New Haven Free Public Library | The Hill | Arts, Culture & Community | Elicker Administration | COVID-19

Hopie Chambers, who lives in the Hill on Daggett Street, and Kelly Fitzgerald. Lucy Gellman Photos.

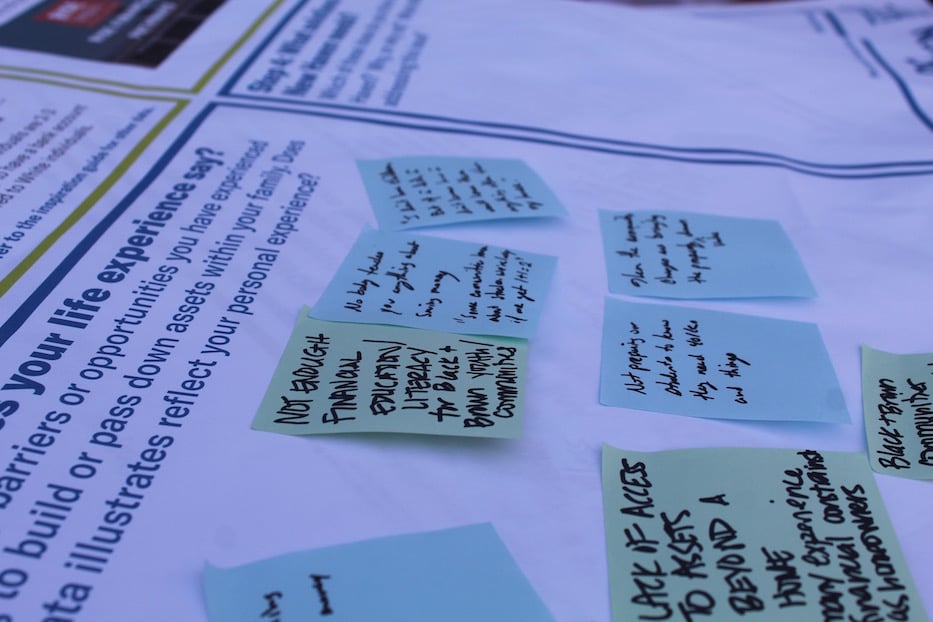

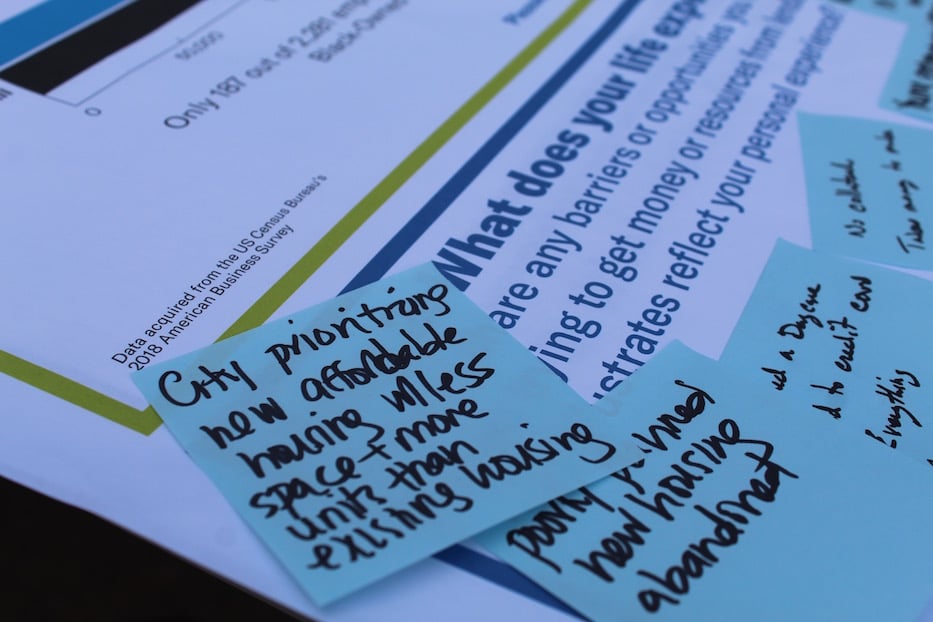

More affordable housing, and ready access to homebuyer programs in all of New Haven’s neighborhoods. Street parking. Safer city blocks and walking beats that look like they did in the 1980s. Financial literacy courses for all of the city’s kids. Grants that get Black- and Latinx-owned businesses off the ground, and then sustain them.

Tuesday, those were just a few of the items Hill neighbors called for at the fourth and penultimate Civic Space session, held outside of Wilson Library in the city's Hill neighborhood. The series is intended to give city residents a say in how the city spends $100 million in federal American Rescue Plan funding. Read more about New Haven’s slice of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan here and here.

“Today’s conversation, I think, is about thinking big,” said Mayor Justin Elicker at the top of the session. “We have over $100 million coming from the federal government to the New Haven community. And that funding can be used over four years to help uplift our community. $100 million is a lot of money, right? It’s a real opportunity. And my hope is that in this conversation that we have today, you think big about what we can accomplish … how can we make four years give back for decades to come?”

