Culture & Community | Nu Haven Kapelye | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

| YouTube. |

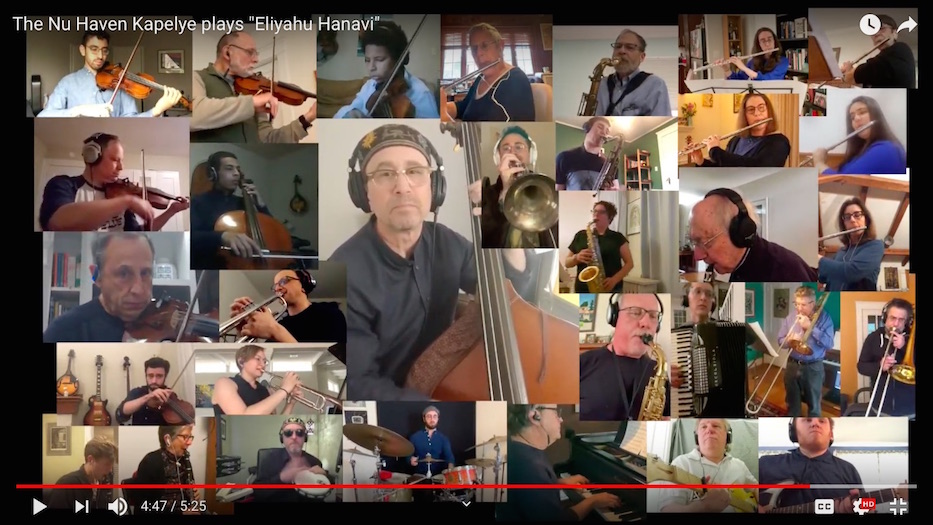

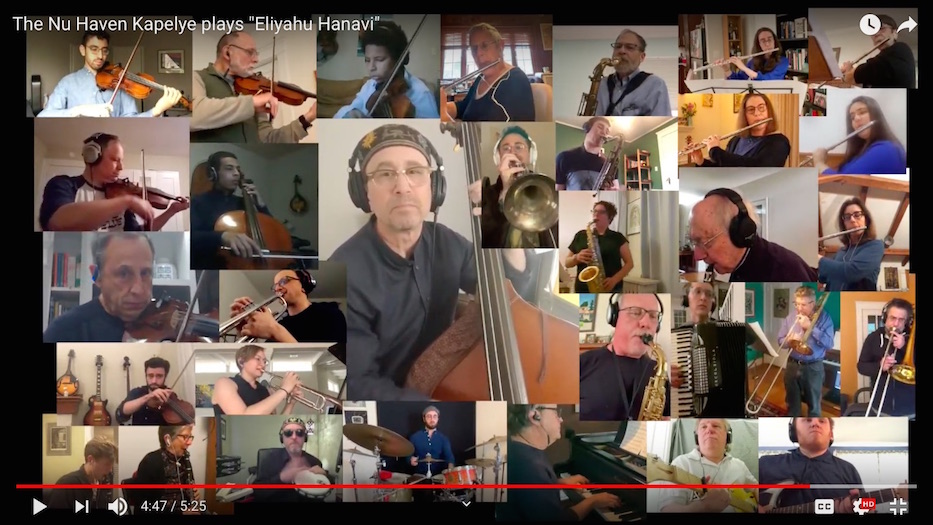

It’s like a magic trick. David Chevan claps his hands once, and four musicians appear on the screen. He claps them again, and suddenly there are 11 of them, each in their own separate box on the screen. He claps a third time, and there is a whole cacophony of palms pressing together, ready to dip into song.

Chevan is the artistic director of the Nu Haven Kapelye, a klezmer and Yiddish music ensemble that plays in New Haven and Hamden. Monday evening, the group released a pre-Passover video of 32 members playing “Eliyahu Hanavi” from their homes, video and audio layered to show all of them on screen together.

“I know this is not an easy time and we could all use a little cheer about now,” Chevan wrote in an email Monday evening. “In this time of social distancing, when we can’t play together we can still make a recording together.”

The song—welcoming Elijah the Prophet—feels right on time for Passover, which begins Wednesday at sundown. As the video opens, Chevan is alone in his home, leaning into his upright bass in blue jeans and skullcap. From all sides of the frame, members appear: horns, percussion, and cello, then flutes and strings.

It’s a fun game of musical hide and seek. Dana Astmann pops up in the corner with an accordion. Flute players bob their heads right on cue with a few down beats. Chevan holds down the center until he disappears, and bandmates cluster in. Eli Jackson takes it away for violin solo just beyond the two minute mark. Almost as soon as he’s disappeared, horns have filled the frame with a brassy backbone.

