City-Wide Open Studios | Arts & Culture | New Haven | Visual Arts

| Artist Isaac Bloodworth: “It kind of put me in the role, whether I wanted it or not, of being the social person and talking about the issues that I may be going through." Lucy Gellman Photos. |

This is an installment in an ongoing collaboration with The Lineage Group highlighting artists of color in the New Haven region. All of the artists featured are members of the group's Rev.A.A.R.T.lution series.

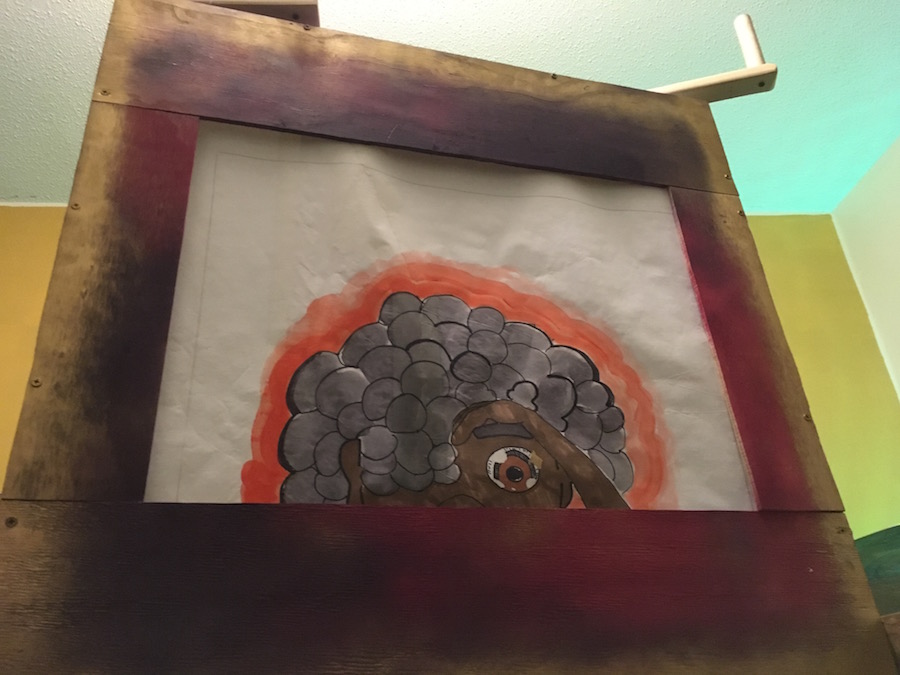

Isaac Bloodworth disappeared behind a wooden frame and began cranking. On cue, a little boy named Joy tumbled through his childhood, buoyant and playful. Head of wooly, black hair and eyes that shone bright as they took in the world around him. Joy chased butterflies in the yard. Joy walked down the sidewalk with a spring in his step. Joy bought a pack of skittles from the corner store.

By the end of the performance, Joy would be dead at the hands of police officers. Miles Davis’ “Freddy Freeloader” coasted over the room.

“His favorite thing to do was go outside and chase butterflies all day,” Bloodworth read from behind the screen as audience members leaned in and held their breath. “It always seemed to bring him on an adventure.”

Bloodworth is a recent graduate of the University of Connecticut’s puppet arts program, dedicating his nascent career to work about being Black and male in America. This weekend, he will appear as one of the artists in Urban Perspective: Black Minds Rewired, a City-Wide Open Studios (CWOS) commission and performance geared toward mental health in the Black community. In addition to Artspace New Haven, support for Urban Perspective comes from the National Endowment for the Arts, and the CT Office of the Arts.

“My work is about what best way to tell my single experience as a Black man, and the things I’ve been through,” he said in an interview Wednesday afternoon. “Mental health is a relatively new thing for me.”

The two-minute CWOS performance, which he is keeping under wraps for Saturday and Sunday, is titled “Beautiful Crown Bright Mind.” But long before he had jumped into that project, Bloodworth was born and raised in New Haven’s Edgewood neighborhood, hooked on art and design from the moment he entered his kindergarten classroom.

At first, doodles of dinosaurs, animals and fantastical creatures populated his pages. He loved superheroes, saving his weekends for trips to the Chapel Street comic book shop Alternate Universe, early-morning Saturday cartoons, and VHS tapes on Anime and Rugrats.

Art surrounded him at home. His father Earl Bloodworth, program manager for the city’s Warren Kimbro Reentry Project, is also a writer and poet whose work includes a trove of love letters he composed to Bloodworth’s mom. His mom, a doctor who immigrated from Jamaica, “is more of a math and science person,” but likes to draw. An only child, Bloodworth said he turned to his designs to keep himself occupied, watching as his parents slowly warmed to the idea that he wanted to do art for the rest of his life.

But puppets did not interest him initially. As a kid, Bloodworth wanted to be a magician-golfer, pulling tricks out of thin air while also quashing his opponents on the course. Until, that is, he realized he didn’t especially like golf—or magic.

“Magic isn’t real the way I thought it was,” he said. “It’s still real, just not the way I thought it was. There’s a lot of science and math that goes into making illusions.”

Still, art tugged at Bloodworth’s interests. As a kid, he watched his mom train to become a pediatric nephrologist, certain that he didn’t want to follow in her footsteps as she completed her residency and fellowship years. He watched her experience loss, sometimes with very young patients whose kidneys failed them. He didn’t have the same tolerance for that, he said. So he kept drawing instead.

When he was in middle school, his parents put him into Achievement First Amistad Academy, where he got in trouble for drawing during classes and was ordered to cut his afro off, because “it was a distraction to the class, apparently.” But instead of giving up his craft, he dug in further (“I could get in trouble for it and still get good grades,” he laughed). He started carrying a sketchbook around with him, his mom protesting when he tried to bring it into medical events and shops around town, and his dad convincing her that it was okay to let him do his thing.

