Books | Culture & Community | Dixwell | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | Yale University | Elm City LIT Fest | Dixwell Community Q House | Kulturally Lit | Romance

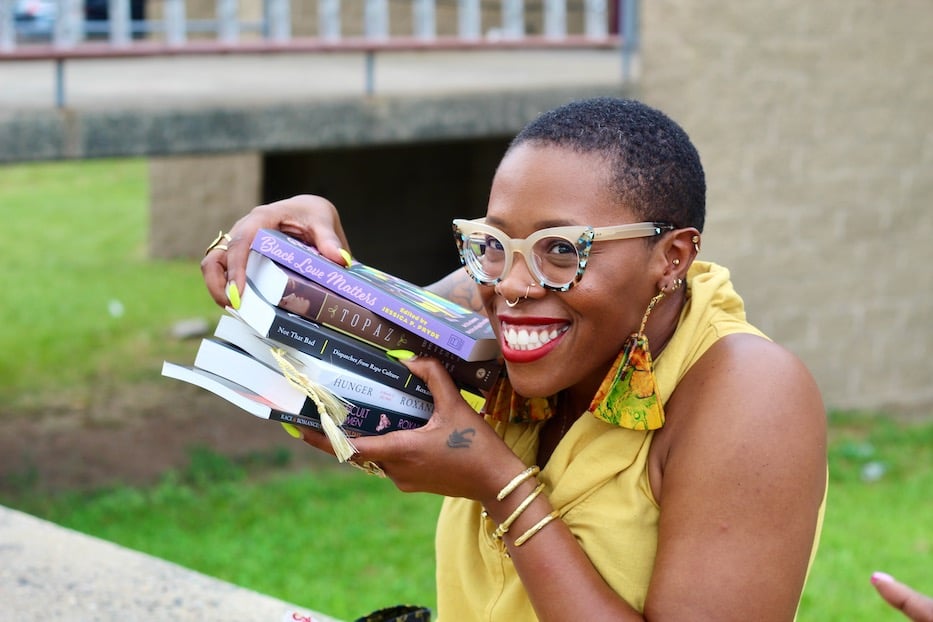

Krystal Marquis and Margo Hendricks ("I'm a badge thief!" she joked of wearing author Nicole Jackson's badge during the presentation). Lucy Gellman Photos.

For author Margo Hendricks, Romance was a way to explore the very real history of class, race and power in Elizabethan England. For Tara L. Roi, it was a place where she could talk about climate change, and convince readers to listen. Krystal Marquis and Adriana Herrera just wanted to read about people who looked like them—and realized they would have to literally write the book.

In the process, they liberated the genre from its box—and made space for writers, readers and stories whose voices have always existed, but often been gaslit, whitewashed, and asked to edit themselves out of the narrative.

Authors, artists, and over 100 bibliophiles brought that expansiveness to Stetson Branch Library and the Dixwell Community Q House Saturday, as the fourth annual Elm City LIT Fest celebrated the "Literature of Hope" with author panels, workshops, art activities, performances and a book fair in the building's multipurpose gym. The event was organized by Kulturally LIT, a small but mighty team which buzzed around the building all day.

For the first time this year, the festival partnered with the Department of African American Studies and Popular Romance Fiction Conference at Yale University, held Sept. 8 and 9 between Yale's downtown campus and the Q House. Over two days, the conference included author talks, workshops at Stetson and at Yale, and a Saturday evening keynote from romance writer Beverly Jenkins and cultural critic and author Roxane Gay.

Top: Elm City LIT Fest Founder IfeMichelle Gardin. Bottom: Diamond Tree of Hood Hula.

"I'm full of gratitude," said LIT Fest Founder IfeMichelle Gardin, who has grown the festival from a grassroots book club in a tiny police substation to an hours-long annual event and literary organization that operates all year round, and will next year celebrate James Baldwin's 100th birthday. "I'm so grateful that this bookfest has evolved and I'm so excited for what's to come."

While “the literature of hope” may be a title that comes from the romance genre itself, that sense of possibility took on many forms Saturday, from music and multimedia art to the announcement of New Haven’s inaugural poet laureate (stay tuned for a full article on that). By late morning, it crackled through the humid air, attendees beating the heat as they made a loop around the Q House's patio and trickled into the open gym.

Outside, vendors set up tents with books, jewelry, and clothes in bright African prints, some dancing along to the bell-like, ringing of steel pan as Caribbean Vibe Steel Drum Band and St. Luke's Steel Band took over the space. Across the patio, hula hoops materialized, and attendees moved along with the sound as they made their way through the thick heat. The festivities were not even a full hour in, and already it felt like a celebration.

On the first floor of Stetson, the party was just getting started. Across several low tables covered in markers and sheets of white paper, pint-sized attendees gathered for storytime from author Abdul-Razak Zachariah and crafting with artists Candyce “Marsh” John and Isaac Blodoworth, turning a corner of the library into a temporary studio space.

Artists Candyce "Marsh" John and Isaac Bloodworth.

