Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19 | Libraries

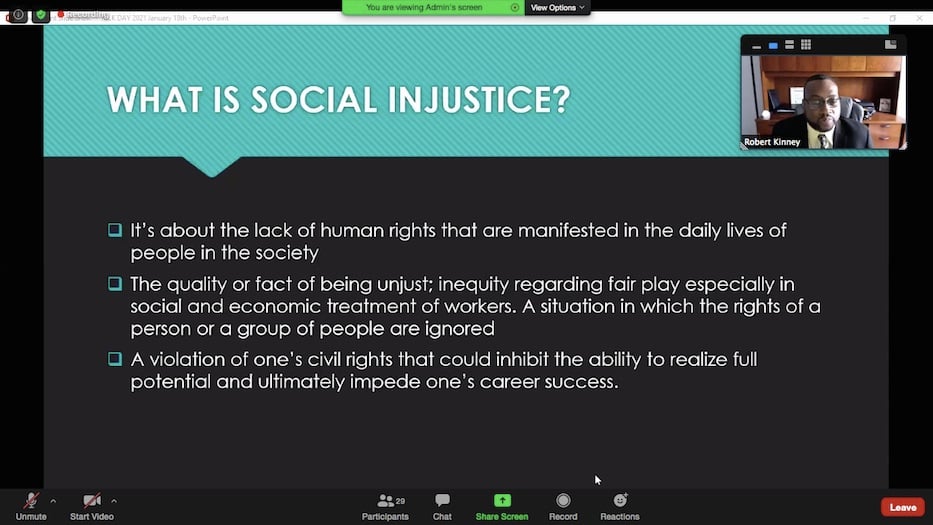

Robert Kinney kicks off the discussion. In addition to his work for the Connecticut State Library, he is a pastor at Mount Hope Temple Church in New Haven. Screenshot from Zoom.

One librarian made sure that a family had food, and an extra helping of community support. Another watched and learned as a Hartford bookmobile added canned goods to its roster of circulating titles. A third stood inside a New Haven branch library, making sure bags of children’s books were ready for distribution in the community.

From Zoom to Dixwell Avenue to the Hill, several of Connecticut’s Black librarians spent Monday reflecting on how, over half a century after his death, Dr. Martin Luther King’s words still provide a blueprint for community engagement and activism in their work. This year, the holiday comes as libraries across the state are stretched as social service providers in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Had he not been assassinated 53 years ago this April, King would have celebrated his 92nd birthday earlier this month.

On Zoom, members of the Connecticut chapter of the Black Caucus of the American Library Association (BCALA-CT) gathered to discuss how King’s words sit with them as they work to serve community member across the state. The talk was part of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History’s 25th annual celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., moved online due to Covid-19. A full lineup of recorded events is on the Peabody's Facebook page.

Elise Browne, a library technician at Eastern Connecticut State University (ECSU).

“Librarians are educators,” said Elise Browne, a library technician at Eastern Connecticut State University (ECSU) and secretary of BCALA-CT. “We are aware of the resources that are vastly available in our libraries. We really want to empower the community with all the resources we have at our disposal.”

One after another, panelists spoke on King’s legacy as a call to empower and support the communities that they are in, and particularly communities where patrons may look like them or share lived experience. BCALA-CT President Robert Kinney, outreach services librarian at the Connecticut State Library, said he returns to King’s words on self-love and community stewardship when thinking about his own style of leadership. It's one that he also brings to Mount Hope Temple Church in New Haven, where he is a pastor.

"Self-love is so critical," he said. "It dictates how we love others."

He recalled a moment several years ago, when he was working at a smaller regional library in Connecticut. A family came in looking for emergency food service providers in the community. Kinney could see that the parents were struggling. He got his director’s approval to reach out to them, because "I knew that they were in need."

In a short time period, the library pulled together temporary support for them.

