Books | Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | Whalley/Edgewood/Beaver Hills | Arts & Anti-racism | Possible Futures

Third graders from L. W. Beecher Museum Magnet School of Arts and Sciences. Lucy Gellman Photos.

On a wintry Edgewood Avenue, Abdul-Razak Zachariah cracked open the spine of The Night Is Yours, and transported young readers to another universe. In the pages, night was falling over a West Haven apartment complex. It was summer, and the heat wrapped everything in its sticky embrace. Guided by the moon, a young girl named Amani slipped outside to play hide and seek.

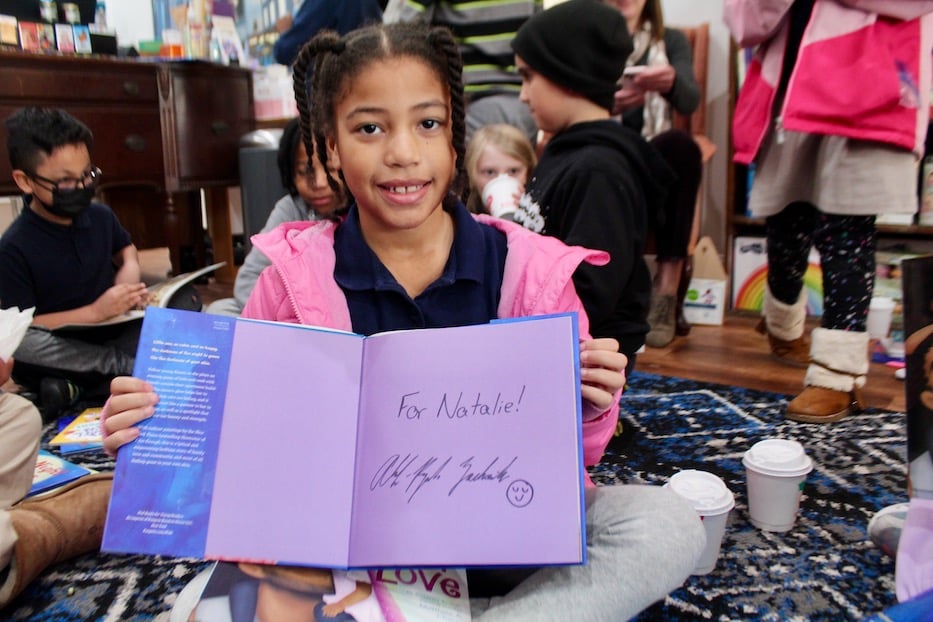

As she watched the pages turn, 8-year-old Natalie Napoleon saw an image of herself, looking up at the sky. She leaned forward, kept one eye on the butter-colored moon, and stepped into the story.

Zachariah is the author of The Night Is Yours, a children’s book inspired by his sister, high school senior Aisha Nabali, and illustrated by Keturah A. Bobo. Natalie is a third grader at L. W. Beecher Museum Magnet School of Arts and Sciences. On a recent Thursday, books brought them together at Possible Futures Bookspace at 318 Edgewood Ave., as part of a grade-wide initiative to spark literacy and spread representation during the holiday season. As part of it, every student in Beecher’s third grade class left with two new books, including a signed copy of The Night Is Yours.

