Downtown | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Yale University | COVID-19

Lucy Gellman Photos.

Buckets of blue and teal paint dotted Prospect Street, glistening in the sunlight. McFadden & Whitehead’s “Ain’t No Stoppin' Us Now” pumped through the speakers. Halfway down the street, Celesta Kearney and her niece Amari dipped their rollers in paint and danced to the music. At the intersection of Prospect and Grove Streets, New Haven Rising Director Scott Marks picked up a mic.

“When I say Yale, you say ‘Respect New Haven!’” he yelled.

Saturday, over 150 union members, organizers, grad students, Yale employees and townies came out to paint Prospect Street with the words “Yale: Respect New Haven,” a slogan that has become synonymous with a call for Yale to increase its voluntary contribution to the city and make good on its promise to hire locally, particularly from the city's poorest and most chronically under-resourced neighborhoods. The event was organized by New Haven Rising and Unite Here-Local 34, the union that represents Yale University’s clerical and technical workers.

Top: Midway through morning painting. Bottom: Hunter Ian Cupo Dunn gets in on the painting action with his grandfather Mike and dad Ian Dunn.

The event comes before a May 5 car caravan and rally this week, at which union members will be making the same demands. Currently, over 40 percent of the city’s tax-exempt properties are owned by Yale University and Yale New Haven Health. According to Local 34, that translates to a tax break of over $157 million dollars per year. While the city is projecting a $66 million deficit, Yale has also reported a $203 million surplus. Its endowment is currently $31.2 billion.

“Yale needs to invest more in the city,” said Hill Alder Ron Hurt, who is also an organizer with New Haven Rising. “I live in the shadow of Yale New Haven Hospital. Children in my community, 30 percent of them go to sleep hungry. So I’m here to send a message to Yale to respect New Haven.”

Around him, attendees trickled in and picked up brushes and rollers. Along one side of Prospect Street, a three and one-quarter inch red rectangle depicted Yale’s current $13 million voluntary contribution to the city. Beside it, a 670-foot contiguous blue stripe represented the university's $31.2 billion endowment. By 10 a.m., it stretched all the way to Trumbull Street like a long, lolling blue tongue.

Working on a section of the line beside the Becton Engineering and Applied Science Center, Anita Dunn and Kuli Baro both said they’d come out to help. Baro, who lives downtown, does not work for Yale but hears about the university from friends that do. Dunn, whose son is union spokesperson Ian Dunn, worked for several years as a physician’s assistant at Yale New Haven Hospital. Saturday, she was deputized as both a painter and babysitter for her grandson, Hunter Ian Cupo Dunn.

Top: Anita Dunn and Kuli Baro. Bottom: Dunn works on the start of a line depicting Yale's $31.11 billion endowment.

In her previous homes of Minneapolis and Tucson—both home to large public, land grant universities—she said that she saw a more demonstrated commitment from institutions to supporting both the local economy and local jobs. The University of Minnesota, for instance, reported over $343.4 million in “direct and indirect/induced tax payments” to state and municipal governments in Minnesota in 2017. While Yale is a private university, she argued that its finances allow it to contribute more to the city each year than it currently does.

“The university has an obligation,” she said. “Yale is a major internationally recognized university. This small Connecticut city that supports Yale doesn’t get nearly as much in return.”

At a greeting table, 16-year-old Manuel Camacho said that he’d come out to demand jobs for members of the New Haven community who are battling unemployment, food insecurity, and gun violence in addition to Covid-19. One day out from his second vaccine, he joked that he was pushing through side effects because “there is more work to do.”

Growing up in Fair Haven, Camacho heard stories from his grandmother about how Yale became an economic lifeline when it hired her as a maintenance worker in the 1980s. Then in the 1990s, she was laid off. She never got her job back, and struggled to find work. He said his cousins have been applying to the university for years with no luck. Meanwhile, he has watched his family’s rent rise each year.

Top: Manuel Camacho and his younger brother work on the message.

Now a sophomore at James Hillhouse High School and Latino Caucus President for the youth anti-violence group Ice the Beef, he said he thinks constantly about what New Haven’s resource-strapped communities could do with more funding from the university. He looked to a recent groundbreaking at Goffe Street Park as an example and said he would like to see the same effort replicated in Newhallville, Fair Haven, and the Hill. With Citywide Youth Coalition member Mellody Massaquoi, he later dropped off a “Yale: Respect New Haven” petition to University President Peter Salovey.

“It’s simply a matter of the right thing to do,” he said. “Often these corporations hire people from outside the city. I feel we should hire local residents. I see how much of a struggle it is to live here … and I think about how much we could get done [with more resources]. We could start to clean up the city.”

Down the block, Kearney steadied a teal-soaked roller and inspected her work. A senior administrative assistant at Yale University Orthopaedics, she lives in the city’s Newhallville neighborhood with other members of her family and her 12-year-old niece, Amari.

