Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | Elicker Administration

Roberts, at center. Nia Riles-Mathis and Hyclis Williams are on either side of him. Lucy Gellman Photos.

How would Steve Roberts spend nearly $85 million in federal aid?

Grow youth programs. Paint murals and fire hydrants. Build skate ramps. And launch year-round projects that give young people ownership of the city—and pay them for their work.

Roberts, who leads the youth skateboarding program Push To Start, pitched that idea Wednesday evening at Civic Space, a new initiative from the city to get public input on how to spend a portion of the American Rescue Plan. For two hours, he joined nearly 60 New Haveners and several city officials in the basement of the Ives Main Library to discuss, debate, and think through what city residents would like to see.

Civic Space is dedicated to an $84.2 million tranche of money coming to New Haven, the second that the city will receive from the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan. The city’s Board of Alders has already passed a spending plan for an initial $26.3 million. In all, the dollars amount to $110.5 million.

“This American Rescue Plan funding is an opportunity for us to think about how we want to invest,” said Mayor Justin Elicker, adding that he feels hopeful as the city recovers from and looks beyond the pandemic. “This is a time to think big.”

Wednesday, the group that came out included teacher and parent advocates, educators, small business owners, immigrants, law students, and organizers from Black Lives Matter New Haven and the Connecticut Bail Fund. The session, the second of five, follows a similar one at James Hillhouse High School last month.

Future sessions are planned for July 8, August 3 and August 17 at branches of the New Haven Free Public Library and the Shubert Theater. More information on dates and locations is at the bottom of this article.

Click here, here, and here to read previous articles about how Covid-era federal aid is slated to be spent in New Haven. Click here to apply for arts funding that the city has created from that first $26.3 million chunk.

