Books | Arts & Culture | Whalley/Edgewood/Beaver Hills

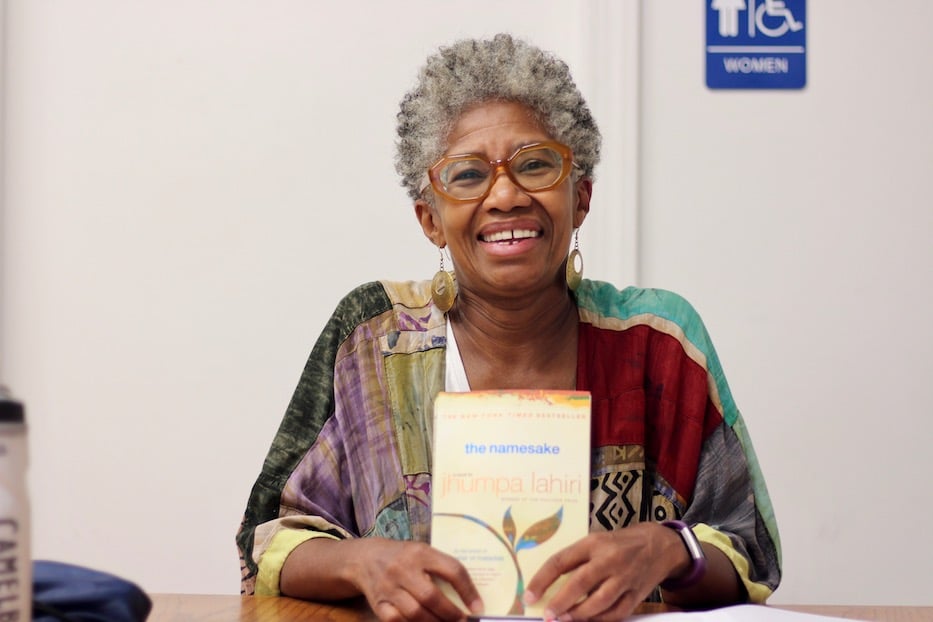

| IfeMichelle Gardin, who is spearheading the Elm City Lit Arts Fest. Lucy Gellman Photos |

The year is 1968 and Ashima and Ashoke Ganguli are in a Boston hospital room, struggling with what to name their baby when they are so far away from home. Or maybe it is 1994, and that baby has changed his name himself, because he doesn’t know exactly where it came from. Or it is 2019, and New Haveners Lyneece Gattison and Damonne Jones are swapping memories of a family nickname to keep it alive.

Those worlds collided at a new Whalley/Edgewood/Beaver Hills (WEB) sponsored book club, the first in a series of events leading up to the Elm City Lit Arts Fest next April. Both the club and the Lit Arts Fest are arranged by Beaver Hills resident IfeMichelle Gardin, who is spearheading the projects to promote and support authors of color and foster cross-cultural connections in New Haven. The books were donated to the book club through the International Festival of Arts & Ideas, which is supporting The Namesake through NEA Big Read and accompanying grant from the National Endowment for the Arts that came in earlier this year.

Gardin said that there will be a number of forthcoming salons and readings before the fest, scheduled for April 2020 (details and location are still forthcoming). On Sept. 10, the book club convenes again to discuss Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah at the Whalley Avenue police substation. The meeting begins at 6 p.m.

“As people of color, we all come from different backgrounds but have these familiar traditions,” she said Tuesday night, as members dug into Jhumpa Lahiri’s 2004 The Namesake. “We need to tell these stories, to reach back to move forward.”

| Damonne Jones, who brought her niece Lyneece Gattison. Pictured to her right is Lauren Anderson. |

The Namesake, which was also New Haven’s NEA “Big Read” book this year, follows Indian immigrants Ashima and Ashoke Ganguli as they settle into life in Boston. Ashoke is on a postdoc at Harvard, leaving Ashima alone and pregnant in a city where she knows no one. As she adapts to life around her, Lahiri deftly weaves in the story of their son Gogol, who shirks his name because he does not know the weight and beauty of its origins.

The novel begins in a small Cambridge apartment, but the story seemed close to New Haven as Gardin opened the book to chapter one and began spinning a web between Gogol’s fictional world and her own. At the beginning of the book, Ashima has to start code-switching the minute she gets on a plane to the U.S., carrying a few Bengali magazines and the histories of her culture that she must keep alive in a new country.

