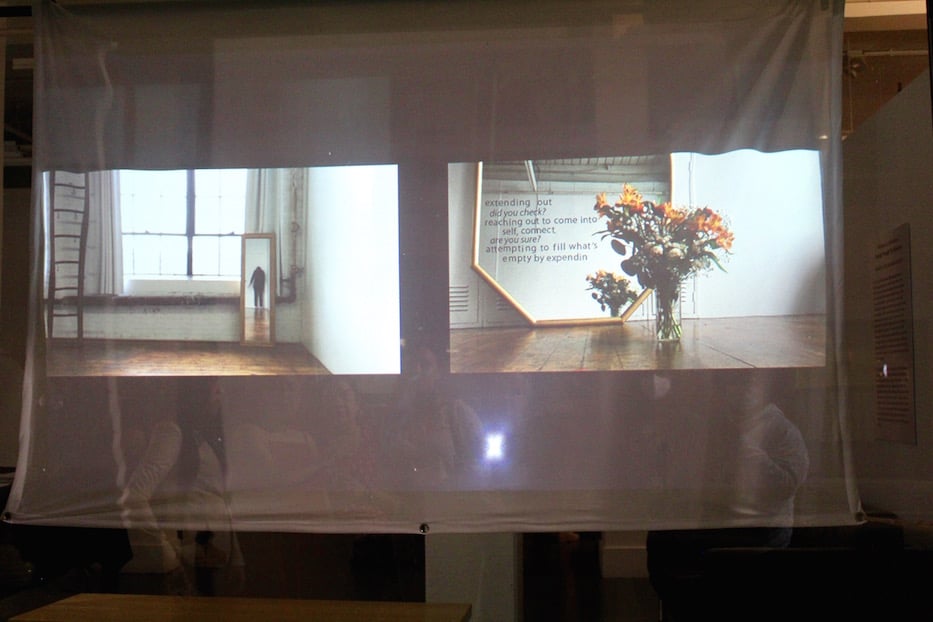

Top: Work by Alexis Robbins. Bottom: Paiz Pineda's film.

By a Crown Street doorway to the gallery, Paiz Pineda talked viewers through their film, Just at the Edge of Earth and Breath. Strips of sand and empty beach, scenes from Edgewood Park, and sections of their childhood street Bridgeport flashed up on the screen, poetry in white text below. A rose garden appeared, flowers gently swaying. Some lines—I wanna hold you—felt like Sappho’s fragments, yanked into the present day.

The film is a reflection on their year, they said. When Covid-19 hit last year, the artist was working in a grocery store, and contracted the virus. After lasting symptoms forced them to leave their job, they were unemployed from May to September 2020. During that time, they relied on mutual aid, including the New Haven Pride Center’s food distribution program. They got involved in support work in their own neighborhood. They lost family members. The world, impossibly, kept going.

“Grief is just love with nowhere to go, right?” they said beneath the covered alcove where the film is based. “I chose this space because it reminded me of seeking shelter.”

Dent said the Open Source launch, which kicked off two weekends of open studios across the city, is part of a wider reimagining of the years-running fall festival. This year, she said, she looked at ways to engage artists and viewers while still in the midst of the pandemic, make it financially sustainable for the organization, and “create a moment of engagement that was also healthy for my staff.” After a year braving the virtual pivot in 2020, four weeks of open studios became two. There are still online events for viewers who wish to engage that way.