The Importance Of Feeling Heard

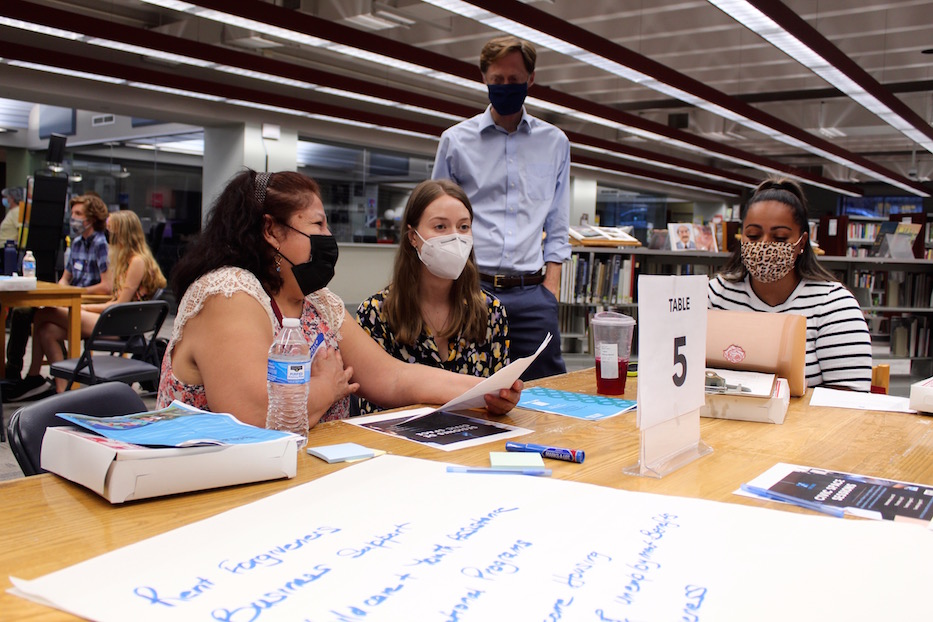

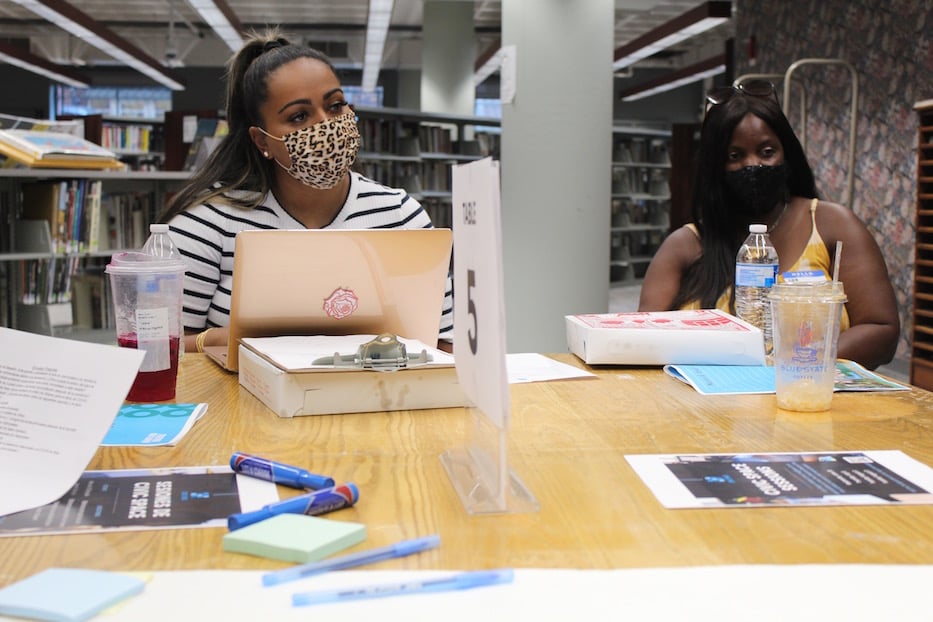

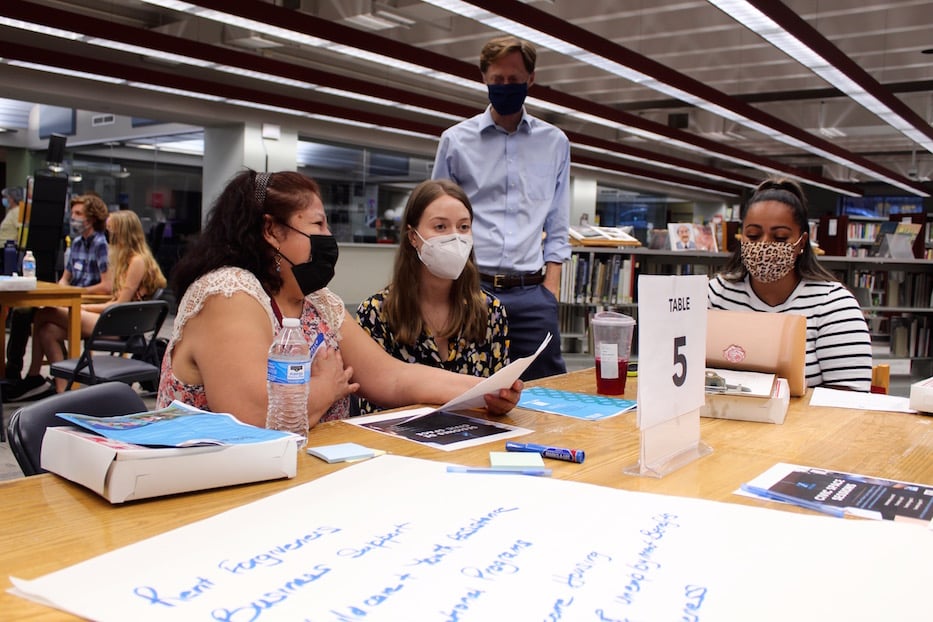

Corinna Santos and Nia Riles-Mathis.

At a table on the far side of the library’s basement, five New Haveners gathered around Corinna Santos, who is the program manager and liaison for the Civic Space initiative.

Santos asked participants what they saw as the “biggest persistent challenge” to themselves, their families, and their neighborhoods during Covid-19.

Hyclis Williams, the president of New Haven’s paraprofessionals union, sat up a little straighter in her chair. As a para and teacher advocate and parent of three New Haven Public Schools graduates, she looked immediately to the lack of summer and year-round programs for young people.

In particular, she said, the city doesn’t provide many job opportunities for young people between the ages of 16 and 25. When she looked at summer programs this year, she realized that many of them were cut off at 15 years of age. She said she wonders if more job opportunities for youth would stem the recent rise in citywide violence.