Mayor Justin Elicker: "How can we make four years give back for decades to come?”

The sessions are a collaboration among the Elicker Administration, Together New Haven, New York-based consulting firm Hester Street and New Haven based firm DC Design. Since beginning the Civic Space sessions earlier this year, the team has narrowed its focus to the racial wealth gap, with specific attention to homeownership, income inequality, access to institutional capital and intergenerational wealth (or lack thereof) in the city.

It is spearheaded in part by New Haven liaison Corinna Santos, a marketing specialist and small business owner who has done work with the city’s Department of Arts, Culture & Tourism for over a year. In addition to the sessions, which will conclude at the Shubert Theatre Aug. 17, there is an option for New Haveners to submit their ideas, feedback and suggestions online.

At a sun-soaked table on the library’s entrance ramp, Hill residents identified homeownership as the most important topic among them. No sooner had DC Design Founder Durell Coleman handed out fat green stickers than a cluster of lime-colored dots appeared beneath the category.

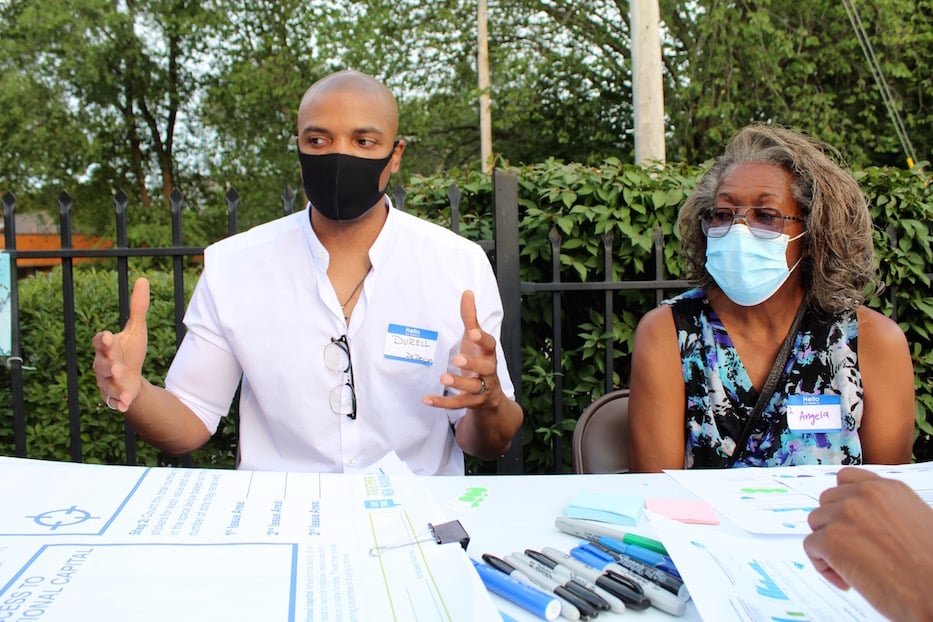

Durell Coleman, founder of DC Design, and Angela Hatley.

Angela Hatley, a military veteran and former owner of a daycare who is now the secretary of the Hill South Community Management Team, said that she’d love to see more easy-to-find assistance programs the city. She reflected on her own time as a homeowner in New Haven, which began 34 years ago in the Hill, and has spanned Gilbert Street to Greenwich Avenue.

Because she struggled through the process on her own, she was excited when she heard about the city's Down Payment/Closing Cost Assistance loan program several years ago. Beside her, Kelly Fitzgerald suggested that every realtor and mortgage broker make it part of their pitch to potential homebuyers. Fitzgerald is the senior director of financial stability at the United Way of Greater New Haven.

"I did it the hard way," Hatley said. "When I heard that there were programs in place to help people with deposits and things, I thought that was a great thing. That's more than I ever got."

"Yes!" echoed Roni Elliott, who bought a home in the Hill 32 years ago. "It was old school when I got mine.”

Coleman saw it as an opening to imagine new types of assistance. He pointed to the HouseHartford Homebuyer Assistance Program, which gives Hartford-based homebuyers up to $40,000 in financial assistance to buy one- to four-family homes. Beside it, there was a graphic for Home First, a down payment assistance program through the New York City Department of Housing.

“That is good,” said Elliott of HouseHartford. She added that she’d like to see more affordable housing that isn’t controlled by mega-landlords, particularly Mandy Management. In the past decade or so, the company and its affiliate holdings have developed an outsized presence in the neighborhood. She advocated for more owner-occupants and single-family homes.

“We get to dream here,” Coleman said. “We get to think about what that could look like.”

It's not just homeownership, longtime Hill resident Johnny Dye said—it's also the relative safety of a neighborhood. In over six decades of living in the Hill, he's watched it go from a self-sustaining, diverse and tight-knit section of the city to one that is too often singled out for its violence. When his 32-year-old granddaughter visits from Baltimore, he asks her to tell him exactly where she's going and stay indoors most of the time.