The project was mastered by Noah Chevan and Jay Miles, both musicians who are isolating in New York and New Haven respectively (Noah is also David's son, and a longtime member of both the group and the Greater New Haven Jewish community). At the beginning of the process, the two instructed musicians to each use the same hand clap so they could sync the audio and the sound.

From New York, Chevan streamlined the audio, a process he called relatively straightforward because he’s used to working on multi-track projects remotely. Musicians sent most of the audio from their iPhones, a mix of which he sent on to Miles once he was happy with it. Over email, he recalled getting excited when he saw Miles’ final cut for the work.

“The production is equal parts slick and lo-fi but 100 percent DIY,” he wrote Monday. “It's homemade, cuz where else would we be right now?"

"Days can be grim living in New York City during quarantine right now, but creative collaboration is keeping me inspired daily,” he added.

Miles then blended the 32 video tracks to sync up with the sound, a process that he described as “completely insane,” but also well worth the hassle. As he was figuring out where to place each musician, he worked to stitch family units back together. He said it was important to him to get the song out before Passover had started, as a message of hope and solidarity to families celebrating apart.

He moved siblings Ari and Elena Kagan, who are in Maryland and San Francisco this year, next to each other for a frame. Then he put Mandi and Max Jackson on either side of Eli Jackson during his solo. They'll be celebrating under the same roof this year—but he said it still felt right.

As the track neared its end, he crammed all 32 musicians onto screen at the same time (“I wanted it to be almost obnoxious,” he joked), to show them playing as they might at one of their real-life concerts on the New Haven Green or Congregation Mishkan Israel. He ended the video on Chevan, “to reiterate this sense of ‘alone, together.’”

“It’s just lovely to feel like we all came together and did this together in a room,” he said in a phone call Tuesday morning. “To be able to put it out there and know that it’s bringing people joy.”

For several of the musicians—if not all of them—the video took on both personal and collective meaning. For the first time in years, Noah Chevan won’t be physically close to his family for a Passover seder, a new reality that Jewish people around the country and the globe are grappling with. He doesn’t think a Zoom seder, on which whole sections of the Jewish community are split, is going to cut it.

“I'm disappointed and upset that I cannot have a seder with my family this Passover,” he wrote in an email Monday. “Not being able to be in the presence of my family removes what I value about the holiday.”

But “one of the ways I express my Jewish identity is through creative outlets like the Kapelye,” he added. “Performing Jewish music with the community connects me to it. I hope people see this video as a community finding ways of coming together in a time when we are unable to physically.”

He’s far from the only one feeling that sense of loss right now. In the thick of a global pandemic, Miles has been worrying about his mother, who is in her late 70s and went into the hospital last week. While some of her early symptoms looked like COVID-19, what she had turned out to be pneumonia. He said the distance has been hard: while he is in Connecticut, she is in Washington, D.C.

He said he’s been waiting for a call that he needs to go down there—but doesn’t even know what protocol looks like when hospital visits have been severely curtailed to limit the spread of coronavirus. After the group released the video on Monday, he sent it straight to her.

“It brightened her day in a way I think we want the video to do for people,” he said. “The point of this was to bring some joy, to brighten people’s lives. To get some positive energy—some toe-tapping—going. To put a little joy out there.”

But, he added, “it’s a goofy holiday this year.” Passover, to its bones, is built on gathering to tell the story of slavery, plague, forced migration and miracles. Typically, it marks a moment to reflect on liberation and community through ritual practices, from throwing out leavened products to ditching iPhones, and screen time for real-life conversation around the exodus story.

Some families and friend groups have held the same prayer books, or Haggadot, for years. Others have reserved specific plates, table settings and recipes for those eight specific days, and seders that usually take place over the first two nights of Passover.

“A holiday that’s meant to be about togetherness and literally overcoming deadly circumstances—what does that look like via a video conference?” he asked aloud. “It’s odd, you know?”

Dana Astmann, whose wife Cynthia did the graphics for the video, echoed that feeling. Typically, the two open their Beaver Hills home to friends for a women’s seder on the first night of Passover, followed by a celebration with family on the second.

This year, both of those rituals have been pushed online. In the midst of it, both have been working from home, and found themselves in near-triage mode for the arts organizations they work for. Instead of trying to normalize Zoom, they’re looking at what they can take from the current moment.

“It’s sad that we can’t actually gather, but at the same time we can still tell the story and we can still find ways to connect with each other,” said Cynthia.

“There are so many new readings that people are creating this year,” Dana chimed in, noting that she's been using the website Haggadot.com for years, and has found it populated with readings that tie into the coronavirus pandemic. “It feels very different, and it also feels very powerful to me."

"This is not a plague visited on us by God," she added. "This is a human made disaster. One of the mitzvot of Passover is finding a new way to tell the story. So relating it to 2020, in my small way, is one of the things I can do.”