“That’s the age that is more difficult to manage, when they get to that age,” she said. “They kind of want to do their own thing. It’s hard to get them to see what you’re seeing or to conform with a lot of things, now that they want to break out and do their own things.”

Hyclis Williams: "A lot of people don’t get heard at all."

Roberts agreed. As a kid growing up in the city’s Newhallville neighborhood, 13 or 14 was the age at which he started skateboarding. Without programs like the one he runs now, “I was running around downtown, trying to find my own way,” he said. Then his basketball coach, educator Kermit Carolina, connected him with hands-on summer jobs offered by the city’s Youth @ Work program. Carolina is the supervisor of youth development and engagement for New Haven Public Schools.

Roberts landed one painting fire hydrants when he was 14. Youth in the program rode around the city with members of the New Haven Fire Department, painting hydrants that spanned New Haven’s 18.7 square miles. Roberts said it made him feel like the city belonged to him. It also made him wish that Youth @ Work had the capacity to take on more people, with better pay, for longer periods of time.

“It was like, every time I’d go past a fire hydrant—”

“I painted that,” Santos finished his sentence to chuckles from the table.

“Yeah!” he said. “I was proud of it. And a lot of times, that’s a problem. Like, a kid, where they’re at that age where they’re too young to be involved with what’s going on downtown, but they still have the strength and know-how to know what’s going on. And for someone who wants to get involved with their city, it’s kind of like a glass ceiling.”

Roberts pointed to the lack of paid opportunities for young people that the city offers. He sees the two student positions at the city’s Board of Education as largely ceremonial, particularly because the members cannot vote. He looked around the room and noted the absence of young people at the event.

He said that when youth feel like they have a stake in something—whether it’s a Black Lives Matter mural or a budding skate park—they are more likely to care for their neighborhoods and their city. After he started skating in Edgewood Park, he was more likely to throw away his trash and de-litter the space.

“That’s really the main issue,” he said later. “Somebody who’s poor, who comes from an underserved neighborhood, doesn’t really have that sense of ownership. There are kids who sell candy in school. Kids who get in trouble for graffitiing on desks. Kids who are truant because they have the energy and need somewhere to direct it. Take those kids, who have artistic talent … we just want to redirect it.”

Lucila Díaz, Carmen Hatchell, Mayor Justin Elicker, Corinna Santos.

Williams jumped back in. Living in the city’s Edgewood neighborhood, she sees that when the city wants something from its residents—higher vaccination rates, or votes during an election season, for instance—elected officials make time to go door to door and talk with residents. She wondered aloud what it would look like for New Haven to have that kind of human infrastructure all the time.

“Go out in the park where the youths are,” she said. “Go out there where it’s visible, where people meet. And talk to people! Walk around the streets. Walk around the common areas. The parking lots. Find those places … and share that we want to do this thing. Show some guidance.”

“Nobody ever addresses what they want, and what they’re thinking,” she added. She suggested that the city could work more closely with neighborhood leaders working at the grassroots, from educators to activists. She stressed the importance of meeting the youth where they are—including sending peer-to-peer support—instead of asking them to come downtown and sit in on meetings run by a largely white, older group of city officials.

“A lot of people don’t get heard at all,” she said. “They don’t know where to put their voices. They don’t get these emails that we get to come to this. And if they did even get it, they don’t feel like they would be heard.”

Lucila Díaz, a Mexican immigrant who now lives in the city’s Hill neighborhood, said that she feels many of those needs also apply to New Haven’s polyphonic immigrant communities, particularly those in which immigrants have limited English.

She hears from the city when it wants her car moved for street sweeping—not when it's interested in sweeping public input. While New Haven is a sanctuary city, it’s also unclear to her whether the city genuinely wants to hear from the immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers that now call New Haven home. She pointed to the lack of language access at the event, including languages other than Spanish.

“The immigrant community is so rich and they feel that they can never be heard,” she said, speaking in Spanish through translator Carmen Hatchell. “There needs to be more asking people from the government … that initiative to go to people.”

