Crafts | Fashion | Painting | Visual Arts | Woodbridge | Palestine Museum U.S. | Sculpture

The Art of the Palestinian Thobe runs through the end of this year. Pictured is a thobe from the collection of artist Renate Ghannam, who first encountered the garments through her husband's family. Lucy Gellman Photos.

It’s the sunflower- and seafoam-colored thread that pulls a viewer in, glowing gold against a thick black fabric backdrop. At the center of the chest, a deep V in the embroidery opens to a fiery inverted triangle, its sides fluttering out in a delicate couching stitch. Along the neckline and sleeves, thread twists and twirls into delicate patterns. Even on a mannequin, the thobe looks like it’s prepared to come to life, and begin moving gracefully through the space.

The piece is part of The Art of the Palestinian Thobe, one of two special exhibitions now on view at the Palestine Museum U.S. in Woodbridge. Installed across multiple galleries, the show asks a viewer to pause and look closely at the history of Palestinian embroidery, or taṭrīz, in a time of intense political turmoil and upheaval. A celebration of both craftsmanship and culture, it unfolds across multiple galleries and runs through the end of this year.

The other exhibition, The Art of Gaza, runs through Jan. 31 and showcases the work of several Palestinian artists, including those who are fearing for their lives in the ongoing Israel-Hamas war. Like much of the other work in the museum, its strength is in its asking the viewer not to look away, but to look closely, and consider the impact and trauma of forced migration and displacement on an artist’s life and work. More on that below.

"It's a very important aspect of Palestinian heritage and Palestinian culture," said museum founder and director, Faisal Saleh, on a recent tour of the thobe exhibition. "It’s a way Palestinian women have expressed themselves for centuries."

In the museum, a sanctuary for Palestinian arts and culture tucked away off the Litchfield Turnpike, the show grew out of a shared love and appreciation for craft, and the rich, layered stories that a single garment can tell. Months ago, the Bremen-born artist Renate Ghannam reached out to the museum with the news that she had several traditional thobes crafted and worn by her husband’s relatives. All of them come from Deir Dibwan, a Palestinian city that sits to the East of Ramallah.

Between the garments, they display a delicate cross-stitching, or taṭrīz, that is a trademark of Palestinian embroidery. Each has its own flair: there is a red and white thobe that sports delicate flower shapes along the chestpiece or qabbah, which is typically embroidered separately and then stitched onto the thobe before completion; a hand-stitched bedouin thobe with starburst patterns that explode into color across the chest; a green-and-black thobe that Ghannam can remember her sister-in-law wearing decades before it became part of the museum’s collection.

The black-and-gold thobe, a piece that Ghannam dates to the 1970s, offers viewers a glimpse into a couching stitch that is more common to artisans in Bethlehem and Ramallah. Installed closest to the museum’s low stage, it looks out onto the room as if the mannequin is about to start walking through the space, weaving through rows of chairs to books that are assembled in the back of the room. All are floor length with a sloping V at the neckline, in a traditional cut that reaches back to the first and second centuries.

Renate Ghannam's work in the show also includes painting.

“The reason why these dresses are very important to me is first of all, because these were family pieces,” Ghannam said during an exhibition opening earlier this fall. “I know exactly who made them, and when they approximately were made, and who wore those dresses.”

At the time, she added that there’s an element of cultural preservation: she’s noticed fewer and fewer Palestinian women and girls wearing the thobes over the years, as she and her husband return to Palestine to visit family members. Instead, she said, many opt for a modern, often lighter weight Abaya, or modest Islamic dress. “I do respect their choice of Islamic dress, but I also felt that part of the Palestinian heritage and Palestinian culture is embedded in these kinds of dresses,” she said.

Around the space, the garments both invite close looking, and enter into a dialogue with the multimedia work of several other artists. On a side and back wall of the gallery, a viewer comes face-to-face with a series of huge, vibrant photographs from the Austrian artist Tabea Marie Kerschbaumer, whose series 48 Stitches documents first- and second-generation Palestinian women who are living across the globe and in the diaspora. That includes in Germany, where she has done much of her work.

“The project is a celebration of the culture of Palestinian women and draws attention to the Middle East conflict through the stories of these women, reads an accompanying statement, and the result is as effective as it is affecting. Across the series, women have written their own narratives to accompany the photographs, with excerpts (read some of them here) that bring a viewer into their lives.