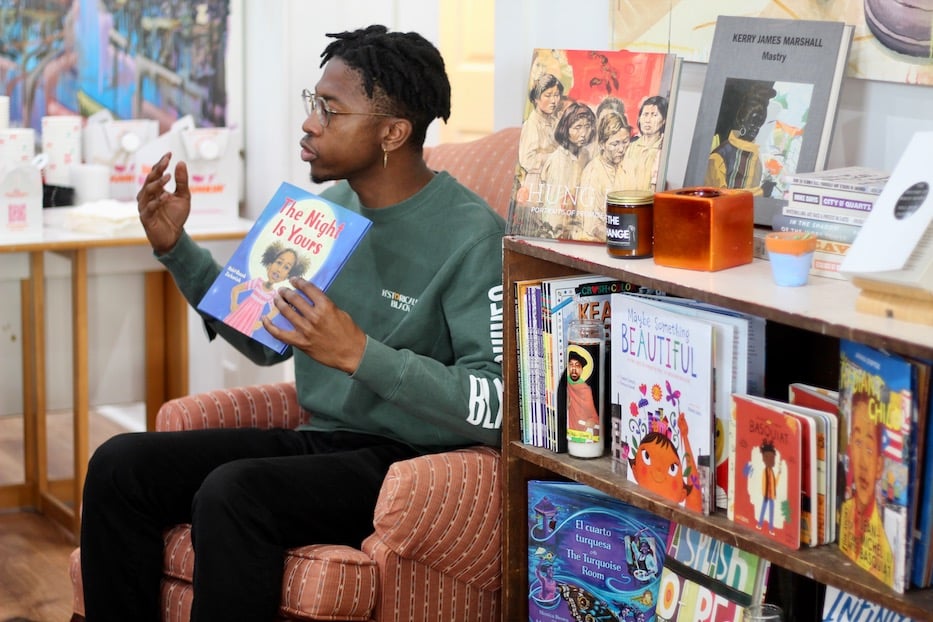

“I was really interested when I was in college in how people of color were represented in books,” Zachariah said as students took a seat on the rug in front of him and got cozy. “I’m always inspired to keep writing because people are excited to see themselves in stories.”

The Night Is Yours author Abdul-Razak Zachariah, who grew up in West Haven and now lives in Massachusetts.

The visit grew out of a love for books and book joy among Zachariah, bookspace owner Lauren Anderson, and Beecher Literacy Coach Lauren Canalori. In 2019, Zachariah published The Night Is Yours with Penguin Random House after studying the underrepresentation of Black characters—and Black authors—in children’s books as an undergraduate at Yale. As he wrote, he imagined Aisha slipping outside Terrace Heights, the West Haven apartment complex where they grew up, and playing by the long beams of moonlight that fell over the grass.

In the book, he named the character Amani, which translates to “wishes” in Arabic. Visits like Beecher’s are especially close to his heart, he said; the students remind him of kids he went to elementary school with. While he went on to pursue sociology at Yale and graduate work in education and urban planning at Harvard, he’s never forgotten the West Haven home where his own story began.

Mason Miranda and Fatoumata.

As students streamed into the bookspace, Zachariah welcomed them to a soft reading rug, taking a seat as he introduced himself to the class (his joke that he is now in the “18th grade,” shorthand for grad school, drew both awed murmurs and giggles). Nabali, the real-life star of the book, stepped back between two sturdy wooden bookshelves, listening with a copy of bell hooks’ All About Love slack in one hand. Sugar, the bookstore’s friendly dog, curled beneath the heavy desk and settled in for storytime.

“Little one, so calm and so happy, this is your night” Zachariah began. On the first pages, Amani appeared in a pink-and-white dress and purple socks, with a smile wide enough for the whole solar system. In her face, some students later said they saw their sisters, their cousins, themselves.

As he read, Zachariah was no longer on Edgewood Avenue, but back at Terrace Heights, watching his sister dart among the trees and stoops and leaf piles playing hide and seek in the sun-warmed grass. On the pages, Amani bounced from her apartment to the steps outside, catching the breeze after a day of unrelenting summer heat. Matching pink ribbons held back two curly brown puffs, dancing above the pink and white of her dress. She burst into a smile and chatted with her friends. It was time to play.

Aisha Nabali and Abdul-Razak Zachariah.

“You are very real tonight brilliant girl, as you laugh with other kids in the courtyard, and double dutch to the rhythm of hip-hop coming from a nearby apartment’s window,” Zachariah read, and then paused. “Does anyone live in an apartment?”

“Me!” yelled Mason Miranda from the middle of the group, bodies suddenly squirming as hands went up. “I lived in an apartment when I was three years old!”

“Yeah? Wow!” Zachariah smiled. Yellow light gleamed from the windows of an apartment building illustrated on his lap. “So I lived in one too when I was three years old. This looks like the apartment complex that me and my sister Aisha grew up in, and had a lot of kids playing in.”

Some students nodded wordlessly, as if to say Yes! And Cool! and Me Too! Back in the story, Amani was counting on the moon as her friends found their hiding spots. She pulled her eyes shut, and Beecher students studied every detail to see what would happen next. The sound of laughter filled the apartment’s courtyard, and a few giggles bubbled up through Possible Futures. Amani began to find her fellow hide-and-seekers, the moon glowing on her skin.

