Culture & Community | Dixwell | Arts & Culture | News From The Pews | History | Arts & Anti-racism | Dixwell UCC

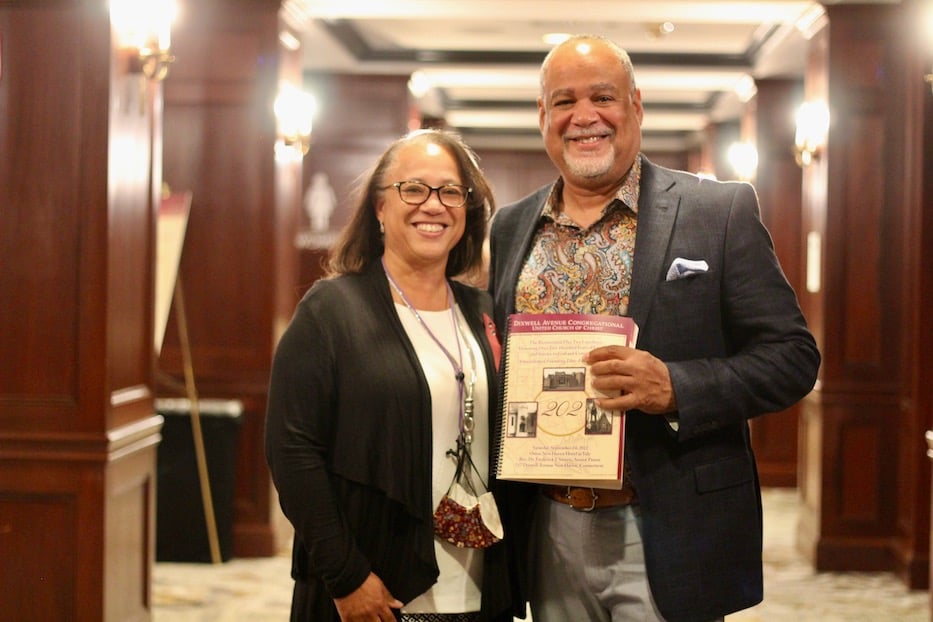

Tracey Twitty-Philpot and Michael Twitty. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Siblings Michael Twitty and Tracey Twitty-Philpot don’t remember their lives before Dixwell Avenue Congregational United Church of Christ. As babies, they were christened in the church. As children, they ran beneath its pews, delighting in the round, resonant sound that filled the space. When they grew up, both got married in the church, then chose to stay as they started families of their own.

So when it came time to celebrate the church’s legacy, it only made sense that they showed up together. If they were going to fête the oldest congregational Black church in the country, they wanted to do it side by side.

Saturday morning, Twitty and Twitty-Philpot were two of almost 300 parishioners, faith leaders, supporters, and extended church family members at Dixwell UCC’s “Bicentennial Plus Two,” a 202nd birthday party and luncheon held at the Omni in downtown New Haven. For over four hours, attendees filled the hotel’s second-floor ballroom with ringing laughter, warm conversation, and their memories of the church.

The event doubled as an awards ceremony, at which the Amistad Committee, Inc., George W. Crawford Black Bar Association, Greater New Haven NAACP, Greater New Haven African American Historical Society, and Dixwell Community Q House all received recognition for their service to New Haven. In between speakers and an awards ceremony, William Fluker and Lisa Bellamy Fluker kept the music flowing.

Top: Educator Sean Hardy with Kathi Williams, Ann Robinson, and Judge Angela Robinson. Bottom: Streets, who has served as senior pastor at Dixwell UCC since 2013.

"Could you, with me, just take a deep breath in of gratitude, for just today's presence of all of you?" said Rev. Frederick J. Streets, who has served as the church’s senior pastor since 2013. The clatter of cutlery had yet to fill the room; a listener could have heard a pin drop. "Just take a deep breath. A deep, deep breath, and let it out. Because we can't take for granted any time we've been given."

For some, Dixwell UCC has been a family tradition not just for decades, but generations. In 202 years, thousands of people have passed through its doors, often taking the lessons they have learned with them. The church has birthed activists, abolitionists, barrier-breaking judges, spiritual leaders, lawyers, and politicians. It has become a neighborhood engine, fitting on a stretch of road that also includes the rebuilt Dixwell Community Q House and Varick Memorial Zion AME Church across the street.

Since its founding in 1820 (read that history in full here), it has blazed a path toward social justice. In 1840, congregants and pastor Simeon Jocelyn raised legal funds for enslaved West African captives during the Amistad trials. The church became a stop on the underground railroad, and later opened a learning hub for Black students long before those words entered the modern lexicon. Its leaders supported what would have been the first historically Black college in the country, the creation of the Florence Virtue Homes, and efforts in public health, food security, children’s education, and violence intervention that continue today.