How To Prioritize The Funds

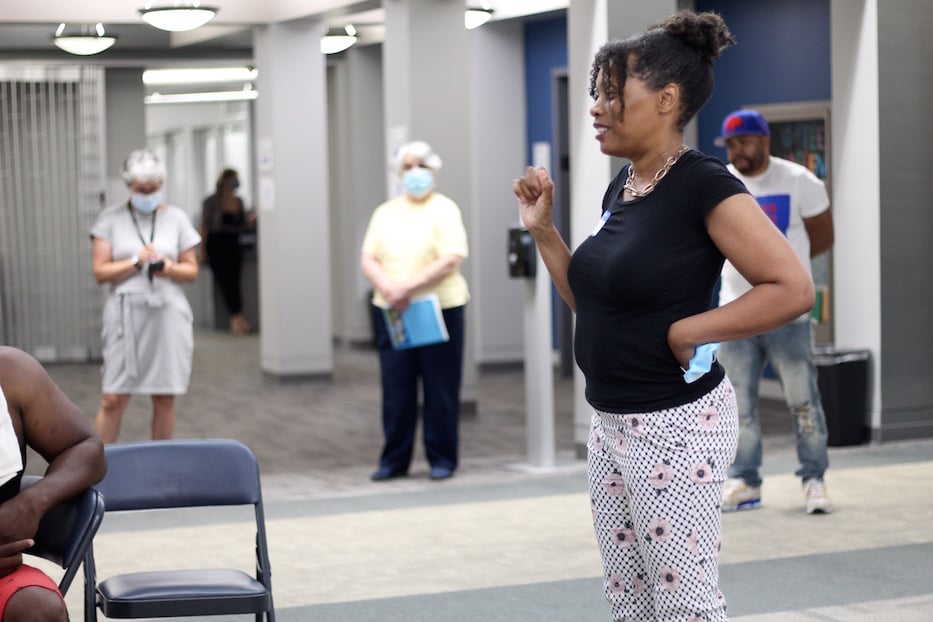

Marcella Monk Flake, who leads the Monk Youth Jazz and STEAM Collective, Inc.

Groups also discussed whether they would split funding evenly between designated areas of need, or prioritize some over others. Those included rent and loan forgiveness, small business support, childcare and youth assistance, educational programming, low-income housing, and unemployment benefits.

In Santos’ group, the answer came back to youth, as well as housing and infrastructure (“our roads are bad,” said Williams). As a parent, attendee Nia Riles-Mathis said she wanted to know that her kids were going back into safe schools that were fitted with up-to-date appliances and air filtration systems. Earlier this academic year, that preparedness was part of a fierce debate between parents and the city on whether and when to reopen schools.

Roberts advocated for more childcare and youth assistance, including the creation of electronic-free safe green spaces for young people to play and learn. Those programs already exist, he said—the city just needs to invest in them and has the chance to do it with federal dollars. He gave the example of a cooking program through which kids could learn math, or a fashion design program where they could pick up business skills. Williams added that the city no longer has a technical school.

“Everybody has something,” she said. “Everybody has something to give. Everybody has some good wits. You just have to tap into it, and let them be able to explore and learn. Sometimes people sing. Or they’re good at singing. Let’s tap into the youth and let them really be able to explore and expose themselves.”

Both he and Williams added that federal aid should not be distributed equally between neighborhoods. Newhallville, Dixwell, the Hill and Fair Haven need more help than East Rock and Wooster Square, for instance. Williams pointed to a decades-long pattern of redlining and resource scarcity that have made New Haven a city in contrasts.

Kerri Kelshall-Ward.

In a feedback session at the end of the evening, Civic Space participants from multiple groups said youth had been a focal point of their discussions. Marcella Monk Flake, who leads the Monk STEAM and Jazz Academy, said that she would love to see a revitalization of Yale’s Upward Bound program, of which she is a product.

Kerri Kelshall-Ward, the president of Financial Empowerment for Women, LLC, noted the need for financial literacy, job training, and college preparedness programs for young people.

“We need to invest early in our youth,” she said.

In addition, attendees pointed to the need for long-term funding for job training, environmental stewardship, teen recreation centers, affordable housing and accessible public restrooms.

The next three Civic Space sessions are scheduled for Thursday, July 8 at the Fair Haven Branch Library; Tuesday, August 3 at the Wilson Branch Library; and Tuesday, August 17 at the Shubert Theater. For more information, or to give input online, visit the program’s website.