“It’s kind of funny—I would take my sketchbook everywhere,” he recalled. “It was just a part of me … either loose leaf paper or sketchbooks, because sketchbooks were expensive to buy on my own.”

In eighth grade, Bloodworth got news that he’d been accepted into Cooperative Arts & Humanities Magnet High School (Co-Op), where he doubled down on a visual arts concentration. There, he nurtured an interest in not just drawing but stop-motion animation, entranced by Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas and Henry Selick’s Coraline. He added theater to his wheelhouse, ultimately snagging a role in the school’s rendition of The Drowsy Chaperone that made him realize that “I wanted to do all art.”

Over the summers, he enrolled in high school enrichment programs offered across the city and state, taking a mix of advanced classes and arts programming. One of them, the now-discontinued UConn Mentor Connection, offered him the chance to live on UConn’s campus for three weeks, and see what it might be like to be a college student there. Bloodworth was 16 and “knew I wanted to do something artsy that summer.” The only option was something called puppet arts. He didn’t know exactly what it was, but signed up anyway.

When Bloodworth arrived, he heard Puppet Arts Program Director Bart Roccoberton speak about “tons of business opportunities and job opportunities” in the field of puppet arts. Just a few days into a summer program, he was hooked.

“I didn’t want to pigeonhole myself to just one thing,” he recalled. “And puppet arts does that. You get to perform, you get to build, you get to draw, you get to paint, you get to sculpt, and plan and all these other things. I think that’s why eventually I picked puppet arts.”

As Bloodworth approached his senior year at Co-Op, he applied to the puppet arts program, getting in the spring of his senior year. But when he returned to the university’s sprawling and picturesque campus in Storrs, he found that it seemed really white. Really, really white. In his cohort of 24 students, there were three people of color. He was one of them, becoming fast friends with two Latino students also in the program.

“Visually, I think I was the most prominent minority,” he said. “It kind of put me in the role, whether I wanted it or not, of being the social person and talking about the issues that I may be going through.”

As he eased into classes, he discovered that several of his peers hadn’t spent time with people of color, and had “a lot of questions, misinformation, and sometimes ignorance” about his lived experience and systems of racial power and privilege as they played out across the state, and across the country. But as he “burst the bubble for them,” he also learned a lot about his own upbringing—and how fellow college students, most of them white, thought about race.

Those crystallizing moments took place in and outside of the classroom. Early into his studies, Bloodworth found himself defending scholarships specifically for students of color, which several of his peers referred to as a form of “discrimination” against white people. He took a class where a professor taught students how to apply skin tone to puppets, but only supplied Caucasian-looking options until Bloodworth spoke up at the end of class. Or another in which the instructor touched his hair, for which she apologized two years later after reading an article.

His junior year, Bloodworth said he made a conscious decision to “start learning more, and being invested more in my culture and my history.” His sophomore year, he’d taken classes in Caribbean history and African-American literature, finishing out the year with an explosive puppet presentation on Rafael Trujillo’s reign in the Dominican Republic. He dug into African-American theater, praising a white professor for holding herself accountable as she taught the class about titles Bloodworth had never heard before.

But it was also the year that a classmate hurled a racial slur right at him, yelling “the N word” across campus. He started working towards projects that had Black characters and Afrocentric themes at their core, scored with jazz, Nina Simone, Billie Holiday and Kendrick Lamar.

“I realized I'm not a protester—it brings a lot of anxiety and also fear of safety,” he said. “But I realize my art can be the way. Also because art lasts so long, and history can get jumbled. But the art doesn’t really get jumbled … the art kind of stays consistent. Especially if you put your mark on it.”

As he worked through his studies at UConn, Bloodworth also became involved with New Haven Promise, spending multiple summers at the Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG). Even now, he said, he takes refuge in the modern and contemporary galleries at YUAG, where works by several artists of color hang on the walls. He praised local artist and MacArthur genius Titus Kaphar, who he said he wants to get to know better.

But he couldn’t—and still can’t—walk through the European art section without his skin crawling. He started to speak candidly about racism at the gallery at the end of his internship term. There weren’t a lot of people who looked like him, he said at a staff meeting where New Haven Promise students were asked to speak. That wasn’t okay.

“The walls that we built up here physically and emotionally kind of build a barrier against the community, and we have to work against our biases,” he recalled saying. “I wasn’t looking for praise. I just want you guys [folks at the gallery] to look at the way you uphold systems of racism.”

When he graduated, he returned to New Haven, working at Long Wharf Theatre and then the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA). While working at the second, he grew interested in museum work, and the possibility of bringing more art forms into galleries.

“Being in these institutions has been really weird, especially during my awakening,” he said. “Not being woke, but just awakening of knowledge.”

Bloodworth said that focus on representation—people of color and LGBTQ and non-binary folks in particular—now drives his work. In the past several months, he has been working specifically on designs and “crankies,” or moving displays, that revolve around and lift up women of color, including a collaboration titled “Curled,” which is “pretty much the Black version of tangled.”

He’s also working on his Metamorphosis series and a project titled “The New Minstrel Show.” And bringing work like Metamorphosis I, centered on a Black boy named Joy, into community spaces like Sofar Sounds New Haven.

“I’m trying to get people to change the way they see things in different aspects by talking to people,” he said. “Just finding conversations, finding people to talk to where I can bring these issues to the front. ”

“Realizing I’m in these spaces, and it’s not just to get money, and it’s not just to sit there in the office,” he said. “It’s also to tackle the issues that the university or institution has had by my art, and all these other conversations I have on a daily basis.”