East Rock | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | City Gallery | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

Nathaniel Donnett, In a subtle but noticeable change, the pattern is transposed a step higher. Lucy Gellman Photos with City Gallery's permission.

The shoelaces hang in a thicket of bright white, metal eyelets shining at their ends. A section of brick wall, stacked with empty boxes and a humming AC unit, looks out from a paper fan. In the lower left of the installation, a photograph of Jessica Krug, a white woman who posed as an Afro-Latina until 2020, appears on screen momentarily. It is replaced by Henry Ossawa Tanner’s The Banjo Lesson.

“Aesthetics synthesize the object,” announces a steady voice, coming in over pulsing, old school beats.

Nathaniel Donnett’s installation is part of Legacy and Rupture, a group show running at City Gallery through May 30. Curated by New Haven-based artist Howard El-Yasin, the exhibition features multimedia work from Donnett, Sika Foyer, Merik Goma, Ari Montford, Ransome, and Marissa Williamson. Together, it is a sweeping and polyphonic look at Blackness, artistry, and the legacies of forced migration and displacement.

The show is the first time that all seven artists, who usually work individually, are exhibiting work together. The gallery is open Friday through Sunday at 994 State St. More information is available here.

Detail, Sika Foyer’s Trickster. Merik Goma's work is pictured in the background.

From its outset, Legacy and Rupture probes the limits of the very words on which it is based. When he was curating the show, El-Yasin was particularly informed by the work of writer, professor and Black scholar Christina Sharpe, in which she sees the past as coming up to fracture or “rupture” the present. In her critical framing, the past is not a cemented, immovable artifact at all, but that which lives on as a haunting, pulsing and sometimes ruinous presence.

Sharpe’s framing applies specifically to Blackness, and specifically “living Blackness” in the long and enduring history of forced displacement, enslavement, Jim Crow, and centuries of economic disenfranchisement and erasure of Black people. Or as she writes in In The Wake: On Blackness and Being: “The past that is not past reappears, always, to rupture the present.”

“I was thinking about rupture in a global way, as well as a culturally specific context,” El-Yasin said in a phone call Friday night. “And so the show itself really crosses those boundaries. I'm not interested in something that's monolithic. I'm interested in talking about the ways that Black artists are working in the contemporary moment.”

Inside the State Street gallery, he has transformed the space into a sort of multi-installation installation, where works speak to each other in sharp, sometimes hushed and rapid tones from the walls, the corners, floor and street-facing windows. The gallery’s square footage works to his advantage in this way: it is nearly impossible to look at one piece without the physical intervention of another. The result is a sense not only of intimacy with the works, but a sense of their interrelatedness.

In the center of the gallery, Foyer’s Trickster occupies the space, its swaths of multicolored yarn catching in the light. In her practice, the artist builds on both oral and visual legacies, using rite, ritual and folkloric tradition to bring the past directly into her present. She employs the Trickster trope, which appears in but is not limited to African literary and oral tradition. There’s a duality there that El-Yasin loves, he said: the Trickster can switch on its listener (or in this case, viewer) at any time. There’s a non-binary quality to it that fits the heft of the piece, which also works outside of a Western or Eurocentric vocabulary.

Detail, Trickster. Marisa Williamson’s series Monuments To Escape and Kamar Thomas’ Veil. is pictured in the background.

Trickster, which is suspended from the ceiling, reveals its layers the longer a viewer looks. Foyer has wrapped soft yarn, printed fabric and stiff, thick wool around a large skeleton frame, in a process that asks a viewer to look closely. There’s a demand there, for her viewer to spend time with their past and explore what they see. It also feels like a reclamation—the Massachusetts and New York-based artist is putting her hands back into a wrapping tradition from which she was historically stripped.

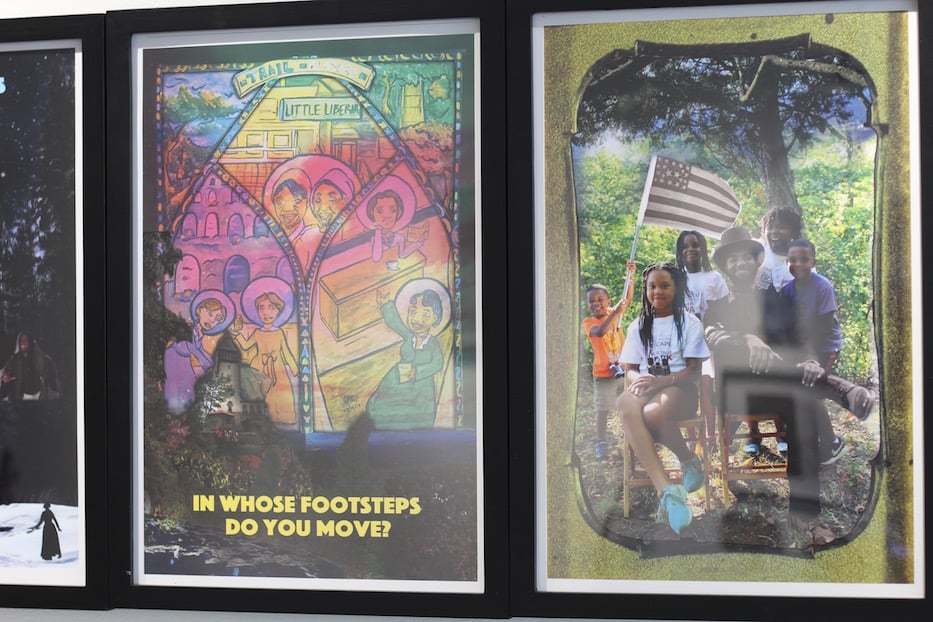

Around it, pieces spring to life from the walls. On one side of the gallery, Marisa Williamson’s series Monuments To Escape reimagines the New England landscape with reworked, often witty prints that are replicated as postcards below. In each, she has started with a sentimentality-drenched graphic—think the National Parks posters during the Works Progress Administration—and flipped the script. In one, she has depicted the oft-forgotten Freeman sisters of Bridgeport with an animated, haloed group of women, lifting their arms over the phrase “In Whose Footsteps Do You Move?”

