Culture & Community | Opinion | COVID-19

| From left to right: My uncle Robert, his Nonnie Rose, my grandmother and grandfather. Gellman Family Photos. |

At noon on Tuesday, in a cemetery in St. Louis, five of my relatives buried my grandmother in a tiny graveside service. A global pandemic meant that I wasn’t there. Neither were my parents or my brother.

In an apartment in Minneapolis, my mother stopped what she was doing and sent a few pictures of the old woman, still regal, standing beside a sculpture of interlocking hands. From Brooklyn, my brother sent me a single text: I miss her. Then, not even a minute later, the image of a heart, outlined in black.

In rural Michigan, my dad stepped into his office to take a call from his sister. He could hear a rabbi speaking clearly through the receiver. Birds were chirping.

Is this how we grieve in the age of coronavirus?

Vivian Cecile Gellman—or Nonnie, as I only ever knew her—died in her sleep a week ago, in the early hours of March 20. She was my paternal grandmother, and my last living grandparent. Her death had nothing to do with coronavirus. She was 94—just two months short of her 95th birthday—and had been in hospice for months.

| My partner Tom, me, my dad, and my brother Benji with Nonnie. Elizabeth Sullivan Photo. |

We knew it was coming. Until earlier this month, in fact, we had paid much more attention to her decline and impending death than we had to the spread of coronavirus. We visited in late February, just as the first COVID-19 deaths were reported in Washington, to say our goodbyes. We had a plan in place to return. Or at least we thought we did.

Nonnie was born in May 1925, one of three children in an apartment on Washington Avenue in University City, Missouri. As a young adult, she studied education at Washington University in St. Louis, where she later returned to pursue a master’s degree in teaching. In between, she met and married my grandfather Herman and raised three children, including my father. When she wasn't taking care of her own children, she was looking after others: she was an aunt, a best friend, sharp-tongued confidant, and later a doting grandmother.

She lived her life as an educator. First she taught summer camp, then elementary school, then returned to the university and taught teachers how to teach. She taught family members how to express their love through food, including a brisket that remains legendary in Gellman family lore. She taught herself to care for her loved ones when they were too weak to care for themselves, as she did for her mother Rose and then for my grandfather’s brother, Milton.

She taught my brother and me to entertain ourselves more than once, on family trips that we took while she and my grandfather were still able to travel. She taught me how to make her holiday mix, the corn-starch-splattered recipe card for which is still tucked away in my childhood bedroom.

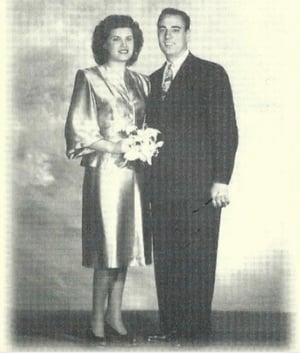

| My grandparents on their wedding day in 1946. Gellman Family Photo. |

When she retired from Washington University in 1991, she taught herself to run a business. She planted her garden, experimented and re-tweaked, and then started to do planting and landscaping in the area. She hired a small staff and filled her basement with thousands of tiny seedlings, nestled beneath heat lamps as they gave off the smell of wet earth. Her principal company, among the hum of heat lamps, was an outdoor cat named after Audrey Hepburn.

By the time I was a small child, she was known affectionately as “The Flower Lady,” a nickname she memorialized with a personalized license plate on her car. Strangers left notes on her front porch, saying they’d been moved by the garden while they were stopped at the lush intersection it touched. Visiting from Detroit, where I grew up, I thought she was a celebrity. Years later, it became my refuge when I returned to the city as a college student.

Even in the last decades of her life, she was vivacious. In the 1990s and into the 2000s, she cooked so much that she joked she ran Cafe Vivienne, home to the finest egg in the basket, steel-cut oatmeal, and poached pears in all of Missouri. When she wasn’t cooking or caring for a family member, she was planting.

She helmed a competitive Mahjong circle on Mondays, where she threw down to defend the honor of First Lady Michelle Obama more than once. She could beat anyone in Solitaire, and often did. When my grandfather began a sharp spiral into dementia ten years ago, she tried to keep a level head.