With others at the table, he advocated for a return to community policing, which was on its way out before Covid-19 and has since become a casualty of the pandemic. Elliott suggested a return to walking beats and new training methods that focused on a given neighborhood's needs. Those were commonplace back in the 1990s, when Nick Pastore and K.D. Codish shook up the department with interactive theater, peer-led arts programming and specialized training around sexual violence and public health.

“There’s been such a drastic change,” he said. “Roni [Elliott] can tell you, and Angela can tell you, we left our doors open. Now we have to have ring alerts on ‘em. Now, I’m afraid for the kids down the street.”

Johnny Dye, who has lived in the Hill for over 60 years.

Hatley said she’s frustrated at the Hill’s location as something of a dumping ground for social services in New Haven. The neighborhood is home to not only Yale New Haven Hospital—which has taken away homes and businesses, she said—but also several shelters, the Connecticut Mental Health Center, and the APT Foundation. She proposed a more equitable distribution of services across the city and the region, including those that address substance use disorder and chronic housing insecurity.

She also questioned whether the city is genuinely ready to listen to residents of the Hill, which is New Haven’s largest and most diverse neighborhood. Often, she finds herself feeling like the city asks for input, and then ignores what residents have to say. She pointed to a concurrent meeting of the New Haven Board of Alders Legislation Committee, in which alders were voting on proposed zoning changes that would allow for accessory dwelling units (ADUs), The ADUs do not include parking.

“It’s a challenge living here, and you want to be able to have people come to see you without thinking the worst,” she said. “What we desire? We want a livable community. And that encompasses so many aspects of what we’re discussing tonight.”

Emiliano Campos, who is a student at Eastern Connecticut State University.

It led the group straight into a discussion of small business support and access to institutional capital, from financial literacy courses to grants to inherited wealth. Coleman noted that fewer than 200 of 2,281 New Haven employers surveyed are Black- and Latinx owned, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2018 American Business Bureau Survey. Both Hatley and Dye attributed some of that to urban renewal, which gutted Black-owned business districts and razed homes as developers made way for the highway.

Dye recalled how vibrant Congress, Washington, and Dixwell Avenues used to be before the 1960s. He turned back the clock to a time when those streets teemed with stores and homes. He said he still thinks about The Monterey, a storied jazz club on Dixwell Avenue. For Hatley, it’s still hard to walk by a once-dense Gilbert Street and see Yale New Haven Hospital in its place.

“Whole swaths of the neighborhood,” Hatley said. “Blocks and blocks. Houses. Just destroyed. These were homes. This was a community. We didn’t have to lock our doors. We had families that knew each other, that owned these homes and things. The city knew better. They come here telling us what’s good for us, and knocked everybody’s houses down. What stands there now?”

Patrice Edwards, a project associate with Hester Street, and Durell Coleman.

Coleman drew the group’s attention to the NC Idea Micro Program, a grantmaking program based in North Carolina that awards up to $10,000 to businesses that are getting up the ground. Hatley suggested giving direct support to small New Haven nonprofits including Collab, a business incubator with a focus on women and members of the global majority.

Emiliano Campos, a New Haven Promise intern who is currently a student at Eastern Connecticut State University, piped up from his chair. In the past year, he said, he’s heard about cities that are re-granting American Rescue Plan funds to small businesses, rather than offering loans like the Paycheck Protection Program.

“It doesn’t have as much of an effect on the actual business, cause they don’t have to pay it back,” he said. “You get to support the actual business. Just throwing that out there.”

Coleman said that that resonated with him as a small business owner. For the first decade of his career running DC Design, he didn’t take a single loan because he was worried about paying it back. It took the uncertainty of the pandemic to push him towards one.

Both Hatley and Elliott told the group that they’d love to see courses where New Haven Public Schools students were able to learn about credit, building savings, wealth management. Coleman noted that millennials—of whom he is one—struggle to save because of the sheer cost of living in New Haven.

During the pandemic, that has become particularly true as students take on one or multiple jobs to support their families while juggling classes, taking care of their siblings, and caring for family members who may face unemployment or health concerns.

“Nobody teaches you anything,” Hatley said. “Certain communities, in school, they have things about stocks. In our community, we’re good if we get one and one is two!”

She and Fitzgerald advocated for classes that teach students how to budget, build savings, and balance their checkbooks. She also acknowledged that the sheer expense of living in New Haven makes it nearly impossible to save money and build wealth in New Haven.

She asked aloud what it would look like for students to learn what a 401k is early on—and for residents to make more, or have a lower cost of living. On a page in front of her, a blurb on the Magnolia Mother’s Trust, which supports Black Mississippi mothers living in poverty, seemed to suggest possibility.

“It’s tied to people having enough income that they can pay their bills and put something aside,” Fitzgerald said. “If you’re aways living paycheck to paycheck and that little bit of emergency fund you have goes to when your car breaks down. People need to be able to earn more money to be able to do these things.”

The final Civic Space session is scheduled for August 17 at the Shubert Theatre in downtown New Haven. Learn more and submit ideas online here.