Dixwell | Movies | Arts & Culture | Film & Video | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism | Black Haven

Actor Sinque Tavares was all jitters, pacing as he waited for the news on a lease. Behind him, a squat Meriden apartment complex peeked out across an expanse of dirt and grass. Midday traffic passed by, humming its urban lullaby. Then the phone rang, clear as a bell. The camera did a close pan on Tavares' face. A beat dropped, and he was moving through space, his body a live wire.

Somewhere outside the frame, filmmaker Gerald Lovelace had found the perfect shot. And he was just getting started.

Saturday night, five Connecticut filmmakers brought that cinematic swerve to the second annual Black Haven Film Festival, held in the parking lot of Dixwell Plaza with a virtual component for those watching at home. After a year entirely online, the team set up the event as a drive-in movie theater, with a large inflatable screen, limited number of outdoor seats, and radio station carrying the sound of each film.

By the end of the night, it became a study in the explosive power of Black joy, creativity, and collective memory. Filmmakers included Brennan Maine, Kolton Harris, Jefferey Dobbs, Karl D. Gray Jr. and Lovelace. In addition, the festival featured performances from New Haven musician Tyler Jenkins and poet Weruché George, a writer, Nigerian immigrant, and commissioner on Hamden’s Commission on Human Rights and Relations. In all, over 160 viewers attended.

Black Haven Founder and Creative Director Salwa Abdussabur. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Black Haven Founder and Creative Director Salwa Abdussabur. Lucy Gellman Photo.

“I’m so excited for you to see this,” said Creative Director Salwa Abdussabur, who founded the festival last year under the umbrella of the Black Infinity Collective. “It’s so amazing to see this manifest before my eyes.”

This year, Black Haven focused on the theme “Blackness Is Global,” with a particular nod to visual storytelling across generations and sometimes beyond the veil. From the moment that Maine’s 2016 Skin began to play, attendees in the parking lot fell to a hush, the light of the film making the parking lot glow. On screen, two arms reached around the torso from which they sprouted, fingers working their way across a sea of black skin.

Knuckles bent, lovingly kneading handfuls of skin. Low sax hummed somewhere in the distance. The frame shifted to a pair of lips, shining in dark matte lipstick. They belonged to poet and writer Angela Adusah, who wrote, directed first performed in the work five years ago. Even as cars zoomed by nearby on Goffe Street and Dixwell Avenue, the parking lot was quiet, reverent.

“My Black is the largest organ on my body,” read Adusah. Maine’s color grade made her skin glow gold. Through the lens, the filmmaker focused on the breath, spit-kissed air and distance between teeth and lips, a half moon of nose ring.

The scene shifted, and suddenly Adusah was in profile, her face at the far right of the screen against an expanse of grey-black. A wisp of hair hung by her left cheek, more of a suggestion than a halo. Her mouth moved, and in it she held the whole universe in it for a moment.

“Without it, I lose to your cold stony words and never ending medical terms” she said. “I hold no statue without my Black/for my Black/Holds me together.”

In their cars and a small seated audience, viewers watched closely as Maine shifted the angle again and again, slowly revealing shoulders, flexed fingers, skin stretched taut over clavicles. Adusah’s words fell quickly, sharp and deliberate. The more Maine shifted the camerawork, the more of Adusah’s face and mouth a viewer got to see as they listened. Both she and Maine made it clear: in every dimension she was indisputably Black.

The performance became a study in the weight of her language, words wielded with great care. At one point, they stopped altogether and the poet looked out at the camera, blinking in slow motion as music built beneath her. At another, Adusah’s lips trembled on the final lines. Maine lingered on her mouth, marvelling at its power. In the audience, a few drivers honked their horns to show applause. Skin later won first place in the festival.

As the festival cycled through films, artists danced, sang, spoke and animated their way through the multiplicity of a diaspora. Based on the same track on the musician’s 2020 EP 4 Freedom, Harris’ music video Black Joy brought viewers into a school, where a white educator admonished a room of Black students in detention. Phrases including I am here because I did not make good choices were scrawled across the board. At the beginning of the film, the camera lingered on a single student, watching her take a long, slow breath before entering the room.

Inside, the teacher loomed over students, her eyes menacing. Then Harris walked through the halls, turned the door handle, and entered the classroom.

On screen, the magic of his presence whisked her away, like a Wizard of Oz built specifically to deal with the petty tyranny of power-tripping white educators (a few cheers rippled through the outdoor audience). He wrote the words Black Joy on the board and began to move when students’ expressions came up blank. Suddenly, the room was in motion. His lyrics buzzed around them, lifting the classroom off its dreary axis. The lyrics did the rest of the talking.

All this melanin, it’s a gift/From the God who made the earth

If you think/It makes us less/Check your thinking/You’re absurd

All my brothers/All my sisters/Check the mirror/Know your worth

Keep your eyes on the prize/No more false advertisements

In a system where white educators still outnumber their Black and Brown students in schools across the state, the result was so exuberant that it was hard to stay still in the audience. Dancing with students down the hallway, on cafeteria tables, and in classrooms, Harris traded a white fetish for Black trauma and pain for an unbridled, hard-fought, entirely danceable kind of joy. It doubled as a call to arms—against white supremacy, and towards liberation.