She’s pushed to compromise her customs almost immediately—first with poor American substitutes for Indian ingredients, then as hospital personnel tell the couple they must name their newborn son before leaving with the baby. For Gardin, it read as the tip of a huge cultural iceberg that didn't feel so distant at all.

“I think there’s an assumption that people are not content within their culture,” she said. She noted the widespread stereotype that hijabi women are somehow less liberated than their uncovered counterparts. She recalled visiting a mosque while she was in college, and meeting women who found immense autonomy in the choice to pray separately, cover their hair and dress modestly.

“They were so kind to me,” she recalled. “And they were like, ‘we good.’”

Nadine Horton, who chairs the WEB Community Management Team, chimed in. “We project our feelings onto them.”

| Nadine Horton: “There’s a lot of Black children who don’t know what their aunts, their uncles, their families went through." |

Gardin conjured New Haven during the 1960s, when her great grandmother lived on what is now Francis Hunter Drive in the city’s Dixwell neighborhood. Decades ago, she said, that street felt tight-knit in a way that it doesn’t anymore. Kids would drop by the house, and ask her great grandmother what she needed at the store. Neighbors looked out for each other’s children. Her great grandmother had a huge garden, a version of urban agriculture long before it was cool.

“Other people may have looked at it as ‘the hood,’ but it was a neighborhood,” Gardin said. “And this woman, Ashima, is trying to find that sense of community.”

Horton said it hit close to home for her too. In the book, Ashima frets about her English, self-conscious when she feels like her words have slipped in some way. She clings to her traditions but doesn’t always explain them to her children. She learns to adapt, but not without intense emotional labor and cultural loss. Every day, Horton finds herself switching her speech patterns—and the content of her conversations—for the people that surround her.

“It’s that code switch that happens all the time,” she said.

The book club dove back into the text. In The Namesake’s version of the 1970s and 80s, Ashima and Ashoke are raising Gogol between worlds. There are model U.N. classes and Levi jeans in Cambridge, summers in Calcutta that he resents the older he gets. There are small pizza parties for Gogol’s American friends, and big Begali gatherings for his parents.

But through it all, his parents take years to tell him the story of his namesake—Nikolai Gogol, the author who indirectly saved his father’s life—worried that it will cut him too deeply.

“There’s a lot of Black children who don’t know what their aunts, their uncles, their families went through,” Horton said. “There’s the sense that parents want to protect. But if you don’t know your history,“ you risk losing it.

Other members added that they see the same kind of erasure in Black and Brown communities, where shared history can also translate to intergenerational trauma.

As she read it, Gardin said, she’d thought about learning to quilt “the old way” at family gatherings when she was younger. Before she was born, her grandparents and great-aunts and uncles had moved to New Haven from North Carolina, bringing traditions of quilting and sewing with them when they moved to work at the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. As a kid, she thought of the traditions—pin basting each piece—as laborious and exhausting. Now, she said, she wishes she had paid more attention to the process.

“This is what this book reminded me of,” she said, adding her memories of Bowen-Peters School of Dance, a tiny and magical place that always smelled like sweat. “Those lost traditions. Because we all have that. Everyone has a story.”

Jones recalled that when she was growing up, her father told her that he was related to Frederick Douglass. For years, she assumed he was exaggerating. Then she tried an ancestry service, and found out that her family had been involved in the Black press, including running articles in Douglass’ publication The North Star. When she first received the results, she sat in the front seat of her car and cried.

“I felt for her,” Jones said of Ashima. “Here you are, in a new country, in the middle of winter, and she’s alone. She has no one. She had to feel devastated.”

As the hour wound down, members turned to the stories behind their own names, and the names of their children. Horton recalled that long before her daughter Taja entered the world, she heard the name, and wrote it into the fabric of a music box. The music box has long since disappeared—but Horton kept that strip of fabric. Gardin spoke to her daughter’s middle name—Amandla—a nod to Nelson Mandela two weeks after he was freed from prison. To laughs from the group, Lauren Anderson explained that the Boston accents with which she grew up meant that she pronounced her name more like "Lawn" until she got to college. Even now, she has an ambivalent relationship with her name.

“It’s interesting,” said Anderson, who made it just in time for the tail end of the group. "What our parents think of as weighting us may actually anchor us.”

The next meeting of the WEB Book Club is scheduled for Sept. 10 at 6 p.m.. The club’s next selection is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah. Meetings are held at the Whalley Avenue police substation next to Minore’s Market. The Elm City Lit Fest is scheduled for April 2020 at a New Haven public school; more details coming soon.