Arelys Caporal after the reading.

“So bright!” piped up a small voice from the back row. “It’s like a night sun,” ventured another. “A night light!” said a third. Zachariah beamed. In the book, Amani was well on her way to winning the game.

“Does anyone like looking outside at night?” he asked. “Does it make you feel calm? Peaceful?” Over a dozen hands went up. On the page, Amani ran toward her dad with a huge smile and outstretched arms. Back on the reading rug, friends Natalie Napoleon and Arelys Caporal looked closely as the illustration came into view. They burst into applause moments later, when Zachariah announced the end of the story.

As she nibbled on a donut and looked over a new copy of Matthew Cherry’s Hair Love after the reading, Natalie said The Night Is Yours stayed with her because she loves looking up at the moon from her own New Haven home, usually with her younger sister at her side. She loved the origin story of the book, and the real-life connection to Nabali.

“It’s super beautiful,” she said. “It reminds me of me.”

“His voice was really calming,” chimed in eight-year-old Fatoumata, who said that she saw in the narrative bits of her own upbringing as the child of immigrant parents from West Africa. When Zachariah told her that he grew up on stories of Anansi the Spider, she burst into a smile. “The place reminded me of places I’ve been.”

Natalie with her signed copy. “It’s super beautiful,” she said of the story. “It reminds me of me.”

As she headed toward Zachariah to get her copy signed, 9-year-old Luz Rose Arias said she was still coming off the excitement of meeting an author for the first time. While her favorite genres are horror and mystery—her current obsession is Roald Dahl’s Matilda—“it was really great” to hear Zachariah read, she said. She loved learning that his story wasn’t so different from her own, and that she too could be an author when she grew up.

As students browsed books and sipped hot cocoa after the reading, Canalori said that the visit is part of a wider effort to keep kids reading, particularly as New Haven faces a city-wide literacy crisis. This year, the literacy coach started thinking about what it would take to provide culturally responsive books to every third grader in the school, or roughly 40 students. Without funding from the district, she turned to “incredibly generous” friends and family with a goal of $600, or two books for every student.

“My whole goal this year is to just make book joy,” she said. “If I could bring the whole school, I would.”

She was thrilled to work with Possible Futures, she added; “I come here when I need a little pick me up.” Because of the space’s size, half of the third grade class met with Zachariah; the other half met with author Winsome Bingham, whose book Soul Food Sunday was published in September 2021.

Student Luz Rose Arias.

In the New Year, Anderson is continuing to grow a “book joy” fund to provide similar opportunities for kids who want or need new books, but may not be able to afford them. She stressed the importance of giving students access to books and to resources that inspire and encourage them to read.

“I think that visits like these are really wonderful for kids to experience joy related to and surrounded by books,” she said. “And also that we could see more of this happening in schools if all of our schools had fully funded school libraries and fully funded library media specialists.

"If anything, I think there’s an argument in all of it for not just full-time library media specialists and open libraries for the nine months of the school year, but for the entire 12 of the calendar year.”

Back on the bookspace’s corner couch, Zachariah said that he is working on two new book projects, one geared toward children and the other toward young adult or YA audiences, but has struggled to find time as he finishes his graduate degree in urban planning. Every so often, he smiled across the room at Nabali, who recently received an acceptance letter from Barnard College, her first choice school. She hopes to study neuroscience and film, she said.

“Sometimes we have people of color in the book, and people accept that as enough,” Zachariah said. “I’m trying to elevate that representation can look like quiet and mundane moments,” like a young Black girl playing hide-and-seek with the moon’s assistance.

“I like it!” Nabali added of the book. “It’s kind of surreal seeing someone who is supposed to be me in print. I don’t remember that many books that we had that showed Black children when I was young. It’s good for Black children to see themselves in a way that I didn’t.”

Want to contribute to the Book Joy fund? Readers can participate by sending a payment with the memo “Book Joy” or the hashtag #BabzBookJoy to Possible Futures (@possible-futures) on Venmo or leaving a donation at the bookstore. Possible Futures is closed through Jan. 13.