As he spoke, King’s words—An individual has not started living until he can rise above the narrow confines of his individualistic concerns to the broader concerns of all humanity—stood out in blocky white lettering against a black-and-teal background. The statement is from an August 1957 address that King gave in Montgomery, Alabama. The words rang just as true on a chilly, overcast January day in Connecticut.

“We need to believe in ourselves, and we need to believe that we are somebody,” chimed in Vivian Bordeaux, customer service librarian at the Bridgeport Public Library. “People that love themselves use their energy and their resources to build up others.”

Referencing excerpts from King’s 1947 op-ed “The Purpose of Education,” Browne praised libraries as educational hubs and gathering spaces, often home to community meetings and programming for all ages. As a library technician, she looks to the tools and resources at her disposal as pathways to education.

She acknowledged that libraries are sometimes much more. During her time in Hartford, she watched as a bookmobile from the Hartford Public Library also became a community food pantry, where books arrived with canned goods. She also recalled introducing several Spanish-speaking families to a branch library in Hartford, struggling to remember her own high school Spanish vocabulary in an attempt to make the building as accessible to them as she could.

As a librarian, she said, she sees it as her charge to serve all people from a given community. But she has a soft spot—and an obligation—when it comes to communities of color and to Black families in particular.

“We have to love ourselves and love Black people,” she said.

Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown with Chris "Big Dog" Davis' granddaughter McKenzie at the Stetson Branch in July 2020. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

In New Haven’s Dixwell neighborhood, those words resonated as Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown continued to build a new diaspora-themed collection at the renovated Stetson Branch of the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL). The location is expected to open at the new Dixwell Community Q House later this year. While Brown has held her current role since 2006, she has been advocating for the surrounding community for much longer.

“Part of my role is to provide literature and information so that Black people can have more of an understanding of their culture,” she said. “I’m also a community activist. When people call on me to get involved, I’m called to action. I can use my position to advocate for and see to it that people like me are represented at the table.”

Brown grew up in New Haven, the child of Newhallville matriarch and lifelong neighborhood champion Lillian Brown. She was 11 when King was shot and killed in Memphis. Monday, she recalled returning home that day to see her aunt in tears and her mother ready to tell her daughter “not about who shot him, but why he was shot.”

Brown—who has been vocal in teaching young and adult readers alike about Civil Rights leaders beyond King—said it sparked something deep within her.

That history stayed with her as she marched downtown to watch the Black Panther Trials two years later, then became a mother herself at 17. It stayed with her as she worked under Black City Librarian James Welbourne, who urged her to pursue work in library science and pushed for her professional development. It stayed with her when she became branch manager in 2006, and started ordering books where the protagonists looked like her, and like people in the community. She built out programming for neighborhood kids, from a weekend chess club to West African drum and dance classes.

She called herself an honorary grandmother to three or four generations of kids who have cycled through the library system, and credited Black librarians including Welbourne and librarian-activist E. J. Josey for paving a path that has allowed her to lead. When Welbourne fell ill in 2011, she visited him in the convalescent home where he was staying. She asked him what he needed.

“He said ‘I need you to keep taking care of us,’” she recalled. “That means that you sit at the table professionally and you put us at that table too.”

City Librarian John Jessen, Branch Manager Diane Brown, Artspace New Haven Director Lisa Dent, and Cultural Affairs Director Adriane Jefferson in September 2020. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

Since—and in the midst of a pandemic—she has done just that. Before Covid-19 hit New Haven, Brown transformed Stetson into a mecca for Black literature, after-school and weekend activities, and a place where neighborhood kids could learn about the African diaspora one afternoon and try skateboarding in the parking lot the next. In greater New Haven, Brown jumped into volunteer and board leadership positions, building relationships in the community as she went.

“I feel like I’m somewhat of a gatekeeper of my people in New Haven,” she said. “I don’t know what people think when I sit on these boards, but I’m not a closed mouth. I’m not bought. I’m not sold. I don’t play politics with my people. I use my position as a branch manager to advocate and just use whatever power I have to see to it that my people are taken care of.”

