Books | Culture & Community | Education & Youth | MLK Day | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | Yale University | Literacy

Top: Nick Wantsala, the Kenya S. Flash Resident at the Yale Library. Bottom: Wantsala and Tamara Michel, program coordinator at the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, read to students from Lincoln-Bassett Community School. Lucy Gellman Photos.

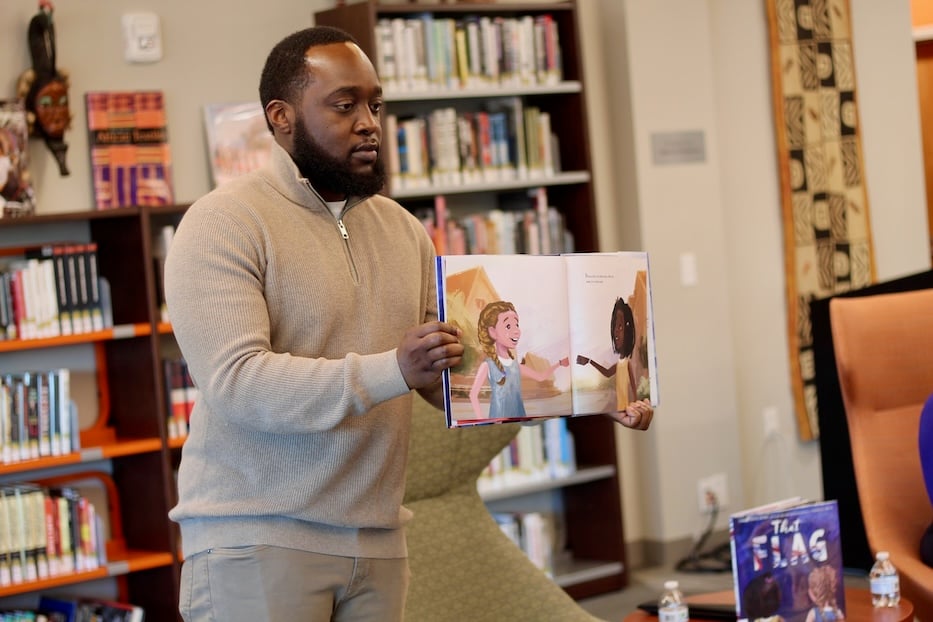

On the second floor of the Stetson Branch Library, 10-year-old Ayssatou sat suspended between two universes, her eyes darting from reader Tamara Michel to her teachers behind her, and then quickly back to Michel. At the front of the room, librarian Nick Wantsala held open a copy of Tameka Fryer Brown’s That Flag, so students could follow along with every word as Michel read. On the page, two friends stood face-to-face, suddenly at odds with one another.

Bianca, on the left with a blue dress and straw-colored braids, insisted that that flag—the Confederate flag—stood for Southern history and heritage. On the right, her friend Keira, her brows furrowed with one arm raised, saw it as a symbol of contempt and fear-mongering. Ayssatou, who is rarely at a loss for words, didn’t know exactly what to think or say.

Ayssatou is a fourth grader at Lincoln-Bassett Community School, where students are diving into the history of the civil rights movement around MLK Day celebrations across the city and the state. Wantsala and Michel are staff members at Yale University, where they are both on the coordinating committee for the university’s 2026 Citywide Read.

On a recent Tuesday morning, their universes came together at the Stetson Branch of the New Haven Free Public Library, as students gathered for a history-drenched storytime and talkback. In the initiative’s second year, the committee selected Brown’s That Flag, which the author was inspired to write in the wake of the violent, white supremacist killing of nine Black parishioners at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in 2015.

“At first, I was kind of hesitant, like, ‘Is this story too much for this time frame?’” said Wantsala, the inaugural Kenya S. Flash Resident Fellow at the Yale University Library, who worked closely with Stetson Young Minds & Families Learning Librarian Phillip Modeen to make the event a reality and get the book into schools across the city. “But really, this story is what’s needed right now.”

As students headed up to the library’s second floor, that approach sprang to life in vibrant color, classmates settling into an open space has become home to countless readings, literary festivals, puppet shows, celebrity drop-ins and even a few rafter-raising concerts. At the front, Michel and Wantsala greeted them excitedly, bright copies of the book already in their hands.

“Are you all familiar with the American flag?” Wantsala asked. A few hands went up.

“It’s all the countries … the states,” Ayssatou self-corrected of the white stars printed neatly across one corner, snuggled in a rectangle of navy blue. She propped herself up on her knees so that she could see her classmates even from the back of the group, where she sat near teachers Julie Votto and Oluchi Okeke.

“Does anybody know how many stripes there are?” he continued.

“Thirteen!” offered 9-year-old Savannah with a smile, the bright barrettes in her hair moving as she spoke. A second small hand rose from across the room, where 8-year-old Jean leaned against a column. This year, he’s at Lincoln-Bassett as an exchange student from France, while his mom does postdoctoral research in New Haven.

“For the original 13 colonies in America,” he offered through a thick accent. Then gently, he moved toward the topic at hand, gesturing to the cover of the book.

“We will be talking about a different flag,” he said. When he referenced the Confederate flag, the room remained mostly quiet, a few students staring back blankly, or with eyes full of questions that hadn’t yet been answered. As Michel opened the book and began to read from her seat, Wantsala flipped to the first pages, holding the illustrations out toward the group as students leaned in.