All around her, Kearney sees a city where “the streets need paving, the schools need help,” and youth have very few places to go outside of school. Amari often complains that she feels stuck inside the house after her classes at Elm City Middle School are done for the day.

Top: Celesta Kearney. Bottom: her 12-year-old niece Amari.

While Kearney is excited for the new Dixwell Avenue Q House to open this summer, she said that she would like to see more accessible after-school programs and opportunities for youth across the city. Years ago, Amari participated in a theater camp that she loved. Since, she hasn’t been able to plug into anything similar. The 12-year-old added that she’d love more funding for school libraries and books that she could read throughout the school day.

“I feel like she has nowhere to go,” Kearney said as she and Amari laid down another coat of paint. “Especially at a time like this, you [Yale] should be giving more.”

New Haven Rising organizer Jaime Myers-McPhail said that he also wants to see more resources for young people in the city. Born in New Hampshire, Myers-McPhail grew up in a poor community, and sometimes felt so hopeless as a kid that “there were times I didn’t see myself making it to my twenty-first birthday.”

In Connecticut, he’s acutely aware of the wealth gap that exists between wealthy, largely white suburban towns like Greenwich and Woodbridge and majority nonwhite cities like New Haven. Before his stepson graduated from the city’s public schools, Myers-McPhail watched him struggle to get the individualized attention in the classroom that he needed. Recently, he spoke to a young New Havener who felt that his best option after high school was to join the army.

Myers-McPhail said he believes that more economic and professional resources would translate to more opportunities for young people. He has calculated that his share of Yale’s “tax break” is more than an extra $2,400 that he pays each year.

“What you see when you’re out in the suburbs—our young people cannot even fathom that,” he said.

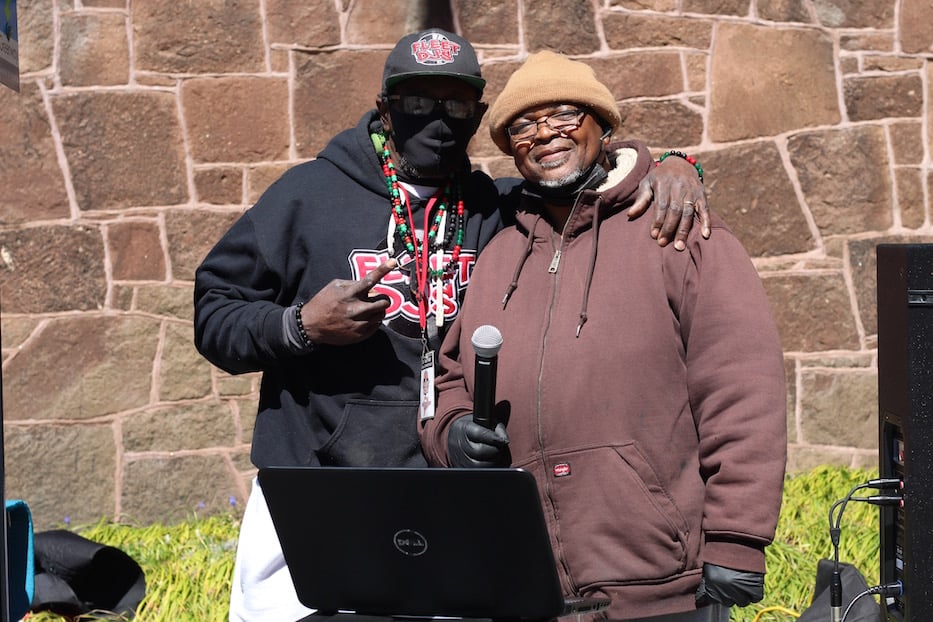

Top: New Haven Rising organizer Jaime Myers-McPhail. Bottom: Mike and Raydell Battle (a.k.a. DJ Crazy Ray).

Back at Prospect and Grove Streets Mike and Raydell Battle (a.k.a. DJ Crazy Ray) spun a steady mix of Marvin Gaye, Earth, Wind & Fire, Teddy Pendergrass, and the Isley Brothers. After an initial concern that the blustery morning might detract from the music, the two slid into a familiar rhythm. Motown and R&B crackled to life in the shadow of Woolsey Hall, where Yale once threatened the New Haven Symphony Orchestra into opposing legislation that would have challenged its tax exempt status.

“It’s something I like to get involved in,” said DJ Crazy Ray. “I’m out here for the cause, and for the community. As we say, it takes a village.”

Marks paced up and down the street behind them, stopping to explain the long blue line to a film crew that had showed up. As they parked their cameras in front of him, he pointed to the entirety of the street and said that he hopes Salovey thinks of “the black line”—the $203 million surplus that Yale reported in November—that the university could pour into the community without touching its endowment.

“I would want him to look at this line and feel shame,” he said.

For more coverage of the day and Yale's response, check out this article from our colleagues at the New Haven Independent.