As they fashioned paper-and-stick puppets and collages with construction paper crowns, young artists channeled that hope across their canvases, with designs that burst into color. Sarah Beckford, who came with her 3-year-old daughter Marley, praised the festival as giving Marley a space to play with other kids—and fall in love with literature.

“It feels awesome to be included in the community,” said Marsh, who added that she loves a good Black love story, and was excited to be joining LIT Fest for the second year in a row. When she heard that the theme of the conference was romance, she started thinking about the importance of free self-expression and self-love. Among canvases and paper cutouts, she brought back her signature crown cutouts to remind kids that “we all are royalty.”

“The better we can love ourselves, the better we can love each other,” she said.

That interest in self-expression echoed all the way down the hall in the gymnasium, as dozens of authors set up for a book signing. At one table, author Katrina Jackson laid out copies of her novels Every New Year and Back In The Day, almost all of which were gone by the end of the afternoon. A historian at Bowling Green State University, Jackson said she writes romances on the side, and looks forward to events like LIT Fest where she can bond with other authors.

Top: Sarah Beckford and Marley. Bottom: Author Katrina Jackson.

“It’s beautiful, honestly,” she said of LIT Fest, and particularly its emphasis on Black voices across the diaspora. “Sometimes you’re in these romance spaces where there are one or two [Black authors], or just a few.” A conference centering and celebrating those voices gave her space to have new and lively conversations with fellow writers that she would be taking back with her to Ohio.

One of them was with author and romance novel collector Briana Smith, who said she gravitates towards the genre for the very expansiveness that fellow writers applauded throughout the day. She doesn’t read the novels to run away from the world’s problems--she reads them to remind herself that love, in many forms, persists throughout them.

“I love that anything is possible and there’s a happy ending,” she said, adding that she was excited for the sheer amount of representation on display. “I think it shows the growth and progression of society—it’s taking the shame away, and seeing something that you’re experiencing in the real world.”

Nearby, author, academic and Black Romance Podcast founder Julie Moody-Freeman said that she was excited to be part of the conference, and specifically of LIT Fest. “What I like about this is that it combines the writers, readers and the scholars,” she said. “It brings together everybody.”

Nowhere was it clearer, perhaps, than in "Black Romance Spotlight: Discussion on the Power, Politics and Provocations of Black Popular Romance," held on Stetson's sprawling second floor. As two dozen book nerds, literary luminaries and ravenous romance readers took their seats, panelists Margo Hendricks, Krystal Marquis, Tara L. Roi and Carole V. Bell each made an argument for the sheer breadth of romance literature, pointing to the window it can open to history, fantasy, power, and untold and undertold narratives.

Ryan Lindsay, the author of Mine The Unseen, moderated the discussion. From jokes that broke the ice (“Do not give it to your children,” Herrera laughed of her work; “It’s so phallic!” Hendricks said in a deadpan as she received the mic) to their own personal triumphs, all six centered the importance, thrill, and sheer depth of romance writing, which often gets an intellectual short shrift despite its popularity and ability to gross billions of dollars in an otherwise struggling publishing industry.

That’s particularly true of Black romance, a genre that is continuing to grow as more readers and writers look for books with their own lived experiences. Or as Herrera, who is the co-founder of the Queer Romance POC Authors Collective, said, "I get to envision futures and lives and love stories that are for us, right?"

Tara L. Roi and Adriana Herrera.

"That's what romance is for me in terms of a writer,” she added, pointing to the first book in her Las Léonas series, A Caribbean Heiress In Paris. Before writing the novel, she learned that there was a significant Dominican presence at the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris, France. The history surprised and delighted her. She also knew that if she wanted other people to know that history, she would have to write it herself. That’s been a constant in her books, from The American Dreamer series to On The Hustle.

“How many times do we get to read about Dominican women going to Paris in the 1800s to sell rum and have a great time?" she asked to laughs that subsided when she side-eyed the readers who insisted that it must be fantasy. “I write romance with the intention of being able to write about the history of the place that I come from.”

The point resonated with Hendricks, who is also a Shakespeare scholar and professor emeritus at the University of California at Santa Cruz (she publishes romance under the pen name Elysabeth Grace). Like Herrera—and many romance writers—she uses the genre as a platform for the history of race, class, culture, medicine and economics. That started, she said, when she began reading history and realized that she wanted to know more about people who looked and lived like her.

Bell, Tara L. Roi, and Herrera.

In her 2022 novel Elizabethan Mischief, for instance, she was able to take a real medical phenomenon—twins born to the same mother, with different skin pigmentation—and fold it into a story of romance, revenge, racial passing and social and economic mobility in sixteenth-century England. It was hundreds of years and an ocean removed from Nella Larsen and Britt Bennett—and it was a history most readers had no idea existed.

"Race has tentacles. Gender, sexuality, religion, and class,” she said. “Flip it over, class has tentacles—sexuality, etcetera. You can do that with the whole thing. You cannot just do it with one."