In another, she has recreated a portrait of the Black photographer Augustus Washington, whose Hartford-based photography studio was born in 1846 in an effort to raise money for college. Washington, who photographed the famed abolitionist John Brown, was largely forgotten by state and national history and “left no portrait of himself.” Williamson gives that legacy back to him, depicting the photographer in sepia tones among smiling Black kids on the New England trail.

Detail, Monuments To Escape.

There’s also pain and frustration there—Washington was practicing photography at a time when Louis Agassiz was using the same technology to document enslaved Black people in the American South. Agassiz, whose images were pseudo-scientific and often dehumanizing, is still taught in art history classes across the country. Washington, whose portraits are stately and dignified, is not. Within the state, where the tourism industry has banked for years on white nostalgia, he’s not a household name.

It’s a reminder that the gallery and the surrounding East Rock neighborhood—itself a very white space, although the show is not—sits on land once stewarded by the Quinnipiac, Wappinger and Paugussett Tribal Nations, in a state where slavery was legal through 1848. So too Ari Montford’s Indigenous Trauma, a series of wrapped arrows that are embedded in the gallery’s walls.

El-Yasin has used the space to install the piece across the gallery, such that the arrows form a line to each other through Trickster. In turn the artist, who is Black and Mashantucket Pequot, explodes and challenges stereotypes of American Indians in visual culture. As works of art, the arrows carry questions around craft, authorship, and who has been allowed historically to wound and be wounded. As they protrude from the walls, the arrows also give the show a sense of physical propulsion, as if it is moving toward an inflection point at all times.

Like all of the works in the show, it operates outside of and even in opposition to a Western, settler colonial framing. El-Yasin said that’s part of the point.

“I was more interested in artists who were speaking to me as a Black person,” he said. “I'm not interested in a white audience. I'm not apologizing for that. Even though it's in a white space, it's not supposed to speak a language that is for that audience.”

Detail, Coming Out and Indigenous Trauma.

Throughout, there’s a pulsing reminder of how recent and alive the past still is. In Donnett’s In a subtle but noticeable change, the pattern is transposed a step higher, the artist yokes Black American past and present, bringing one bubbling up through the other. The title is a reference to Miles Davis’ 1959 “So What?,” a nod to modal jazz that seems to extend to the format and depth of the installation itself.

From a video on loop, an even voice coasts over images of paintings, old and contemporary photographs, video footage, and signs for political candidates, keeping time with a beat underneath. Two framed are installed hang above, inviting a viewer to explore their layers of plastic straw, paper, painted tape. A copy of Margo Natalie Crawford’s Black Post-Blackness hangs upside down in an oversized Ziploc bag. Beneath it, tilted against the wall as if it has been forgotten, is a photograph of two sno-cones shining in the sun. Both—one red and one blue—pop from their bright white styrofoam cups, as if the whole thing is a jumbled American flag.

Other works probe the multiple intersections at which these artists may live. Ransome’s Coming Out, which depicts two Black, gay lovers who are enslaved, does a sort of past-present-future visioning in which El-Yasin is still finding nuance and meaning. In the work, a mix of acrylic painting and collage, two men lie back-to-back, their faces away from each other. Their skin is a blue-black that almost matches a swirl of night around them.

Dressed in bright shirts, they sleep beneath a quilt patterned with geometric star variations, blue and tan at the centers. It evokes the work of quilters at Gee’s Bend, Alabama, where a small group of women has made the art of quiltmaking into their legacy and economic lifeblood.

El-Yasin said he was also excited by the amount of magical realism—and untold history—packed into the piece. Recently, he’s been thinking about the erasure of Bayard Rustin from the mainstream history of Civil Rights.

“I’m still astonished by the idea, the possibility that some of my ancestors could have been gay,” he said.

Merik Goma's Your Absence Is My Monument. Top photo by Lucy Gellman; bottom courtesy of City Gallery.

Goma’s Your Absence Is My Monument brings together two and three dimensional worlds, recreating in an installation the same space that is captured in a dramatic photograph. In both, a viewer sees a space that is filled with signs of former life—an uncovered mattress, pages of a book, a naked lightbulb on the wall.

In the photograph, a figure stands in the space, inspecting it. He wears a suit and tie, a long jacket, as if someone has sent him here from an office to inspect the absence. In the installation, the viewer has the opportunity to be that person—or to consider whether they have a right to be there at all. There is something intimate and staged, curated and human about the setup, which doubles as an invitation to look more critically at how we treat shelter as a luxury rather than a right.

For its heft, Legacy and Rupture is also a hopeful show. Beside the front door, Kamar Thomas’ Veil shows a figure looking out over a mask, their face largely obscured by a veil of red, pink and yellow roses. Their skin is blue, brows furrowed, as if they are waiting.

For what, or whom, it isn’t entirely clear.

Detail, Kamar Thomas’ Veil.

City Gallery is open Friday through Sunday 1-4 p.m. or by appointment. Legacy & Rupture runs through the end of May. Read more about the show here.