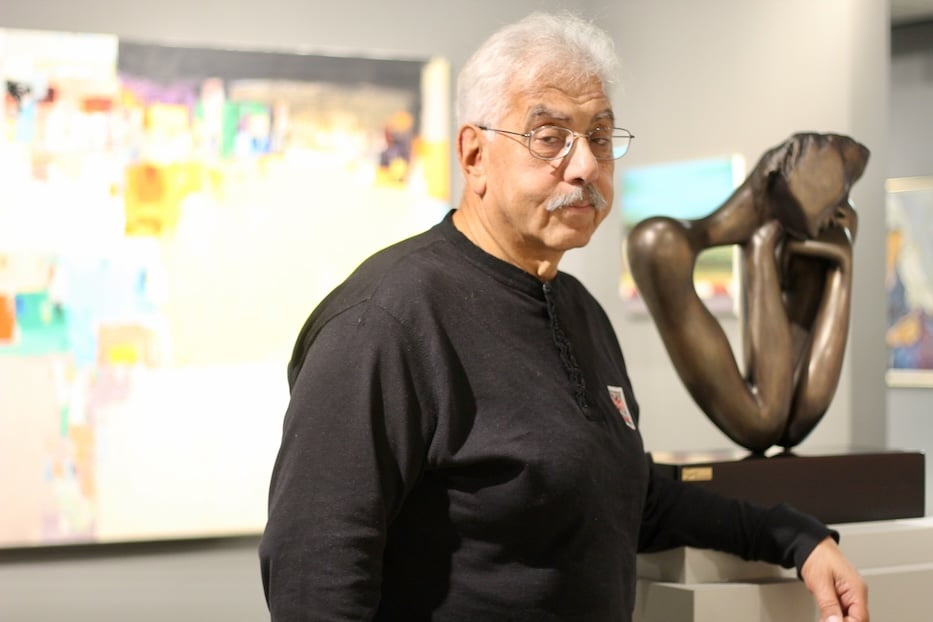

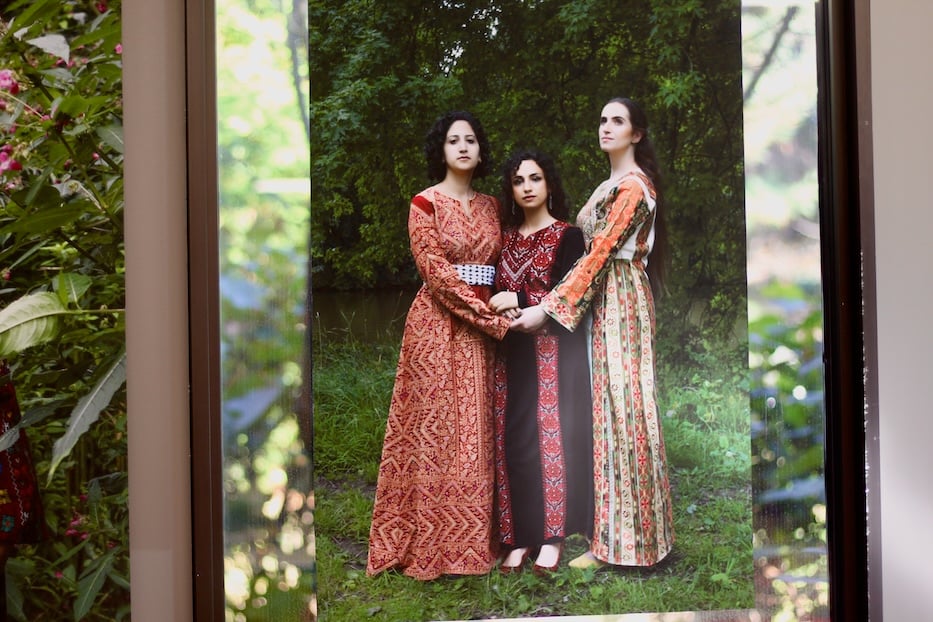

Top: Saleh with Sana Farah Bishara’s Contemplation. Bottom: A still from Tabea Marie Kerschbaumer's series 48 Stitches.

In one particularly striking image, three women stand together in a clearing, the foliage lush and dense behind them. All wear brightly colored thobes, the embroidery vibrant as they look towards the camera. In the center, one locks eyes with the viewer, her hands perched atop those of her peers. If a viewer looks closely, the hands appear to almost be braided into each other, as if they too are part of the cross-stitched pattern that sets the thobe apart from other garments.

In another, Kerschbaumer’s subject floats in an unnamed body of water, her thobe clinging to her body and darkening as it soaks all the way through. Through a sheet of water, bits of the embroidery peek out in blue and red and yellow, the ripples gathered at her knees, chest, chin. In the text she has written, she describes coming to Hanover, Germany for her graduate studies as a Palestinian who has always known a history of displacement.

“The Palestinian culture is for me my life,” she writes. In 1948, her grandmother left her home during the Nakba, or the forced migration of hundreds of thousands of Palestenians. In the decades since, her family has known refugee camps, diaspora, and migration, she explains—and through tradition, also worked to keep their culture alive. “The thobe is a symbol of Palestinian culture and in my eyes symbolizes the defense and resistance of the people.”

The portraits flow naturally into the next gallery, where several of Ghannam’s paintings ask a viewer to come in close and study her subjects as they mother their children, freeze midway through their conversations, and sell produce at the market.