It has moved multiple times, first from Temple Street to 100 Dixwell Ave. in the 1880s, and then to its current home at 217 Dixwell Ave. in 1970. In 1924, the church also donated the land that became the first iteration of the Dixwell Community Q House, now a reopened cornerstone of the neighborhood.

Without the church, there would likely be no memorial to William Lanson, no Dixwell Community Q House, no lovingly-tended tombstone for Helen Eugenia Hagan in Evergreen Cemetery. Its congregants have been keepers of that history.

Around the ballroom, attendees made clear that that history is very much a living one. Stopping every few steps for a hug and warm hello, Bridgeport native Patricia Newton-Foster remembered the first time she stepped foot in Dixwell UCC over two decades ago. While it was initially her late husband Samuel’s church, it soon became her spiritual home.

Over 20 years later, she has become the vice president of the missionary board. The church’s social justice mission has informed her own work running a home care agency.

Top: Patricia Newton-Foster and Dee Marshall. Bottom: Lisa Bellamy Fluker.

As she made her way through a maze of tables, she took time to catch up with Dee Marshall, an educator and champion of Juneteenth celebrations in Connecticut who has attended the church for 35 years. Born in Maryland and raised “all over” while her father was in the military, Marshall remembered first hearing about the church during her years at Texas Christian University. In particular, she was struck by stories of the passionate and driven Rev. Dr. Edwin R. Edmonds, a civil rights activist who transformed the church after his arrival in 1959.

For Marshall, that bent toward social justice was fundamental to finding a church family: she is close with trailblazer Opal Lee, often called the “grandmother of Juneteenth,” and has dedicated decades of her life to education in New Haven. Since coming to New Haven, she’s worn multiple hats in the church—usher, trustee, member of the history and education committees among others. She described it as a large family, connected to a storied and evolving history of Black New Haven.

“We’re able to go in behind all of our ancestors, and to have that crystal bloodline flowing through us,” she said. Speaking at the top of the program, she added that the church’s youngest members will carry on that tradition. “These are our dreamers, who will live out the dreams of our ancestors.”

Wesley Thorpe, Jr., State Rep. Toni Walker, and Angela Thomas. All three grew up in the church.

For her and for many at Saturday’s event, it also marked a chance to remember and celebrate Edmonds, whose 35-year tenure grew the church’s impact across the Dixwell neighborhood. Originally a UCC pastor in Greensboro, North Carolina, Edmonds came to New Haven in 1959 after the Ku Klux Klan threatened his family, including his wife and four young daughters, for his work with the NAACP and civil rights activists across the South. His youngest daughter, now-State Rep. Toni Walker, remembered watching as the white nationalist group killed the family’s dog and burned crosses on their front lawn.

Her mother, a native of Boston, “scooped us up” and headed back to the East Coast, Walker recalled. A fellow UCC minister knew that Dixwell Church was looking for a pastor, and the family ended up in New Haven. For three and a half decades, her father turned the church into a community resource for education, public health, housing and the arts—all of which he saw as basic human rights.

Saturday, she reflected on specific moments that have stayed with her through a career in public service. During his tenure, her father opened a daycare and the celebrated Dixwell Children’s Creative Arts Center while also building housing infrastructure that still exists today. In 1970, he moved the congregation into their current building. In the 1990s, he insisted on opening a space for children with HIV and AIDS, many of whom had been barred from their classrooms.

“All of these things taught me to fight for people who did not have a voice,” Walker said. She remembered walking into the church at just six years old, and hearing Richard Pettaway’s voice fill the whole space with sound. “This is my foundation.”

State Sen. Gary Winfield with his twins, Imani and Gary. While they attend a different church, he said that Dixwell UCC occupies a central place in New Haven history—and his own. "For us, the church is a central part of our lives," he said, tying the work Dixwell UCC does to pushes for police accountability, equitable public education, carceral reform and more. "I'm grateful for a church that gets to be here for 200-plus years."

Beside her, siblings Angela Thomas and Wesley Thorpe, Jr. remembered growing up in the church, where they attended Sunday school classes that turned into decades of worship on Dixwell Avenue. Thomas’ faith carried over into the other areas of her life: she held a career as a social worker for 47 years before recently retiring. Her daughter, Rachele Thomas, is also still active in the church. She still considers it her spiritual home in New Haven.

“It’s spiritual and it carries over into friendships,” she said. A few years ago, she ended up in the hospital miles away from New Haven with a ruptured appendix. During the month that she healed from a hospital room, she received constant calls, cards and well-wishes from members of the church. Her church family showed up.

“I found that really touching,” she said.

Longtime member Sharyn Esdaile, who helped organize Saturday's event, with Charles Warner, Jr., who now serves as church historian.