That joy flowed through Dobbs’ Synesth-Sense, an animated short completed as the filmmaker’s senior project at the University of Connecticut last year. As the work opened, a few murmurs went up from the crowd at a familiar site: an animated facsimile of Coogan Pavilion, which sits in Edgewood Park in the city’s Westville neighborhood. On screen, Dobbs’ protagonist stood larger-than-life before a blank wall, gripped with indecision. Around him, the world faded to grayscale—until he spotted a radio and turned it on.

Bursts of color flooded the frame, then disappeared as the music faded. Dobbs’ character switched the channel, and paint-like pops of color filled the world once more. They pulsated, round and raindrop-like, then flew through the air. They swirled around the park, soaking it in pinks, greens, and blues. When the radio fell from his hand, he took a beat and listened. Music emerged from the earth around him: whispering skateboards, chirping birds, breathy graffiti cans. Everything he needed to was right there.

“The change I want to see in the world is being able to be yourself,” Dobbs said in a video before the film. It seemed he had arrived.

Karl D. Gray Jr.’s Post[Humous] Pops & Live Son. Lucy Gellman Photo.

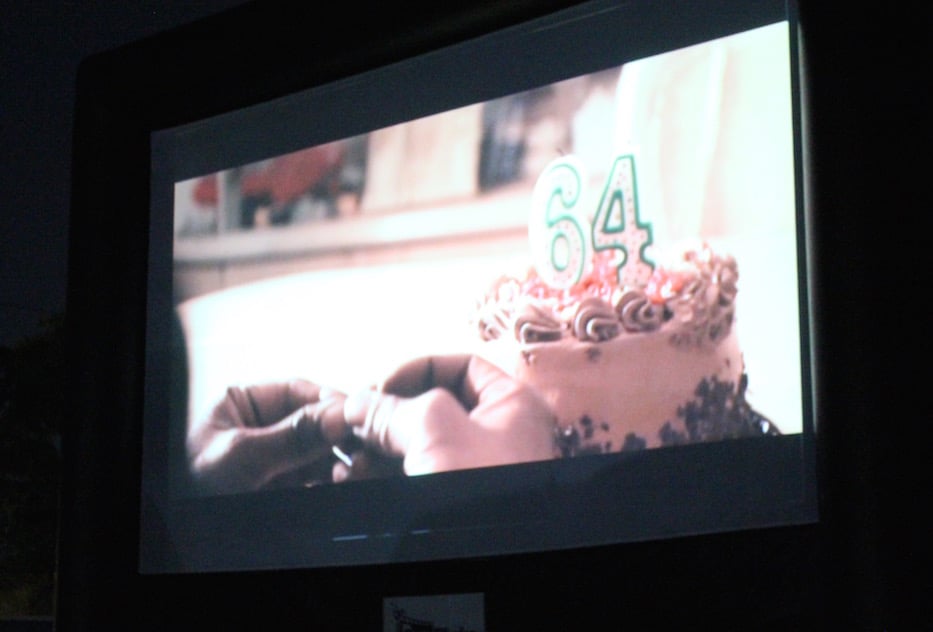

Other filmmakers focused on the shared, sometimes strange intimacy of grief. In Karl D. Gray Jr.’s Post[Humous] Pops & Live Son, the filmmaker invited viewers into his own home, where he unboxed a chocolate birthday cake for his father’s 64th year. In the background, a wispy, muscled version of “Happy Birthday” floated through the house’s empty spaces (credit to Willa M. Gray, or as the filmmaker credited her, Mommy), keeping Karl, Sr. alive in its nooks and crannies.

In the parking lot behind Dixwell Plaza, time seemed to slow down. Gray moved through it with a ceremony of absence: his hands on the scalloped, plastic covering of the cake, the ribbons of untouched chocolate frosting, the empty chair in front of him and empty couch in the background. He pressed colorful wax candles into the cake. As the frame jumped between his face, the empty chair and lived-in cabinets, he began to speak to his father, who died in July 2019. As viewers watched, it became easy to see the spirit world as not so far away, with ancestors peeking down to check in.

A different, far less understated kind of celebration defined Lovelace’s This Day, a musical concept video inspired by the eponymous track in the 2020 Christmas movie Jingle Jangle. In the video—likely relatable to many of the artists watching in the parking lot and at home—a Black creative wants to open his own space. When he gets the call that his lease has been approved, he springs into song and dance, marrying something that lives between Hamilton, In The Heights, and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. As he flows through Meriden’s streets and public parks with fellow dancers, it becomes a sort of pact that their creativity will be enough.

The trick, of course, is that Lovelace takes the rarity of these beautiful, not-entirely-lily-white bodies dancing together and makes it feel like something viewers should never live without. He argues that it should be the rule, and not the exception. In just over five minutes, he also shows off his skills as a cinematographer, alternating between close shots, tight, clean indoor and outdoor frames, and a few drone shots from above. It is also Lovelace’s own story: he is a filmmaker, choreographer, and owner of The Lab, a creative space in Meriden.

“Blackness and Black Identity is a global experience, rich with culture and generational storytelling that ornate who we are and where we have been,” Abdussabur said. “Our Blackness influences our art, ignites our activism and helps us imagine an Afro-futuristic world. Tonight we are living Black art.”

Find out more about Black Haven at their website.