In one, a bedouin woman looks downward, her face bursting into a smile as she lifts her hands to a covering that billows out at the sides of her head, the wind blowing on her gently. Beneath her beaded necklaces, a loose thobe explodes into color, with red and yellow flower shapes stitched carefully across the chest. The fabric folds and ripples at the shoulders, as though she is in motion.

In another, inspired by a visit to Jerusalem that Ghannam made years ago with her husband, a woman sells radishes, eggplant and herbs in the market, a thick bouquet of mint gathered in her hands. On her dress, layers of orange-red embroidery stand out against blue fabric and white sleeves, making her glow a terra cotta color against the warm stone wall where she is seated. Across the gallery, a woman leans against the stone around her doorway, sporting the same red-and-white thobe on display in the other room.

Installed among permanent collection items, they strike a chord with both garments installed throughout the museum, as well as multimedia work that addresses Palestinian identity and diaspora through past, present, and future. In Samar Hussaini’s 2017 Hope, for instance, the artist has started with the tradition of taṭrīz and used mixed media to build up a three dimensional, sculptural design, bits of fabric and paper collaged with text and newsprint.

For Saleh, who grew up in the West Bank and came to the U.S. with his family when he was 17, the objects help tell a story of tradition and resilience that is core to the museum’s mission. When he opened the museum five years ago, his goal was to both to celebrate Palestinian art and artists, and “to convince Americans that we are human,” he said. Along the way, he has folded in on-site and satellite exhibitions, film screenings, artist talks and performances meant to show the breadth of Palestinian culture.

Since October, he’s held onto the power of that work and of the exhibition as he grieves the violence and loss of life in Gaza. For him, taṭrīz is not just a cultural custom, but also a language onto itself, as intricate and layered as regional dialects and the words that get lost in translation. In the patterns, he sees a bridge to a home that doesn’t exist anymore—and an opening to talk about the richness and beauty of Palestinian culture in and across the diaspora.

“We’re fortunate that there are a lot of Palestinian artists everywhere, and a lot of them were really looking forward to having some of their work exhibited in the United States,” he said on a recent episode of WNHH Community Radio’s “Arts Respond.” “So we really were able to create an outlet for these artists to share their artwork with people here.”

That’s true across the museum, he added: since the space's opening in 2018, many of the objects in its collection have come from Palestinian artists and allies (Ghannam’s husband, Aziz Ghannam, is Palestinian) living across the diaspora. Installed against an old, greyscale aerial photograph of Jerusalem, for instance, there are two dolls in traditional dress, donated by a patron who heard about the museum and wanted them to have a safe home.

Elsewhere, there are sprawling landscapes, black and white photos showing Palestinian life between 1909 and 1948, and depictions of serene olive groves that feel particularly timely during a harvest that has withered under the weight of war.

It is all a logical entry into the newly-opened The Art of Gaza, an exhibition held in support of artists who are living in or connected to Gaza at a time when their lives and the lives of their families hang in the balance. Along one wall, painter Mohammed Alhaj has depicted migration and displacement in a way that feels existential, bathed in other worldly shades of yellow and purple.

On the canvas, long shadows stretch across the ground, the shapes and silhouettes nearly spectral. It’s here that Alhaj explores the concept of “Intiqal,” an Arabic word for migration that can also mean death. Nearby, Sana Farah Bishara’s Contemplation catches a viewer’s eye, as if the cast bronze head has found a moment of calm in the chaos. Across the gallery, a series from Bayan Abu Nahla shows the sheer exhaustion of living in conflict, as a figure presses her cheek to a red-knuckled hand.

Top: Detail from Mohammed Alhaj's Displacement series. Bottom: Sana Farah Bishara’s Contemplation.

When he walks into the gallery, Saleh said, it’s impossible for him not to think about the artists he knows who are currently in Gaza and the occupied West Bank, with whom he tries to check in every day. Like Palestenians across the U.S. and in the diaspora—and increasingly, a number of allies calling for a ceasefire—he worries constantly for their safety. Among those who have died include the artist Heba Zagout, who was killed alongside her two children in an airstrike in mid-October.

This month, it also comes as the museum petitions to have what is called a “Collateral Event” at the 60th Venice Biennale, which begins in April of next year. After exhibiting at the 2022 Venice Biennale, Saleh said that he sees the rejection of the museum’s proposal as a rejection of the 23 Palestinian artists whose voices would be otherwise included.

“This decision by one of the world's most prestigious cultural institutions not only silences these artists but also perpetuates a single narrative about Israel-Palestine relations,” he wrote in text that accompanies the petition. “The exclusion of Palestinian voices contributes to an incomplete picture that undermines efforts towards understanding and peace.”

The Palestine Museum U.S. is open from 2-4 p.m. each Saturday and Sunday or by appointment. For more information, including upcoming film screenings and events, click here. For more on the exhibition, listen to a video and exhibition tour here.