“Bianca and I are almost twins,” Michel began, and ears in the room held on to every word. On the first page, two young friends went in for a fist bump, beaming. Keira, the narrator, was Black. Bianca, her friend, was white. “We’re the same in so many ways. We both wear our hair in braids. We spent independent reading time together. We play four square better than anyone in our class.”

In the library, students let the words transport them. Somewhere in the American South, Bianca and Keira tumbled through adolescence side by side, their smiles radiant as they navigated school together. In one image, the two pored over an open book, Keira pointing out something on the page with one hand, as the other embraced her friend. In the next, they jumped toward a volleyball, Keira’s limbs flung outwards as if she was flying.

Tamara Michel, program coordinator at the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, with fourth grader Marcus after the reading. "I didn't know that that flag was full of hate," he said.

Except, it was a friendship limited to school hours, on account of the huge Confederate flag flying in front of Bianca’s family’s home. Or in Keira’s words, “that flag.”

“Mom and dad say it’s a hate flag, a symbol of violence and oppression,” Michel read, her voice steady and calm as a few students raised their eyebrows, or turned furtively back toward Votto and Okeke to gauge their reactions. “Bianca’s parents told her it’s a heritage flag, a celebration of courage and pride.”

Back on the page—the book’s illustrations come from artist Nikkolas Smith, who also did the artwork for the children’s adaptation of The 1619 Project: Born on the Water—students could see the flag in question in real time. Beside a house with pruned hedges and a large porch, the Confederate Battle Flag—an image that has become synonymous with segregation, horrific anti-Black violence and white nationalism—flapped in the breeze. Some of the students later said that they’d never seen the flag before, or not yet learned the history of the Civil War.

Back inside Stetson, a person could have heard a pin drop. In Brown’s world, which did not feel all that far away from New Haven, Keira and her class prepared for a field trip to a “Southern Legacy Museum” (inspired perhaps by the E qual Justice Initiative’s real-life Legacy Museum), where an exhibition on the antebellum South opened to a display of objects from the civil rights movement. At the center of it all, Keira could see the Confederate flag, there as a symbol of subjugation and white violence.

In the room, a few students breathed sharply, or glanced at each other as they took in the scene. When the two friends reunited on the page, a tension sat uncomfortably between them, the shape of a conversation waiting to happen. In both the book and at Stetson, students looked for the trusted messengers among them—teachers, parents, librarians—to help carry that story.

The setting at Stetson is fitting: while Keira’s family broaches “the talk” with her at home, Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown has worked for over two decades to build a space to speak candidly about race and racism in this country, including in a time when those discussions are both increasingly scrutinized on the federal level, and increasingly vital to have in and with community. As Keira learned about the civil rights movement, legislation that followed, and the ongoing, unrelenting violence of white supremacy, so did students, some of them for the first time.

“We talk about the things Black people have to do every day to stay safe,” Michel read from the book. “I feel scared, confused and mad, but mostly sad.”

Savannah and Ayssatou. Teachers asked that the Arts Paper use only their first names.

In the book, Brown pushes deftly back against any sort of tidy resolution, in a way that feels completely true to the present. Instead, Keira—still reeling from all that she has absorbed in the past day—must contend with the ease with which white people can move through the world, without even recognizing that it’s there. It’s a reality that many students in New Haven are living with every day.

When both of them have to face an act of unspeakable, racially motivated violence to which the Confederate flag becomes the backdrop, they talk it out. They have to. And Bianca’s family starts to learn about the process of unlearning. As dominant narratives begin to dissolve on the page, there’s a sense that they can for the reader, too.

“A lot of what this story is about is just listening to each other,” Wantsala said afterwards, as students returned mentally to the room and began chiming in with their thoughts. Ayssatou, propped up on her knees, was still working through the disagreement that the friends had had over the flag. Nearby, her friend Savannah said she'd been taken aback by some of the violence in the book. “I never knew some white people can be bad,” she said.

"I didn't know that that flag was full of hate," said her classmate, Marcus, moments later.

“Do you think Bianca and Keira are gonna be friends again?” Michel asked.

“Yeah!” Ayssatou said enthusiastically. Taking a beat, she added that “I knew about slavery but I didn’t know that they had a Confederate flag.”

“I learned a lot of stuff,” she added in a conversation afterwards. Growing up in New Haven, she’s absorbed bits and pieces of history from both her teachers and her parents, including recently in two books on Martin Luther King, Jr. and Harriett Tubman, she said. But something about Brown’s words resonated with her on a deeper level, because they sounded like something she’s heard at home. “My dad and my family be saying, ‘I wish we were all together.’”

“I want to be a teacher so I can educate kids,” she added—just as librarians had done for her that morning.

Downstairs, she took a step in that journey as she designed a flag, chatting with classmates about the sweeping, bright design as she worked. On the page in front of her, the black-and-white outline on the page had become a cacophony of color, with bands of yellow, pink, blue and purple by the time the school’s buses turned on their engines around the corner.

Before leaving, she explained that she was still debating a name for the flag, but leaning towards “Blossom” or “Vanessa.”

“It’s like a flower,” she said. “And we’re all together, kids and communities and friends and families.”

That’s part of the hope behind programs like the Citywide Read (not to be confused with the NEA Big Read, which the International Festival of Arts & Ideas plans to kick off later this spring). Michel, a member of Yale’s Citywide Read committee who grew up in Trumbull and now works as the program coordinator at the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, noted how the story opened up new avenues for discussion, especially among young readers.

“The first time I read it, I was taken aback by how real the words were, how they jumped off the page,” she said. “Although there are these differences from the past, they [the characters] had the opportunity to come together and make their own present.”