For the past five and a half years, she lived without him, with increasing help from a series of home health aides. In her final days, she floated in and out of the sharp, sometimes biting wit that so defined her life. She sang Maurice Ravel’s Bolero over the phone with my dad. She talked about her upcoming birthday and how tall my brother had gotten. The last time I saw her, in late February, she told me to plant spinach in my backyard, where a single raised bed is still empty.

There are thousands of stories like this, reserved for family gatherings, sitting shiva, and end-of-life celebrations. There was supposed to be time to share them, after shoveling dirt onto her grave and letting out big, shuddering sobs. But COVID-19 had other plans.

My family unit is spread across four states: Michigan, Minnesota, New York, and Connecticut. On my dad’s side, almost every other relative lives in St. Louis. By last Friday, travel was inadvisable. In Connecticut, Gov. Ned Lamont had all but ordered residents to stay home. In New York City, where my brother lives in a little Brooklyn apartment, cases were exploding.

My parents forbade us from going to the funeral. Then they decided it was too risky for them to go themselves.

But in the absence of our plan—the last-minute plane tickets, frenzied calls to each other, the bittersweet rendez-vous with family at Lambert St. Louis International Airport—we didn’t know what to do. All of the ritual that we’d expected, and that we’d had at my grandfather’s funeral on a boiling August day six years ago, was unimaginable now. There would be a graveside service, and a rabbi would speak for exactly 15 minutes, and we wouldn’t be there.

Instead, we sent text messages. My dad, a doctor who has shaved his beard in case a respirator mask fits better that way, went to work. I took three stories and spent the day talking to drag queens, dancers, and musicians who had all lost their jobs overnight. I fielded questions from my colleagues. I talked to a high schooler who had written an essay on pickling lemons with her grandmother. Nothing stopped. The footprint of COVID-19 grief, which is thick and very real, left no room for us to figure out what to do with our own.

Then, slowly, we managed it. On Friday, we set up a series of four-way conference calls, just to check in on each other. I went to a Zoom Shabbat with a group called Mending Minyan and ugly cried all the way through the Mi Sheberach, the Jewish prayer for healing.

We've talked as a family more in the past week than we have since December. About Nonnie, and about isolation, and about hospital capacity in each of our respective cities. By Sunday, my dad’s younger sister had made sure he’d be able to hear the service. He sent updates from the funeral. We scraped together just enough knowledge on Zoom to hold a functional call, with plans for another.

We realized that in the absence of ritual, we were going to have to create our own. If we didn’t, no one would do it for us.

Dr. Marney White, a clinical psychologist and associate professor of public health at the Yale School of Public Health, said that she recommends setting aside time in a world besieged by COVID-19. Protect your time, she urged me when I called her for a comment on Tuesday afternoon. No one else will.

“I think that one of the most important things that people can do, when faced with significant personal loss in a time of real confusion, is to think about the overall point of the grief ceremonies that we have,” she said. “To that end, try to protect time. Something like a moment of silence, or lighting candles.”

“Something to the extent that virtual connectedness will allow,” she added. “Either an online book or registry … that serves the family a great service. Other things might be to write a letter to the family, or a remembrance. It’s important to protect the time and the ceremony as much as possible.”

I’m writing this—from my dining room table, with a cup of tea—for whoever needs to protect their time. In the past week, a friend of mine posted on social media that her grandmother had died, and she didn’t know how to cope. Another has chosen not to visit his mom at her home, because of what he might be bringing in with him.

There are people across the country don’t know if they’ve said goodbye to a loved one or relative for the last time. There are people across the country who are also saying goodbye virtually, in a way they never thought they'd have to.

The words that strike me, for something like this, belong to Nonnie herself. Like the V'ahavta, I keep running them over and over in my mind.

In 1991, she wrote a letter to my Uncle Robert, the oldest of her three children, and stuck it in an envelope with the words “to be read on my demise.” She lived for three more decades.

“I am continually amazed that no matter what ugliness, sickness, heartache came into my life … they were always outweighed by the good things,” she wrote. “I thank you and the fates and God, and all the remarkable people from all walks of life for my good fortune.”