Longtime member Sharyn Esdaile, who helped organize Saturday's event, with Charles Warner, Jr., who now serves as church historian.

Charles Warner, Jr., who chairs the Connecticut Freedom Trail and became the official church historian this year, also remembered growing up in the church, and returning to it after his studies in sociology at Morehouse University. The middle child of three siblings, Warner looked to Dixwell UCC as “my spiritual foundation,” where he met some of his closest friends and honorary family members.

“I have living examples of success and achievement all around me,” he said. “I’ve sat beside public school administrators, state legislators, the city’s first Black mayor … working with this history is what roped me into active service.”

When he graduated from Morehouse and returned to New Haven, then-historian Margo Johnson Taylor took him under her wing. After years of working “together hand in glove,” she retired during the Covid-19 pandemic. Warner said he is proud to hold the church’s stories—and to share them with New Haven.

Across the ballroom, educator Sean Hardy remembered receiving mentorship from Warner’s parents, Dr. Charles E. Warner and the late Dr. Regina Warner. Both dedicated their lives to the church and to youth in the New Haven Public Schools.

“Polish Your Armor”

“We keep digging up the past in order to polish our armor."

That call to study, learn from, and keep teaching Black history—as part of American history— echoed as journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault took the stage for an afternoon keynote. Moving from her childhood to her college years to her work covering Apartheid in South Africa, Hunter-Gault urged attendees to take what they have learned from the church’s journey—and their own—and use it “to continue to polish your armor.”

She knows something about that armor. Before she was among the students who desegregated the University of Georgia, before she was an award-winning, barrier-breaking Black journalist, before she became a chief international correspondent for NPR and CNN, Hunter-Gault was a “PK”—a preacher’s kid, raised with a sense of moral good that informed her entire career. During a childhood spent between Covington, Georgia and Florida, she learned Bible verses from her grandmother, sometimes while scaling mango trees for the ripening fruit. So when she read about the history of Dixwell UCC, “I knew I had to come,” she said to applause.

Throughout her life, religion has often been her anchor and her guide. She took attendees back to January of 1961, when she and Hamilton Holmes made history as the first two Black students to enroll at the University of Georgia. In the years prior, a team from the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund—led by New Haven’s own Constance Baker Motley—had argued for the students’ right to be there. There she was, finally in her dorm room, when a rock sailed through the window.

Kai Perry, who accepted the award on behalf of the Amistad Committee, Inc. Perry remembered coming aboard on the Schooner Amistad over a decade ago, because she realized that it mattered to have Black people, and particularly Black women, telling the story of the Amistad. As she spoke, she cheered on 100-year-old Al Marder for his work in keeping the committee alive.

Glass shattered over her open suitcase, still laid out on the floor. She could hear the jeers and chants of a crowd beneath her window; she knew that the police were taking their time to show up. And yet, she said, she wasn’t scared. She thought back to her grandmother Alberta Hunter, teaching her verses one by one.

“What she taught me got me through that terrible night,” Hunter-Gault said. “‘Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death’—tear gas and all, that wasn’t in the verse—'I will fear no evil: thou rod and thy staff they comfort me all the days of my life.’ That and other verses Mama Hunter taught me helped me negotiate a road not traveled at that time by any who looked like me.”

She took attendees on a whirlwind trip through her own history, from her mother’s steadfast belief in education to her personal activism to her decades in reporting. As a child in still-segregated Georgia, she saw examples of resilience all around her, from grassroots fundraisers for Black students to her mother’s gentle, quiet encouragement to become a real life Brenda Starr, the comic book reporter with red hair and a knack for a good story.

“From those early years, I was able to keep on keeping on,” she said. Almost three years before she stepped foot on the University of Georgia's campus, Hunter-Gault became part of the case to desegregate the university, watching years of litigation unfold simply so she could go to college. When she finally got there, she said she was unshaken by racial epithets and threats of violence that students—and some adults—hurled at her across campus.

She has kept polishing that armor since, she said. As a Black woman in journalism, she has long been inspired by the nineteenth-century Black journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, and spent years chronicling Black people and Black histories before moving to South Africa. Living there for 17 years, she covered discussions around and the end of Apartheid, creation of a new constitution, and continued economic disenfranchisement of Black people.

Recently, she said, someone asked her why “it was important, in his words, to keep digging up the past.” She didn’t get annoyed or frustrated. She’s been on the planet long enough to know the answer. And at a time when Black history is endangered, criticized, and sometimes forcibly removed from classrooms, it is an answer that may be more pressing than ever.

“We keep digging up the past in order to polish our armor,” she said. “To share the memories—not least as motivation for a new generation, some of whom I see in this room, as they chart their path to the future.”