Marquis, whose bestselling novel The Davenports came out of a NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) challenge, also looked at how “romance” can take people far beyond the scope of romantic love. In The Davenports, she originally wrote her protagonists as enemies and rivals. Then she reflected on her own female friendships, including five women with whom she is especially close, and rewrote them entirely. In the book, to which there is a sequel coming out next May, they are best friends.

"I think it really opened up the conversation of girls getting along, girls supporting each other, girls rooting for each other and that was really important to me," she said. "My group of friends, there's six of us, and whenever somebody has something important, we always get together, we're always rooting for each other, speaking each other's names and accomplishments in rooms that they're not in. I wanted young readers ... to see those healthy girl-to-girl relationships and share in each other's wins."

Top: Author Krystal Marquis and New Haven educator Dee Marshall, who works at Hill Central School. Marshall said she'd love to see The Davenports become part of New Haven's literacy curriculum. Bottom: Markeshia Ricks, who moderated a panel on The Davenports, with her haul.

While she’s thrilled that adults are reading The Davenports, she added, she hopes that young women and girls will also pick up the book, and hold tight to the reminder to build each other up instead of tearing each other down. It is currently marked as eighth grade and up.

"The relationships that they have when they do fall in love teaches them a lot about themselves, their personalities, their goals, what they want to do in life,” she said. “I think a lot of romance is not only discovering who is a good fit for you, but discovering yourself."

Some also noted the importance of those who had blazed the trail, including Jenkins. Bell, who transitioned from academia into cultural criticism, remembered getting a pitch from the New York Times around 2021, asking her to review Jenkins’ novel Wild Rain. It was a moment in which she realized the debt she owed to those that had stuck with the genre for generations, and kicked open a door of sorts.

"I feel like I'm standing on the shoulders of people who did that hard work of breaking through and demanding respect for romance," she said. Lindsay pointed to her focus on "Black solidarity, liberation, and power"—as well as joy—in a 2022 article she wrote for Nonprofit Quarterly. In the piece, which later appeared in the anthology Black Love Matters, Bell tied Black romance novels to Black wealth building and financial security.

"I'm a believer in sticking close to the text, and really trying to understand what the text is telling me," pointing to characters in Christina Jones' I Think I Might Love You, Alexandria House's Let Me Free You, and Alyssa Cole's How To Catch A Queen.

All, at some point in the discussion, added that romance (and romance on their terms) can be and has been a path to healing. Roi, whose real-life alter ego is the Westville-based writer Rebekah L. Fraser, recalled how cathartic writing has been for her in the midst of an extremely difficult year. While her subject matter may be heavy—she is currently finishing the third book in her Love and Disaster trilogy, which yokes romance and climate change—the process of writing itself is joyful.

“Writing romance is where I go to heal, and where I go to make sense of the world,” she said. She recalled writing a scene for her forthcoming novel, a process that she starts with dictation while she’s on her rowing machine, and then edits down until she’s satisfied with it. As she talked through the scene, which takes place against the backdrop of the California wildfires, she began crying in character. Then she started “sobbing ... as me."

Her books have also given her a space to claim and explore her biracial identity “unapologetically,” she said. In those pages, she’d been able to bring to life voices and experiences that are both based on her own, and explore the creation of race and class to maintain systems of unearned power in the U.S. and across the globe.

”I am actually the embodiment of what's possible for this world when we stop paying attention to things that don't matter and stop being controlled by fictions that are designed to separate and oppress," she said.

Herrera, who grew up in the Dominican Republic, moved to the U.S. at 23, moved temporarily to Ethiopia for five years and then moved back, said she too finds delight and pleasure in romance writing. In part, it’s because she’s giving a voice to her lived experience, which she didn’t see reflected anywhere in the genre. In every place she’s lived she’s had to negotiate her Blackness. Why not have characters that could do the same?

"I have to think about, how can I be part of the conversation of like, love and liberation and sex positivity and undoing harmful beliefs within my Black Dominican community and also within this larger diaspora that I'm a part of knowing," she said.

"Part of what white supremacy does is make us feel that our experience is happening in isolation,” she later added. “Like, we are the only people that have experienced this atrocity. They want to keep us in a vacuum where we can't go to each other to heal, right? To me, part of what I hope I do with my books is just present the vastness and the depth of what the Black identity is in this world."

Hendricks added that she’s proud to have stayed with romance writing entirely on her terms, a resilience she may have built up in part because of her time in academia. For years, publishers told her that they couldn’t relate to her characters, and asked her to make them white. Each time, she refused. Then in 2015, she heard Jenkins speak on a panel, and encourage writers to follow the narrative they had imagined.

“I knew that's what Ms. Morrison said,” she said. “But hearing it from a romance writer was so important to me. That's what I'm proudest of. I'm writing the books that I want to write."

Learn more about Elm City LIT Fest and Kulturally LIT here. Learn more about the Popular Romance Fiction Conference here. Stay tuned for an Arts Paper article about the first-ever Elm City Poet Laureate, announced Saturday afternoon, this week.