After the NHFPL closed its physical doors in March, she worked on weekly story time and monthly “Africa Is Me” sessions online with dancer Hanan Hameen. In July of last year, the library reopened for curbside pickup and printing assistance. Inside, Brown and her staff have spent the past year “weeding” the collection, a process that has entailed taking 23,000 books out of circulation to make room for thousands of new ones.

Now, thousands of those books have gone to neighborhood kids, parents building home libraries, preschools, and community book banks. Most recently, she and staff assembled 100 bags with books and Civil Rights-themed coloring pages for Women Of The Village, who distribute food each week at the Dixwell Avenue Police Substation. Brown has worked with the group for over a decade.

When the so-dubbed “Stetson 2.0” opens this summer, it will do so with a reimagined collection dedicated to the African diaspora, new technological resources, and a mentorship space for young Black women. Brown said that for years now, a number of women in their 20s and 30s have started referring to her as “mommy” and “auntie.” She’s done her best to nurture every one of them, she said.

“I stay grounded, and I never rise above anybody,” she said. “I’m with my people. People have asked me ‘do you want this position at the main branch? Do you want a position in leadership?’ I feel like I’m where I’m supposed to be right now. I get a lot of love from everybody. But the love that I get from my people especially ... for them to trust me with their lives, with the lives of their children … that’s the biggest reward that I can get.”

Top: Marian Huggins at Mardi Gras in February of last year. Bottom: Luis Chavez-Brummell at the Wilson Branch Library in July 2020. Lucy Gellman File Photos.

That sense of community-oriented work also flows through the Courtland S. Wilson Branch of the NHFPL, said Deputy Director and former Wilson Branch Manager Luis Chavez-Brumell. Located in the city’s Hill neighborhood, the branch has been working for years to grow culturally responsive programming, from language classes in Pashto and Spanish to polyphonic celebrations of Three Kings Day. This year marks its 15th birthday: building the branch was one of Welbourne’s crowning achievements as city librarian.

Chavez-Brumell praised Mitchell Branch Manager Marian Huggins, who until last year worked as the community outreach librarian at Wilson. In her role, Huggins partnered with Project Longevity’s Stacy Spell, the Urban League of Southern Connecticut, and members of Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ) to hold a film screenings around Black history and the breadth of a diaspora.

She started Wilson’s Urban Life Experience book discussion series, which has since migrated to Zoom. Recent selections have included David Chariandy’s novel Brother and Charles Barber’s Citizen Outlaw. She also launched the library’s “Democracy In America” series, a collaboration with Public Humanities at Yale. Last year, she received an award from Project Longevity for her work.

Chavez-Brumell added that he sees history as a living thing; the work that Black librarians do every day is part of that. For instance, he said, his dad was born in 1950. Brown v. Board of Education did not have a ruling from the Supreme Court until four years later. Jump forward to 2021, and he's is helping run a city's library in the midst of the worst pandemic in a century.

He said he still wonders what his grandparents on one side of the family, who were Black and lived in North Carolina, might say if they had lived to see their grandson named deputy director of the NHFPL.

“I think overall in terms of BIPOC librarians, we’re thinking about not only serving as curators, but as creators,” he said in a phone call Monday afternoon. “And we work with the community to go from consumers to creators. How do we show the importance of community, how do we generate books and services that reflect our community, that reflect our humanity?”

He added that he’s been on panels where he’s been asked—often by white librarians—how to build up programming and resources by, for, and about people of color. He and Huggins, as well as City Librarian John Jessen, have done that work at Wilson. Brown is continuing to do so at Stetson. When he hears it, he often reframes the question.

“I tell them, it’s not just about people checking out materials,” he said. “Your job is to prepare the kids for the world. And the world looks a lot more like Hartford and New Haven than other towns.”